Nikola Kožul (photo courtesy of Nikola Kožul)

Nikola was just a few months old when, in August 1995, his family – together with the other 200,000 people of Serbian nationality, left Croatia in a hurry. After living in Serbia for fifteen years, he returned to Croatia where he attended high school and where he still lives and works. We met him

I first met Nikola Kožul at the Peace Studies course organised by the Centar za Mirovne Studije (CMS) in Zagreb. One day, during the module on the wars of the 1990s, this tall, thin 28-year-old took the floor and told his story – that of one of the approximately 200,000 Croatian Serbs who in August 1995 hurriedly left their homes, while the Croatian army advanced to reconquer the Krajina during Operation Storm (Oluja). Between 1995 and 2010, Nikola lived in Serbia, before returning to Croatia, where he attended high school and graduated in law. His speech struck me not only for the drama of the events he reported, but also for the tenacity, commitment, and even optimism that transpired from his words. Today Nikola works as a jurist at the Serbian National Council (SNV, the body representing the Serbian minority in Croatia) and offers free legal assistance to those who need it. On the occasion of Oluja's 28th anniversary, I met him in a café in the Croatian capital to have him tell his story in detail.

Nikola, you were born in Benkovac, in the hinterland of Zadar, four months before Operation Storm. What did your family members tell you about August 1995?

The big question within the Serbian community is: "did we leave on our own or did they kick us out?". The official Croatian version claims that the Serbs decided spontaneously to leave. My parents say that they were afraid, that they didn't trust the new Croatian authorities and that they saw everyone fleeing. They decided at the last moment. On the morning of August 4, 1995, when my mother called my grandfather to say "we have to go, everyone is running away", he was in the fields building a fence for the chickens. Later I heard other stories, of people who had been approached by Serbian security agents who had advised them to leave... It's a story we will never be 100% sure about. I think there was an agreement between Croatia and Serbia, because then, during our trip, the Serbian authorities continually diverted us towards Kosovo, to populate it with Serbs. In any case, as far as my family is concerned, the psychological effect was enough: everyone ran away and therefore they ran away too. So we left with two cars and in Knin we joined the large column of cars and tractors leaving Croatia.

The image of that column of thousands of people, mostly poor and from rural Croatia, has become one of the best-known symbols of the Oluja operation. What did your family do in Benkovac before the war?

My grandfather was the son of partisans and during the Second World War he ended up, together with the whole family, in an Italian prison camp on the island of Meleda (Molat) and then in Naples. Upon his return, he had started school and graduated in Economics in Belgrade, before returning to Benkovac to work as director of the local agricultural cooperative. My grandmother – 14 years younger – had also studied at university, graduating from the Faculty of Tourism in Zadar. In short, both were examples of success of socialist Yugoslavia, coming from peasant families and becoming part of the new elite. My grandfather was a great believer in Yugoslav values and was against nationalism, so when the new Serbian authorities took control of the Krajina in 1991, he lost his job and ended up in prison for a short time, before finding work again as a bank manager until 1995.

Let's go back to your escape in 1995. Where did you go once you reached the column in Knin?

We stopped first in Prijedor and then in Banja Luka. I was a few months old and it was very hot, so people helped us a lot at every stage. Once we arrived in Serbia (where we knew no one), the column of cars was directed towards Kosovo and many roads were closed. But my grandparents managed to obtain permission to reach Vojvodina and I was baptised in Pančevo. A few months later, in 1996, my grandparents bought a house in Temerin, a small village just north of Novi Sad, while I, my older sister, and my parents went to Kosovo. My dad was a journalist and the only job they offered him was there. My aunt, who was studying at the university at the time, also followed us: the entire Knin faculty had in fact been moved to Kosovo. However, my parents didn't like it there (another war was being prepared...) and in 1997 we returned to Temerin, just when my grandparents tried to return to Benkovac.

Your grandparents returned to Croatia two years after the end of the war... how did it go?

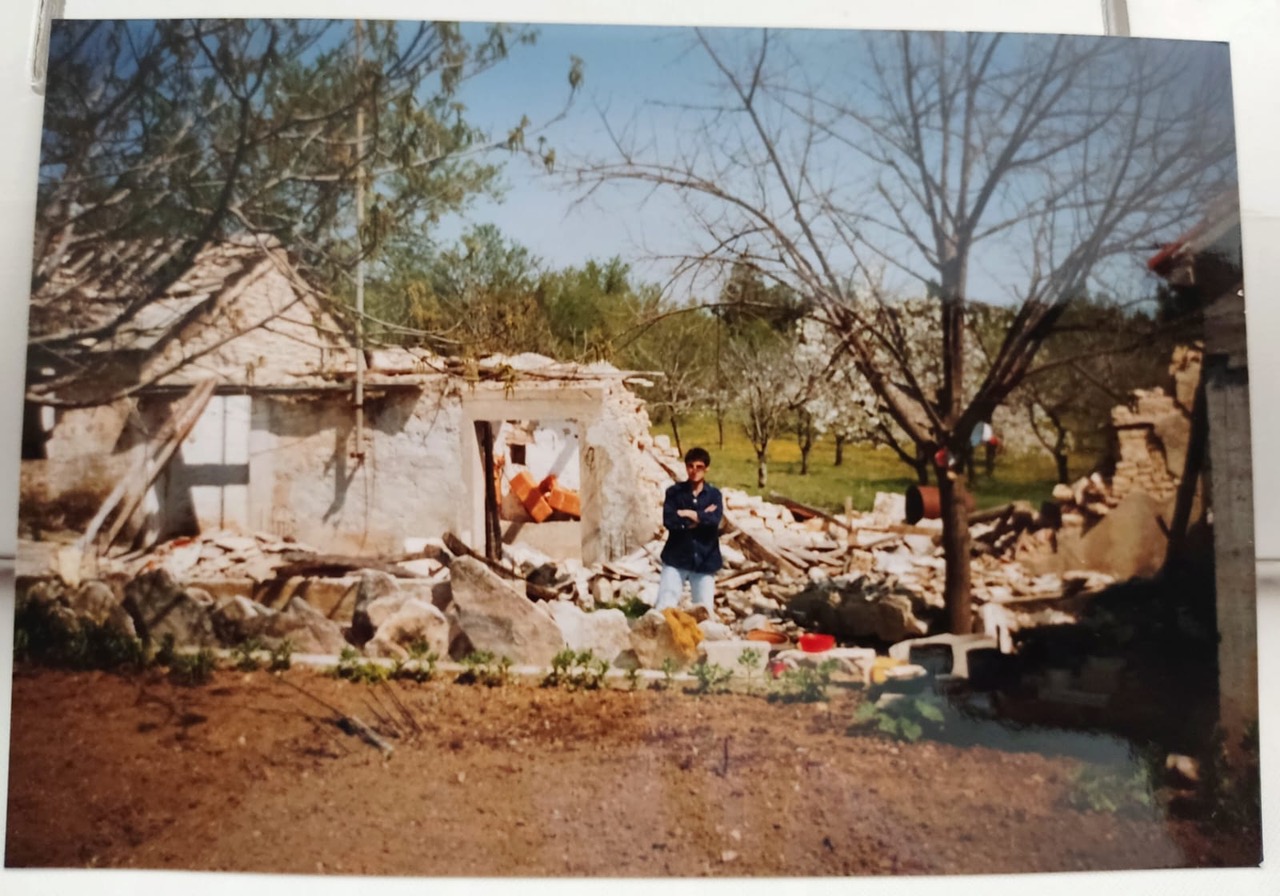

In hindsight, they came back too soon, it was still dangerous at the time. But they couldn't wait any longer. In Benkovac we have countryside: 150 olive trees, two large vineyards, fruit trees… they wanted to take care of it. So they entered Croatia illegally and began to take care of the land, but one day, after they went to visit some family members in Split, they found the house destroyed upon returning. It had been blown up. It was a huge shock for them, but also the moment they decided they would never leave again. They lived in the stable, then rented an apartment in Benkovac and worked in the fields every morning. Even today on the estate, you can see the hole where the family house once stood.

In the meantime you were in Serbia…

Yes. In 1998 my younger sister was born and in 1999 we moved to Nova Pazova, halfway between Novi Sad and Belgrade, where I attended primary school. More than a real city, it is a dwelling that gravitates around Belgrade. I have bad memories of that time, but I often wonder if it's because I only remember the worst or because it really was so difficult. I had friends, but there was no shortage of accidents. To insult me, the children called me "refugee" or "Croatian". Thinking about it now, I understand that those who lived there had spent the nineties in a thousand difficulties and without ever being helped. We, however, had received an apartment and furniture from the Serbian government. There was a lot of envy and anger. Anyway, I never felt at home in Serbia. Even though we spoke the same language, my Croatian accent didn't go unnoticed. “Home” is where you can speak the language you speak at home even outside the home.

In 2000 you returned to Benkovac for the first time. How did it go?

It was winter, during the school holidays. I remember arriving at night, my grandmother telling me "this is your home" and then seeing the house that had been blown up, with stones still scattered in the lawn. That year for the first time I saw the sea, Zadar with its walls, the historic centre... I was enchanted. Compared to the mud of Nova Pazova, it was another world. The following year we returned for the summer holidays and I met the Croatian children. I played with them, but I remember that one day, when I arrived, they were all silent and didn't look at me. One of them told me “we know what you are”. “What?” I asked. “A Serb”, he replied. I learned to relate early to that question: “Who are you and where are you from?”, always so important. In Benkovac, everyone was emerging from the trauma of the war. However, I ended up making friends with those children, we met every summer.

When you finished primary school, you decided to go to high school in Zagreb, while your parents remained in Serbia. How was it?

I followed in the footsteps of my sister, who had already taken that path. My parents didn't see a future for us in Nova Pazova. Education was very important to them, a tool to improve one's condition. The educational offer of the Serbian Orthodox high school in Zagreb was not comparable to that of local schools. It is a sort of an elite school, but open to all. Fully funded by the Serbian Orthodox Church in Croatia, the high school is secular and follows the Croatian national curriculum, allowing children from rural and peripheral areas to study in downtown Zagreb, receiving a scholarship and living in the student's house. When I told my classmates that I was going to Croatia for high school, a girl told me I was a “traitor”. It wasn't easy, much less for my parents who were sending their second child to study in a country that considered them "enemies" after all. But they had little money and could never have offered us an education like the one we received in Zagreb. That high school is really a good thing that the Serbian Orthodox Church has done.

What was it like studying in Zagreb? Did you have new problems with Croatian peers?

As long as we were downtown, no. But when the new high school was built in the Svedi Duh neighbourhood, we found ourselves taking the bus every day with students from one of the worst vocational schools in the city. Every morning they insulted us, threw objects at us, sometimes attacked us. The police often escorted us to school. It was a real problem for the high school. If word had gotten out in the Serbian community, parents would have hesitated to enroll their children and it would have been a real shame, because the school was excellent.

After high school, you chose to study Law in Rijeka. How come?

In my family we always talked about politics, justice, society... These topics interested me and Rijeka is perhaps the most liberal city in Croatia. When I found out that I had been admitted to law school there, I didn't think twice. I stayed in the Kvarner capital for almost eight years, even though I often returned to Zagreb. In fact, I had started with activism, with the political party "Za Grad" [later merged into Možemo, ed.] and then co-founding the Forum for sustainable development "Zeleni Prozor". In those years I participated in various meetings in Brussels, in Kosovo, an Erasmus in Ljubljana... I was able to reinterpret my experience through study and dialogue with young people of other nationalities. I graduated at the end of 2021 and in 2022 I started working at the Serbian National Council (SNV) in Zagreb, not before taking a long bike trip through Italy, which I had been dreaming of for a long time.

Operation Storm still incites the usual divisive rhetoric . How do you read the events of August 1995?

I think there are elements of truth on both sides. In Benkovac there has always been a strong Croatian nationalism, until a few years ago Oluja was celebrated with great fanfare and only in recent years has the situation calmed down a bit. For Croatian nationalists, Oluja remains an error-free and spotless victory. In Serbia, however, people opt for self-victimisation, which feeds Serbian nationalism. We refugees are used and Oluja becomes like NATO bombing. Between these two extreme versions, there is us, the minority, the key to peace. War is always a war against minorities. I think that Krajina was a legitimate part of Croatia and that the Serbian authorities made a mistake in 1991 by expelling the Croats, destroying their houses and churches. In 1995, however, it was Croatian nationalism that made the mistake. I would have liked the Croatia of that time to be more mature and that the authorities in Zagreb had really clearly said "you must not leave", "no civilians will be mistreated". But it didn't go that way. The truth is that – and here it is denied – 200,000 Serbs left, between 600 and 1200 civilians were killed, 20,000 houses were destroyed... And for those who returned, like for my grandparents, it wasn't easy.

What do you see in the future of the Serbian minority in Croatia?

Unfortunately, the pre-war situation cannot be recreated. Those territories will never be as populated as they were before. However, we can improve the situation and in recent years we have been working in this direction. In 2020, the Plenković government invited representatives of the Serbian minority to the commemoration of Oluja in Knin for the first time. For the first time they mentioned the victims, they spoke about justice, they said sorry... The narrative in Serbia, however, does not change, in fact it has become more extreme.

Is the glass half full then?

For me it is, my parents would say no. But perhaps the difference lies in the point of view. They saw the glass completely full before 1991, I started with an empty glass. On the other hand, I am aware that I am a positive example of integration of Serbs in Croatia, perhaps an exception. Not everyone went to Serbian high school in Zagreb. Many remained in rural areas, perhaps they became radicalised with nationalism. Others left for Germany. But if it is true that our villages are increasingly older and emptier from a demographic point of view, it is also true that there are those who return from abroad. A new society will be created. In short, I am optimistic albeit cautiously.

Without help from the state, more than thirty years passed without being able to rebuild that house. But I am sure that we will rebuild our grandparents' house and relaunch agricultural production with the help of European funds. I have already told my parents that I will gladly take care of all administrative matters.