Kiev (2014), demonstration for Ukraine's entry into the EU © Drop of Light / Shutterstock

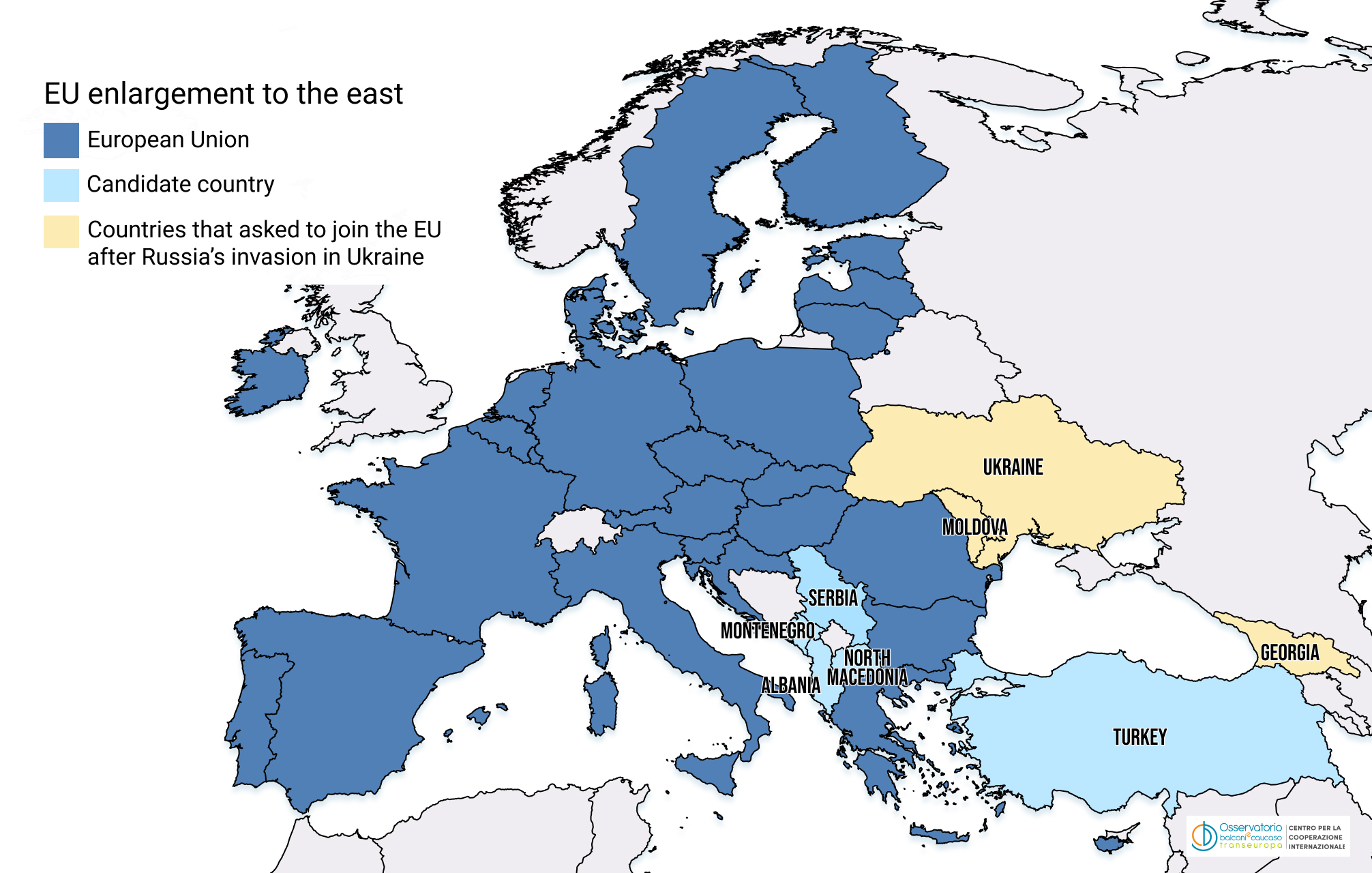

Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova have officially applied to join the European Union. The first reactions have been positive, but it will be a long process: in the meantime, however, the enlargement of the EU could finally get going again, and some novel solutions could be tested

After a decade of crisis, the eastward enlargement of the European Union has suddenly regained space on the European political agenda. After the aggression by Russia, in fact, on February 28, 2022, Ukraine applied for EU membership, followed on March 3 by Georgia and Moldova.

Ukraine's request has already been positively received by the European Parliament, which on March 1 approved by a very large majority a resolution which "invites the institutions of the Union to work to grant Ukraine the status of candidate country for accession to the EU, in line with Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union and on the basis of merit". The EU Council has also declared itself in favour , asking the European Commission to quickly conduct an investigation and then officially express itself on the matter. In the event of a positive opinion, the EU heads of state and government will have to decide whether and how to proceed.

The options on the table

There are actually no concrete possibilities in the near future for Ukraine, Georgia, or Moldova to join the EU, given how the enlargement process currently works. Even in the most optimistic scenario, technical analyses, political negotiations, and the adaptation of national legislation to the myriad of existing European standards would take several years. It is true that these countries have already begun to adapt to a set of EU standards based on the association agreements they signed with the EU in 2014 as part of the Eastern Partnership , but many reforms have yet to be implemented – and in any case they would not be enough, as in order to join the European Union it is also necessary to provide guarantees of political stability which are currently lacking.

For this reason, there are two possible measures that are most talked about. The EU could grant candidate country status to Ukraine and possibly to the other two countries that have requested it. This would be a preliminary step with an exclusively political value, which would not necessarily lead to the opening of accession negotiations – but its political value would be difficult to deny. In this regard, various analysts have noted that a possible enlargement of the EU towards the east could represent an even greater political defeat for Putin's Russia than a possible enlargement of NATO.

Alongside the granting of candidate country status, the EU could offer Ukraine, Georgia, or Moldova some unprecedented opportunities in terms of access to the single market – as also suggested by the European Parliament and the President of the European Commission Ursula von Der Leyen. Further facilitations for the movement of people across borders could possibly also be envisaged.

Warm and lukewarm support

While the European Parliament has yet to express itself on the applications of Georgia and Moldova, most of its members have already said they are in favour of Ukraine's future integration into the European Union. Addressing the highest Ukrainian authorities, President of the Parliament Roberta Metsola stated : "We recognise a European perspective for Ukraine and […] we welcome your candidacy, we will work to achieve this goal".

The only voices that stood out were those of the Left group in the European Parliament and some exponents of the far-right group Identity and Democracy, who asked to evaluate Ukraine's request only after the cessation of hostilities in the country.

The popular and liberals, on the other hand, showed particular enthusiasm for the enlargement of the EU to Ukraine, as did a number of MEPs from Central and Eastern Europe – including the chairman of the European Parliament delegation for Ukraine, Witold Waszczykowski. Some of his colleagues from the Polish conservative PiS party pledged to "do our best to recognise [Ukraine] candidate country status as soon as possible, based on new rules for membership". Central-Eastern Europe spoke almost unanimously in favour of a possible enlargement of the EU towards the east. The president of the European Commission declared that Ukraine is "one of us and we want it in the European Union".

Other governments have so far been much more cautious, particularly France – for a long time very sceptical about the entry of new countries into the EU. The president of the European Council Charles Michel pointed out that enlargement is "a delicate issue" on which governments have "different views and sensibilities". The differences concern both the tactical opportunity to commit to enlargement in the current phase of conflict with Russia, and the strategic opportunity to proceed with further enlargements in the absence of a broader restructuring of the EU.

Options and scenarios

The war in Ukraine is opening up spaces for a broader reflection on relations between the EU and the neighbouring countries, starting with the Western Balkans. If progress were actually made with eastward enlargement, the process involving the Balkan countries could also resume: it would be unthinkable to admit Ukraine to the EU while still excluding the countries of the region that have started the process much earlier.

In addition to the number of states to be admitted and the timing of possible enlargement, the new debate could lead to a more comprehensive rethinking of some policies, mechanisms, and structures of the European Union. The redefinition of the forms of collaboration between member states in the field of defence has already begun, but a more general review of the common foreign and security policy, including neighbourhood policy, will be needed.

The war in Ukraine and the new requests for membership of the European Union could lead to the realisation of some other reasoning that has been in the air for some time, in particular with regard to a multi-speed Europe and compliance with European standards. To date, the EU has reserved most of its opportunities only for member states, and thanks to the promises of membership it has managed to promote incisive reforms in the candidate countries. Once a country has joined, the EU has a harder time ensuring compliance with shared rules – this is why there is a need to introduce so many reforms and guarantees before accession.

Among the solutions, it is likely that lighter forms of integration will be proposed, which may precede or complement the long process of joining the EU, quickly granting the countries concerned a series of opportunities hitherto reserved only for member states. Or one could imagine streamlining and accelerating the standard accession procedure, but combining it with a series of new tools to then continue to bring member states closer to – and bind – to shared political and economic standards.

The action is co-financed by the European Union in the frame of the European Parliament (EP)'s grant programme in the field of communication. The EP is, in no case, responsible for or bound by the information or opinions expressed in the context of this action. The contents are the sole responsibility of OBC Transeuropa and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Go to the project’s page: “The Parliament of rights 3”.

To Top

To Top