Georgia’s Syria Problem

Up to 100 Georgian citizens, mostly from the Pankisi Valley, have allegedly left their homes to join the Islamic State in Syria. With no effective counter-radicalisation policies, the situation could become even worse

On 14 October, Jainuladebin Hakikji, a 36-year-old Indian citizen, did not receive the customary Georgian welcome when he arrived at Tbilisi’s International Airport on a flight from Dubai. Instead, the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper reported, while his clean-shaven colleague was allowed to enter the country, Hakikji was not. A Moslem by religion, the chartered accountant resident in the United Arab Emirates alleges that Georgian border control singled him out because of his beard.

The document issued by the Georgian Border Police listed the reasons why travellers can be barred from entering the country. However, none of the boxes, which dealt with standard issues such as lack of funds or not being in possession of the necessary travel documents, were ticked.

“While waiting for the flight back, there was an officer assigned to watch me,” he was quoted by Gulf News as saying. “‘I wanted to go to the washroom but he said I was not allowed. They treated me as if I was a criminal. They said they couldn’t let me in for security reasons, but they did not let me in because of my appearance. I am a Muslim and I follow the religion strictly, which is why I have a long beard.”

Hakikji’s experience comes as Georgia continues to tighten its border control, as per last year’s UN Security Council Resolution 2178, to prevent travel to Syria by those seeking to join the Islamic State — also known as ISIS, ISIL, and Daesh — or al Qaida affiliated groups. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation and Europe (OSCE) and U.S. State Department both consider Georgia to be a transit route for Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) from the North Caucasus and Central Asia.

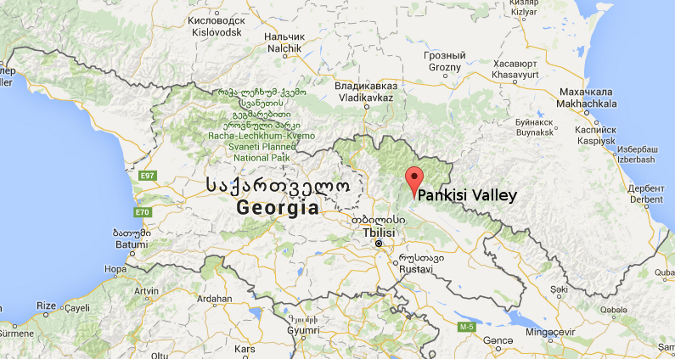

Militants from the Pankisi Gorge

Tarkhan Batirashvili, aka Abu Omar al-Shishani, hails from Georgia’s picturesque Pankisi Gorge and, as a veteran of the August 2008 war with Russia, is a prominent military commander for ISIS. To date, at least 13 residents of Pankisi are believed to have died fighting in Syria.

Indeed, Georgia is also a source of new recruits, with as many as 100 believed to have left the country for Syria. Many are believed to hail from Pankisi. With Georgian citizens able to enter Turkey without visas and even solely on their identity cards, it has been relatively easy for anyone wishing to join ISIS to find their way to Syria. In April, two teenagers, 16-year-old Muslim Kushtanashvili and 18-year-old Ramzan Bagakashvili, did just that.

Traditionally Sufi, many young ethnic Kists living in Pankisi are increasingly attracted to Salafism. Moreover, NGOs also report that some ethnic Azeris, ostensibly Shia rather than Sunni, are also converting. One possible reason for this is that many ethnic Azeris, as well as citizens of neighbouring Azerbaijan, are non-sectarian in their understanding of Islam. In Azerbaijan, the head of the Caucasus Board of Moslems is Shia while his deputy is Sunni.

In the ethnic Azeri-inhabited Georgian village of Karajala, for example, two women in their late twenties, Elmira Suleymanova and Diana Gharibova, left for Turkey in order to follow their husbands to Syria. According to media reports, neither could be considered as living in poverty, the general reason that the Georgian government and some others argue is responsible for the problem. In reality, however, the reasons for radicalisation are many as well as diverse.

In May, legislation made joining an illegal armed group and travelling abroad to participate in terrorism a criminal offence punishable by up to nine years in prison. However, despite the focus elsewhere on counter-radicalisation policies aiming to combat the ideological appeal of groups such as ISIS, no such programmes currently exist in Georgia. The need for Countering Violent Extremism, or CVE as it is more commonly known, is also highlighted in UN Security Council Resolution 2178.

In particular, effective CVE requires the involvement of community and religious leaders, local civil society, women, youth, and credible messengers such as the victims of terrorism and disillusioned former fighters to counter the single narratives of extremist groups such as ISIS.

Explaining radicalisation

“A lack of opportunities for formal Islamic education, fragmented Muslim institutions, and a lack of local civil society measures have created strong inroads for more conservative iterations of Islam, including Salafi Islam, to create a substantial ideological presence,” says Wake Forest University researcher Bennett Clifford. “Local community-driven, bottom-up programs are preferable to large, organised governmental CVE strategies.”

If counter-radicalisation programs

are intended only for Muslims,

a perception of being “singled out”

and receiving unfair treatment can arise

Bennett Clifford

Clifford researched the situation in Pankisi and also Adjara and Kvemo Kartli earlier this year. “Economics are a necessary but insufficient factor to explain radicalisation,” he concludes. And with adherents of the Georgian Orthodox Church responsible for discriminatory and sometimes extremist behaviour towards Moslem citizens in Adjara, there is the danger that marginalisation in predominantly Christian Georgia could further fuel Islamic radicalisation.

“If counter-radicalisation programs are intended only for Muslims,” says Clifford, “a perception of being “singled out” and receiving unfair treatment can arise.”

But with Russia now militarily engaged in Syria, narratives from ISIS and other groups fighting Assad are likely to prove even more appealing, especially in a community such as Pankisi which is also home to refugees from the Chechen wars of the 1990s and 2000s. The situation is made even more problematic by the almost complete lack of counter-narratives to combat extremist propaganda readily accessible on the Internet.

In June, Tbilisi-based journalist Helena Bedwell quoted just one example of how prevalent that is.“The religion of Pankisi is Islam,” a submission to a local news blog by a student in Pankisi read. “Muslims go to do Jihad. Nowadays, Jihad is in Syria. Teenagers from Pankisi go to Syria to do Jihad. They think that it is the right way. A lot of teenagers died in Syria for Allah. They think that when they die in Jihad they will go to heaven. They fight against Assad soldiers. The mojahids are from all over the world, including from Pankisi.”

*Onnik James Krikorian is a speaker and participant in expert working group meetings, seminars, and conferences on Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) and Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTF) organised by the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC), Global Counterterrorism Forum (GCTF), Hedayah Center, International Center for Counterterrorism — The Hague (ICCT), the OSCE office in Tajikistan, the OSCE Transnational Threats Department, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Georgia’s Syria Problem

Up to 100 Georgian citizens, mostly from the Pankisi Valley, have allegedly left their homes to join the Islamic State in Syria. With no effective counter-radicalisation policies, the situation could become even worse

On 14 October, Jainuladebin Hakikji, a 36-year-old Indian citizen, did not receive the customary Georgian welcome when he arrived at Tbilisi’s International Airport on a flight from Dubai. Instead, the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper reported, while his clean-shaven colleague was allowed to enter the country, Hakikji was not. A Moslem by religion, the chartered accountant resident in the United Arab Emirates alleges that Georgian border control singled him out because of his beard.

The document issued by the Georgian Border Police listed the reasons why travellers can be barred from entering the country. However, none of the boxes, which dealt with standard issues such as lack of funds or not being in possession of the necessary travel documents, were ticked.

“While waiting for the flight back, there was an officer assigned to watch me,” he was quoted by Gulf News as saying. “‘I wanted to go to the washroom but he said I was not allowed. They treated me as if I was a criminal. They said they couldn’t let me in for security reasons, but they did not let me in because of my appearance. I am a Muslim and I follow the religion strictly, which is why I have a long beard.”

Hakikji’s experience comes as Georgia continues to tighten its border control, as per last year’s UN Security Council Resolution 2178, to prevent travel to Syria by those seeking to join the Islamic State — also known as ISIS, ISIL, and Daesh — or al Qaida affiliated groups. The Organisation for Security and Cooperation and Europe (OSCE) and U.S. State Department both consider Georgia to be a transit route for Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) from the North Caucasus and Central Asia.

Militants from the Pankisi Gorge

Tarkhan Batirashvili, aka Abu Omar al-Shishani, hails from Georgia’s picturesque Pankisi Gorge and, as a veteran of the August 2008 war with Russia, is a prominent military commander for ISIS. To date, at least 13 residents of Pankisi are believed to have died fighting in Syria.

Indeed, Georgia is also a source of new recruits, with as many as 100 believed to have left the country for Syria. Many are believed to hail from Pankisi. With Georgian citizens able to enter Turkey without visas and even solely on their identity cards, it has been relatively easy for anyone wishing to join ISIS to find their way to Syria. In April, two teenagers, 16-year-old Muslim Kushtanashvili and 18-year-old Ramzan Bagakashvili, did just that.

Traditionally Sufi, many young ethnic Kists living in Pankisi are increasingly attracted to Salafism. Moreover, NGOs also report that some ethnic Azeris, ostensibly Shia rather than Sunni, are also converting. One possible reason for this is that many ethnic Azeris, as well as citizens of neighbouring Azerbaijan, are non-sectarian in their understanding of Islam. In Azerbaijan, the head of the Caucasus Board of Moslems is Shia while his deputy is Sunni.

In the ethnic Azeri-inhabited Georgian village of Karajala, for example, two women in their late twenties, Elmira Suleymanova and Diana Gharibova, left for Turkey in order to follow their husbands to Syria. According to media reports, neither could be considered as living in poverty, the general reason that the Georgian government and some others argue is responsible for the problem. In reality, however, the reasons for radicalisation are many as well as diverse.

In May, legislation made joining an illegal armed group and travelling abroad to participate in terrorism a criminal offence punishable by up to nine years in prison. However, despite the focus elsewhere on counter-radicalisation policies aiming to combat the ideological appeal of groups such as ISIS, no such programmes currently exist in Georgia. The need for Countering Violent Extremism, or CVE as it is more commonly known, is also highlighted in UN Security Council Resolution 2178.

In particular, effective CVE requires the involvement of community and religious leaders, local civil society, women, youth, and credible messengers such as the victims of terrorism and disillusioned former fighters to counter the single narratives of extremist groups such as ISIS.

Explaining radicalisation

“A lack of opportunities for formal Islamic education, fragmented Muslim institutions, and a lack of local civil society measures have created strong inroads for more conservative iterations of Islam, including Salafi Islam, to create a substantial ideological presence,” says Wake Forest University researcher Bennett Clifford. “Local community-driven, bottom-up programs are preferable to large, organised governmental CVE strategies.”

If counter-radicalisation programs

are intended only for Muslims,

a perception of being “singled out”

and receiving unfair treatment can arise

Bennett Clifford

Clifford researched the situation in Pankisi and also Adjara and Kvemo Kartli earlier this year. “Economics are a necessary but insufficient factor to explain radicalisation,” he concludes. And with adherents of the Georgian Orthodox Church responsible for discriminatory and sometimes extremist behaviour towards Moslem citizens in Adjara, there is the danger that marginalisation in predominantly Christian Georgia could further fuel Islamic radicalisation.

“If counter-radicalisation programs are intended only for Muslims,” says Clifford, “a perception of being “singled out” and receiving unfair treatment can arise.”

But with Russia now militarily engaged in Syria, narratives from ISIS and other groups fighting Assad are likely to prove even more appealing, especially in a community such as Pankisi which is also home to refugees from the Chechen wars of the 1990s and 2000s. The situation is made even more problematic by the almost complete lack of counter-narratives to combat extremist propaganda readily accessible on the Internet.

In June, Tbilisi-based journalist Helena Bedwell quoted just one example of how prevalent that is.“The religion of Pankisi is Islam,” a submission to a local news blog by a student in Pankisi read. “Muslims go to do Jihad. Nowadays, Jihad is in Syria. Teenagers from Pankisi go to Syria to do Jihad. They think that it is the right way. A lot of teenagers died in Syria for Allah. They think that when they die in Jihad they will go to heaven. They fight against Assad soldiers. The mojahids are from all over the world, including from Pankisi.”

*Onnik James Krikorian is a speaker and participant in expert working group meetings, seminars, and conferences on Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) and Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTF) organised by the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC), Global Counterterrorism Forum (GCTF), Hedayah Center, International Center for Counterterrorism — The Hague (ICCT), the OSCE office in Tajikistan, the OSCE Transnational Threats Department, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).