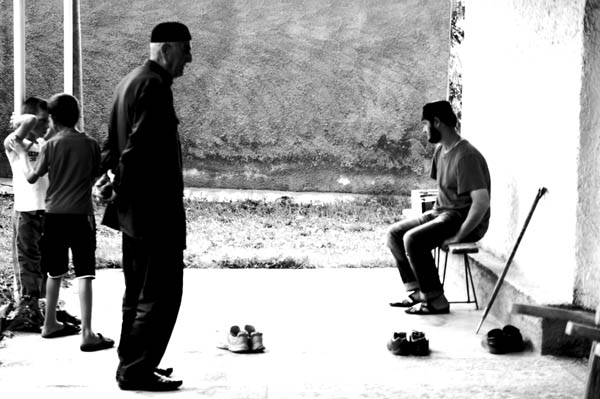

Pankisi valley - photo Matteo Zola

A journey to Duisi, the principal village in the valley of Pankisi in north-eastern Georgia where many of its children have rebuffed the traditions of the fathers. Report

(This is the second of two articles dedicated to the valley of Pankisi, written following the authors' journey through north-eastern Georgia. The first part is available in Italian, here.)

As we enter the Pankisi valley the taxi driver switches off the radio - “Music is not allowed here, the fundamentalists don't want it”. A trench of silence runs along the fields, an armed silence. The small villages inhabited by the kist community are scattered beside mud roads, an occasional figure slides past the walls. No one talks to us; often, for shyness or diffidence, not even a greeting.

In the village of Duisi, the biggest in the valley, it's time for prayer. Above the tin roofs rises an old, rustic and mute minaret, the one of the old mosque frequented by the few still faithful to the sufi doctrine. The call, raucous and metallic, comes from the new mosque with its slim, clean minaret, dotted with megaphones, shading the Mercedes parked at the entrance. “They belong to the preachers”, we are told, “funded by Arabia”, to spread wahhabism and induce young people to fight in Syria.

A process of “Arabization”

Khaso Khangoshvili, head of the council of the elderly of Pankisi, states it clearly: “Now just about all the kist community in Pankisi follows wahhabism. We are victims of a process of Arabization much more dangerous than the previous attempts at forced Russianization, because the Russians tried to annihilate our culture, eliminate our language and even deport us, but for us they always represented something external, which we could resist”. Not so for the Islamic extremism “based on our own religion and which arrived in the valley with the Chechen brotherhood during the war with the Russians in the 90s”.

Fundamentalism is like a cancer in metastasis, as Khaso Khangoshvili well knows, which is why, as far as his age will permit, he is running a minute, sparsely furnished ethnographic museum – a few cooking tools on the wall, some yellowing photos and traditional costumes – a meagre memento of his people. This is also why he has collected and written the Adat, the “code of honour” of the kist, that is a compilation of the norms, precepts and traditions of this dying community.

“The young no longer follow our tradition, nor do they recognize the authority of the council of elders, and that is how our culture will disappear”. What attract the young are precisely those Mercedes parked outside the mosque, gleaming in a land of mud and dust. They are the promises of prosperity from fanatics who preach austerity and strictness, the bigots who prohibit music and parties but at the same time show off their wealth with luxury cars and plasma televisions, when a normal family lives on less than a hundred Euro a month. In the two months preceding our arrival three wahhabi imam were arrested by the Georgian authorities accused of international terrorism and recruiting.

Waiters in Tbilisi

“Here there's no work” Selina tells us, “and our children see the world on internet and television – they know how it is and no longer accept being destined for a shepherd. That's why they join up.” This lady, with a head scarf and appearance of a peasant, teaches English to the children. “Women are not usually allowed to work, but as I'm a widow I'm permitted”. Teaching is however one of the few jobs allowed - “because we work with children, not adults and certainly not men”.

“When my husband died, the people of the KRDF taught me English so I could teach in their centres”. The KRDF is a local non governmental organization which receives funds from UNHCR and its centre in Pankisi is a meeting place for women and children. It's easier to talk here: “Women are not badly off, we're free” they say, but we learn that “those” - pointing with their chin to the wahhabite mosque - “do not let their women go out and also want to prohibit the dhikr”, the traditional Sufi ritual which the village women practise every Friday. The truth is that women in Pankisi live in a subservient condition, endorsed by tradition, but aggravated by the presence of the fundamentalists. “Usually we get married young and even have ten children” they say, half proud and half resigned. “Is it like this in Italy too?”

Marriages in the valley take place at fifteen or sixteen years of age, despite Georgian laws forbidding marriage under eighteen. But, in Pankisi, Georgian law is not always respected. The law of the fundamentalists is what counts. The wahhabi imam Abdurrahman Pareulidze says so clearly: “Religious marriage foresees no age limit” and accuses the council of elders, which refuses to recognize the validity of infant marriages, of “insulting Islam and the Koran”. This is a serious accusation in those parts where adulthood arrives early, especially for girls who are forced to get married very young.

For this reason too the KRDF centre addresses the young, seeming to be a kind of secular youth club, a space offering freedom from the oppressive climate in the family. “I also have two small children” Selina says, “and I hope that learning English they can have a better life, as waiters in Tbilisi”. Waiters in Tbilisi. That is the better future the youth of the valley can hope for.

Wahhabis, never heard of them

“Just last week a boy from Omalo left for Syria”, another woman explains to us. “I know the family, it was a trauma. The boys leave stealthily, because their families don't want them to”. How do they leave? “The journey to Syria is costly, someone must be financing them, but we don't know who”. Perhaps they really don't know, but in such a small community, where everyone knows each other, usually it's the law of silence which wins.

Some names are well known, including Ahmed Chatayev “the maimed”, hero of the Chechen war where he lost an arm following torture by the Russian army. Having left Pankisi for Syria in 2015, he was considered the brain behind the attack on Istanbul airport last June. Another one is Murad Margoshvili, known as Muslim al-Shishani, kist from Duisi, leader of the group Junud al-Sham, affiliated to al-Nusra.

“There are no fundamentalists here, we are all muslims, all brothers” says Razman, of the blue eyes and sly glance. He is used to dealing with westerners in Pankisi who come looking for monsters to slap on the front page. Thus the boundary between culpable silence and self-defence fades. “I've never heard of wahhabis” he concludes.

In the name of the father

The cemetery at Birkiani is one of the places where one can see the tombs of those who have chosen the path of war, the jihad, against the Russians and “the West”. The number of kist guerillas who fell in the Chechen wars or in Syria is unknown. The bodies are buried elsewhere, far from the valley. Often the families do not know what fate befell their loved ones. Among these is Abu Omar al-Shishani, a leader of ISIS, born in Birkiani and who died – according to an ISIS declaration – last July.

His father, Teimuraz Batirashvili, still lives in Pankisi and heard the news of the decease of his son on television. Once called Tarkhan, this son was a child shepherd then Georgian soldier who distinguished himself in the 2008 war against the Russians: a son to be proud of until he changed his name and chose the path of mujahideen “to fulfil the Jihad on the Way to God”.

But is that man with the long beard and kalashnikov on his back still Tarkhan? The old man doesn't answer and closes the door hurriedly, tired of journalists and stupid questions, tired of reviving the pain. Because in the name of a son is his origin, the place he comes from, and the faith, a God for whom to die. But in the name of the son there is also an absence, a wrench from his blood, because in the name Abu Omar al-Shishani, there's no trace of the father: al-Shishani literally means “the Chechen”, a common epithet among many of the Caucasian guerillas who joined the ranks of ISIS, while Abu Omar refers to one of the first caliphs of Islam.

Who chooses the path of jihad leaves everything, right from the choice of name, that is giving up one's surname and that symbolizes rejection of the father's culture. A rejection which, as it has been seen, is becoming more and more widespread in the Pankisi valley and bears witness to the laceration of the community, its affections and its families. If the fatherland is the land of the fathers to be returned to, today Pankisi is no one's fatherland, but the land of sons who have chosen to be orphans. What was the fault of the fathers? “Believing in the past”, declares the imam of the traditional mosque, referring to the traditions the kist have always been tied to. But this answer is not sufficient if we think of the case of Omar al-Shishani, son of an Orthodox Georgian. Evidently fundamentalism takes a hold even on those in this region who were not born Muslim. The reasons for its spreading, therefore, are not to be found only inside Islam.

Fundamentalism at work

Pankisi is a place where it's possible to see Islamic fundamentalism at work, captured in the moment when it is operating in the local community, transforming that community and irredeemably marking its destiny.

It builds its success in a systematic way, community by community, valley after valley, a step at a time.

In the case of Pankisi, isolation and poverty, lack of a future and unemployment are the primary reasons for wahhabism. On the way back from our journey, we can't help wondering how many Pankisi valleys there are in the world.

To Top

To Top