A researcher of ours – now at the University of Dublin – tells about two times when OBC made a difference

A few years ago, one afternoon, I happened to receive an unexpected phone call. It was a Chechen journalist. She told me about the story of a man, recently arrested in Italy and ready to be deported to Russia. In short, as later established by the judiciary, the man had been wrongly refused asylum. The story was characterized by several anomalies involving the man's detention, the manner and timing his application for refugee status was assessed, and his expulsion. It was a complex story, which at the time I told in detail to OBC with a piece that concluded:

"This article tells the story of a man who had a right and who saw it recognised by the institutions. It should be a simple story, but unfortunately it isn't. It seems to have been possible only thanks to the help which, through a series of coincidences, that man had from competent people and organizations dedicated to the case; they enabled him to have adequate legal assistance and put before an attentive judge material which demonstrated the risk which awaited him in his country of origin".

That series of "coincidences" in all probability would not have been possible were it not for the existence of OBC. If not for OBC, probably the journalist would not have known who to call in Italy. When I got the call, the person who was sitting in front of me in the office immediately suggested to call an NGO that dealt with refugees (the Italian Consortium for Solidarity, ICS - Refugee Office ), which they had been in contact with because of previous experiences in the Balkans. The ICS Refugee Office took steps to find legal assistance and through other contacts in Russia I was able to gather additional information necessary to prepare the case and the materials useful to the case. Following this work, the competent court deemed the decision "illegal for insufficient and contradictory reasons and for misrepresentation and omission of consistent evaluation of the same and for violation of the law".

All this was possible thanks to OBC. A place where people with area expertise, language skills (in this case, Russian was essential), and live contacts with Italian civil society stand side by side. And maybe not even that would have been enough if OBC had not used a network of stable contacts with the world of journalism to give resonance to the story. But OBC, fortunately, is also journalism.

In Georgia, something has changed

In November 2013, Georgia and Moldova signed in Vilnius an Association Agreement with the European Union. On that occasion, Ukraine was supposed to sign too. Then things went differently. There has been and still is a lot of talk about the Association Agreement, highlighting its importance as a key element of the path of reforms which the neighborhood countries are going to take. Only few, however, actually read those documents to understand what they really aim to reform and what the content of those hundreds of pages implies beyond the rules in favor of free markets and general commitments to democratic reforms.

Analyzing the agreements and in particular the differences between the EU-Georgia and the EU-Moldova agreements, I discovered something interesting and at the same time worrying: the agreement with Georgia (unlike the one with Moldova) did not contain a section on children's rights, despite the European Parliament's explicit recommendation with its own resolution of "the inclusion in the Agreement of a section dedicated to the protection of children's rights".

The fact that negotiators had decided to ignore, without explanation, a request of the only EU institution directly elected by the people got one thinking. But beyond this, in practice, the absence of this section from the main document that governs the relationship between the EU and Georgia for the coming years meant that children's rights would not be a priority area of cooperation. And then, in all probability, less resources by the EU and less importance given to the issue by the government in Tbilisi.

I discussed the issue with the heads of ChildPact , a regional coalition that deals with children's rights, which in turn interacted with its partners. The Georgian national coalition that unites NGOs dealing with children's rights in Georgia then published a press release on the issue, and I wrote for the first time about it on OBC. After a few months, a few days before the negotiations that were to determine the document's implementation of the agreements, I wrote something again, with the secretary general of ChildPact. The article was published by OBC, in conjunction with a Polish site that deals with the countries of the Eastern neighborhood and a Georgian news site, and the issue was again promoted in the region and Brussels.

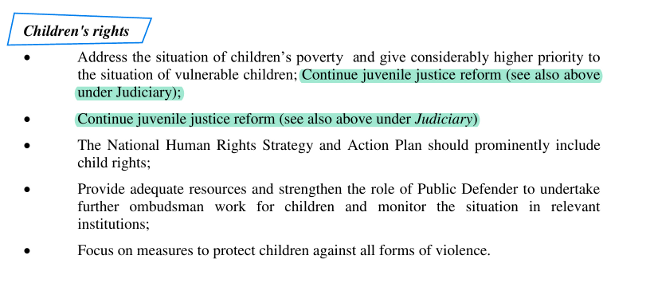

A few weeks later the Association Agenda was made finally made public, a 30-page document that lays out the implementation of the Association Agreement (a document of nearly 1,000). There was no reason to expect anything new. But, at the end of the part devoted to the priorities in the context of political dialogue and reform, a new section was introduced called "children's rights", which included specific requests to the Georgian government to give priority and devote resources to the sector.

I cannot know for sure, but I think this change was due to the articles published by OBC, the press releases that they generated, and the attention raised on the matter. I am convinced of this because the "news" came from us (no one had written about it before); because there were important actors involved; because the section on children's rights was included in a document that was to be only the implementation of the much longer Agreements Association (which did not mention the topic); because it was included as the last item in the section on political reforms; and, finally, because the section on children contains a repeatition (see image), a really unusual typo for EU documents routinely reviewed dozens, if not hundreds of times. I think it likely, or at least plausible that someone raised the issue of children's rights in the negotiations that preceded the final draft of the document, and at that point no one was able to pull back.

All this would not have been possible without OBC. OBC created the conditions for someone to have the time and skills necessary to analyze the Association Agreements (the main document that regulates the relations of the EU with the signatory countries) and for that someone to have contacts with civil society actors in the region and with other organizations that make information online. Without OBC, perhaps that document today would be different, and there would be fewer resources and political pressure to support reforms in favor of children's rights in Georgia.

One of the ways democracy works

Obviously, it's not all about OBC. We needed the ICS Refugees Office, and a careful judge, ChildPact, and coalitions active in the region. And certainly, much more. But without OBC, maybe things would have been different.

These are things that should have happened anyway. That man, according to law, had the right not to be deported to Russia and to obtain refugee status. And the EU-Georgia negotiators had the duty to include children's rights in the agreements, if only because the European Parliament requested it.

But things do not always go as they should. In democracy, control over institutions also comes through quality journalism and civil society. If OBC – a meeting point between these realities – closes, the skills and networks of contacts that were at the core of its existence will inevitably fade away. And many small things could end up going differently.