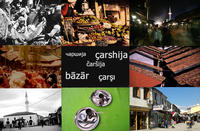

Peja/Peć - foto di Marjola Rukaj

In Peja/Peć, a small town in Western Kosovo, little or nothing is left of the traditional bazaar, mainly because of the 1999 conflict. Although the authorities have faith in its development for tourism, it seems unlikely this will happen

Little is left of the čaršija * in Peja/Peć, a town in Western Kosovo. According to historians it was one of the most important in Kosovo since this was the principal town of the Dukagjin region. A place which linked town dwellers and mountain people, Serbs and Albanians, Roma and Ashkali, it is now a commercial district little different from any other. Just the odd building from the early 20th century, introduced into the çarshija in the time of the first Yugoslavia, still retains some pieces of history; the rest is new, built or rebuilt recently.

From the activities in the past the only ones to survive are some blacksmiths and dressmakers who make traditional costumes which in this area are mostly used at weddings. Peja/Peć was historically famous for its textile manufacturing, but now the quality and variety leave much to be desired. There remains also one single shajak, craftsman, whose material is used to make the traditional Albanian hats, but whose work diminishes daily. “As people become modern nobody wears the plis any more and the old are dying”. Otherwise the çarshija is the place to buy cheap merchandise coming from Turkey and China.

After the rain

The shopkeepers in the čaršija are all Albanian. Despite Peja/Peć having been one of the towns with the greatest number of Serbs in Kosovo, no indication of this remains here, apart from the bilingual road signs internationally required for political correctness.

The Serbs are, however, a constant presence in the çarshija, continually mentioned by the traders, the customers and passers-by, particularly when they speak of the history of the place and its present misfortune. In 1999, when the Albanians were forced to abandon the town to seek refuge in Albania or Macedonia, the Serbs – here always referred to with the derogatory shkja (a term traceable to the word “slave”) – burnt down everything. The čaršija was badly damaged, only Serbian shops surviving, and then the UÇK soldiers, as stated by the Peja/Peć inhabitants themselves, destroyed what was left by the fire.

Rebuilding after the war was spontaneous and random, with architectural criteria the last of worries. At intervals between the new constructions stand some burnt, decrepit and abandoned old buildings. These belong to Serbs who have left and will probably never return.

The relevant authorities say there is no problem: “The shkja are around, they come shopping every morning, undisturbed. We know them. No-one touches them. If they want they can come back, no-one will stop them.” On the contrary, for the traders in the çarshija it seems the Serbs are anything but welcome.

“How can they come back? How dare they, after all they did?” says a shajak worker. This topic being of interest, several passers-by pause to join in the conversation. Their opinions are similar: “They were the ones who set fire to the shops. They had been our friends, our colleagues, they knew us well. Who brought the soldiers if not them? It’s absurd how everything has changed, we were friends then suddenly one day we didn’t speak to each other any more.” The attitude advised is: “With the Serbs you have to be like this, ignore them. I don’t speak any more to the people I was friends with before the war. I wouldn’t kill them, you just have to pretend they aren’t there, ignore them. And they go away.”

10 years have passed since the conflict, Kosovo has become independent but the traumas of the conflict can still be felt, strongly even in a town like this where Serbs and Albanians lived together in much closer affinity than in other areas.

Ambitious Plans

Peja/Peć, despite the good intentions of the international organisations operating in Kosovo, has lost its multi-ethnic character. As in the town, the čaršija will have difficulty recovering its multi-ethnicity. But the lack of multi-ethnicity is not the only problem contributing to the loss of its traditional character.

Urbanisation with modern, unregulated building has irreparably transformed it. Just a few facades have been rebuilt with the help of international NGOs. Some development projects have, in fact, been drawn up. Donors include the Italian Government, the German GTZ, Muslim Aid and others. “The çarshija presents an enormous potential for tourism for the town,” says Avdyl Hoxha, the councillor responsible for tourism in Peja/Peć. “Our purpose is to make the čaršija a place of interest for tourists which will save our traditions and ancient crafts,” he added.

In order to give the çarshija back its own identity, permits for setting up commercial activities will also be streamlined. As in many other čaršijas, everything should be checked by a commission of town planning experts. This procedure is rarely respected. A number of unauthorised buildings rises discordantly amid the one and two storey shops. Demolishing them, if it ever happens, will be a difficult process.

A project for the development of this part of the town, stipulated in 2004 by the authorities of Pristina and Tirana with the collaboration of Emin Riza, a planner, expert in çarshijas, foresees the čaršija of Peja/Peć being restored faithfully to its past, even with the building of alcohol-free cafes, as tradition would expect. The consequences of the conflict are, however, so evident that it is difficult to believe this can really happen.

*To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

To Top

To Top