"Znak Pitania", Belgrade - D.Sighele

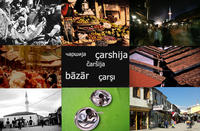

Belgrade is a city which has changed radically over the last two centuries. But, behind the town's façade, which mixes Mittel European and Socialist styles, it has not completely lost its Ottoman elements. There are no more bazaars but their spirit lives on.

Just a few metres of stone pavement, the odd cat, busy women in a hurry and some children who wonder what on earth there is to photograph in a side street like this. That's all that's left of the Belgrade carshija. Now it's one of the streets that branch out from Knez Mihailova, the commercial and trendy heart of the city.

The importance and centrality of this part of Belgrade have, however, survived and some buildings of great distinction are situated here: the Saborna Crkva, one of the most important churches in the capital, next to the residence of Princess Ljubica (wife of Prince Milos Obrenovic), which is surrounded by a townscape of neoclassical buildings and dilapidated houses, as far as the National Library which was bombed several times in both world wars.

Apart from the stone pavement there is also a restaurant, said to be the oldest building in Belgrade, a typical example of Ottoman architecture with white walls, dark woodwork and a gradually spreading out upper floor. It's called Znak Pitanja, with a question mark, because it has had so many names that have confused both inhabitants and travellers and earned it the irony of a question mark. At least this is what tourist guides and its staff say. This gives it an atmosphere midway between its Ottoman inheritance and the one from the Socialist economy.

Once there were many carshijas

The carshijas were swept away by changing times, by changing points of reference and by changing cultural and political currents.

“Several existed”, states Pedrag Markovic, one of the most authoritative observers of the urban development of Belgrade. “They perished as elsewhere, partly due to the policy of the time, partly due to the historical transformations which have touched this part of the world.

“After Serbia became independent of the Ottoman Empire, over the following 50 years Belgrade was radically transformed, like few other European cities. From a typically Ottoman town, it underwent a process of intense modernisation in the prevailing Mittel European fashion,” underlines the Serbian-Swiss scholar, Natasa Miskovic, who devoted her PhD and publication entitled “Bazari i Bulevari” to these transformations.

Western adventurers who visited Belgrade under the Ottoman dominion invariably recorded their amazement at seeing a population so mixed, in both religions and languages, that it was difficult to distinguish between the communities.

“The town was characteristically Ottoman and most of the population were Muslim. During the reign of Kraj Milos, more and more Christians of various nationalities arrived and in record time it had a Christian majority,” relates Pedrag Markovic.

New, Modern and European

With autonomy, following Serbia's independence from the Ottoman Empire, the process of forming a nation-state began. In this the modernization of the capital played a key role. Modernization was synonymous with Western instead of Ottoman, national instead of Balkan, French instead of Turkish, a trilby hat instead of a fez, ashphalt instead of cobblestones and, finally, a boulevard in the place of a Bazaar.

Dubravka Stojanovic, historian of note at the University of Belgrade, has made an in depth study of the subject in a book on the modernization of the city at the end of the 19th Century with the graphic title: “Cobblestones and Ashphalt” (“Kaldrma i asfalta”).

“The elite tried to de-Ottomanize and nationalize the culture and the city at all costs. Their attempts to transform, however, did not necessarily fit in with the mentality and customs of the citizens. It is worth mentioning for example, that at the end of the 19th Century many historical dramas were staged in Belgrade theatres, aiming at a national reawakening. They were total fiascoes though because people didn't go to see them. They preferred comedies and light opera,” comments Stojanovic.

On the other hand, modernization in Belgrade brought to this Balkan city infrastructures which few Western capitals had at the time. “In 1892 Belgrade had a system of street lighting and urban transport consisting mainly of horse-drawn trams which only existed in London, New York, Paris and Berlin,” explains the scholar Natasa Miskovic.

Modernization, but also the new national dimension, led to the death of the carshijas. “It is incredible,” says the Serbian writer, Branislav Nusic, in one of his works from the late 19th Century, “how the carshija died in so few years.”

Turkish Memories

And the Turks – an ambiguous Serbian definition which sometimes refers to the ethnically Turkish population, sometimes to Muslims without distinction of language or ethnicity – as all over the Balkans, with the withdrawal of the Ottoman Empire, left Belgrade, emptying the Begrade carshijas. “The Turks in the Balkans emigrated to Turkey, only some remaining in a few countries and towns; in Sarajevo, for example, in Skopje and in some Albanian towns. Where the Turks stayed on, the carshijas have been preserved,” explains Pedrag Markovic.

The Orthodox, who had been second class citizens for centuries, suddenly became the model for citizens propagated by the new state and its growing sense of nationhood. “There was a great change in the composition of the population, as everywhere, and the same thing happened in Istanbul,” comments Markovic.

The Turkish inheritance became inconvenient, a synonym for the past, but also a scapegoat to blame for the backwardness compared with Western Europe.

Despite this, Belgrade, under the guise of a Mittel European city, has always remained a city suspended between its Ottoman heritage, modernization and the Socialist imprint.

The Ottman heritage can still be perceived in a considerable number of the city's place-names and in the material and linguistic culture. Probably one of the more visible elements, even to the less expert, is the constantly full city cafés where people do business, socialize, live and take their place in the public space. Not only in the public sphere as described by Jurgen Habermas in the Mittel European culture, but in a much more intimate sense which derives from the kafane in the carshijas which were in some way a court and a common room for all citizens. On this historians agree: if not the carshijas themselves, at least their culture still survives in the Mittel European Belgrade.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

To Top

To Top