Cold War: Peter Mibus, border jumper for love

After 46 years, Peter Mibus returned to Romania to retrace, along with his two daughters, the escape route he undertook with his beloved Uschi to realize their dream of love

Were the Oscar nominated Canadian director Arthur Hiller still alive, we might have now a sequel of his "Love Story" movie, with the material presented by the real life story of Peter Mibus, a West German who illegally crossed the Romanian border during communism, prompted by nothing else but love – in spite of the fact that Mibus could have used his passport and cross the border legally.

The point is one: can truly understand what Mibus put himself through only if one really loved for real, at least once in one’s life.

Mibus is a Berliner, who 46 years ago lived in West Berlin, hence he was on the „good” side of the border. Still, he risked his life to get the love of his life, the woman who later became his wife and he fondly called Uschi, out of East Berlin, where she lived.

Forty-six years later, Mibus decided to track back his steps, along his two daughters, and this brought him to Romania where the investigating team met him.

A life-changing labor of love

"If you never truly loved in your life, you may not understand the choices I made", Mibus told us, while staring in front of him and walking on the Romanian bank of the Danube River, at Moldova Nouă. After four decades and a half, the now 69-year old German came back to Romania prompted by his daughters, Sophie and Anna, who wanted him to show them where exactly did he cross the Danube swimming, on the night of 22 to 23 July 1970.

That was a life-changing event they wanted to share with their father.

Mibus gave us his first-hand account when we met in Timisoara. He definitely is the only West German who embarked on such a daring and apparently unnecessary adventure, to jump the border during the communist period.

“I know, I know. You would tell me it was pointless, since I had my passport on me, and I was a West German citizen. This is why you have to learn the whole story”, Mibus tells us with a reassuring smile on his face.

Mibus was born in East Berlin, in 1947. His father was the architect for the first plant turning domestic waste into electrical power. In 1960, his father fled to West Berlin, and Peter and his mother joined him two weeks later. The Berlin wall was not yet erected at the time.

Only a student, when he fell in love

They all became West German citizens, and accessed an easier life style. At 22, Mibus was a student, owned a car, and had a permit to visit East Berlin. This is how he met Ursula.

“My Uschi was hitch-hiking. This is how we met. I stopped the car and invited her in. She said she was not going to climb in a West-German’s car. Then I asked her if she wanted to meet me at another place and time. She agreed. This is how we started, at first writing each other. She was 24 and already a teacher,” Mibus recalls fondly.

After less than three months since their first meeting, Mibus was certain she was the one for him, and that they had to live together in West Germany.

“Our meetings had to end before midnight, because the law said I was due to go back to West Berlin by midnight. We could not go on like this. I decided to bring her to West Berlin. But the border was too well guarded and dangerous for us to risk jumping it. So, we thought we would do that from Romania, swimming over the Danube River, since we both were good swimmers”, Mibus told us when we met in Romania.

He never laid foot in Romania before

He had never been to Romania and was unaware of the brutality the Securitate and the border police were deploying when dealing with border jumpers. In all, there were about 800 East Germans who chose to come to Romania in order to jump its border with Yugoslavia, and thus make their way to West Germany. There were also tens of thousands of Romanians who thought of the same border as an escape route. They were called „frontieriştii", or the border jumpers, and their plight is documented in the investigative reports filed by this journalistic team.

It took only a few weeks time for Peter and Uschi to get the transit visas for Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, since they gave Bulgaria as their final vacationing destination.

How deciding for the Romania-Yugoslavia route came about

“An easier way out would have been to get a false West German passport for Uschi, but I did not have that kind of money. I was only a student at the time. So, I put Uschi on the train for Prague, while I drove in the same direction. We met there and spent one night together. The next day we arrived in Budapest, and visited some friends. When we left for Romania, we decided to see how things were at the Hungarian-Yugoslav border. The border check point came right after a hair-pin curve, so we suddenly found ourselves confronted by the Hungarian border guards, and a representative of their secret police. There was no turning back for us, but to stick to the story we made up beforehand: that Uschi was hitch hiking, that I took her in my car in Budapest, and that we were both heading to Romania, but we missed the right track.”

Pennies from panties, for the road

After they were interrogated for a couple of hours, the two of them were turned back, and so they made their way to the border check point in Nădlac, to enter Romania. Uschi had visited the country before. Their first stop was in Union Square, in Timișoara.

“Here was the street leading to Oraviţa. This is where we stopped. The square looks different now. We had a few pairs of pantyhose on us, which we sold. We also sold a portable radio set. Thus we ended up with 400 Ost Deutsch Marks, 10 East German Marks, and the lei we got with selling our stuff”, Mibus said, while showing his daughters around.

The road takes one to Oraviţa, indeed, but Mibus took to the mountain area, towards Cărbunari, on a loggers road, away from the beaten track which took one to Naidăș, and then straight along the Danube River banks.

”We had a map of Eastern Europe printed in 1968. Look … it shows the road to Cărbunari as the only option. So we reached Moldova Nouă, and put ourselves in a B&B. That building is not standing anymore. Then we went to a restaurant which was serving meals in its garden. That venue is gone too. So, we talked to the German-speaking Schwaben living in the area, and we told them we were from West Germany, and that we planned to cross the border to Yugoslavia by car,” – this was their cover story to justify their presence in the border area. They also made friends with two Schwaben and together took a walk the next day on the River banks.

2016 – An emotional return to the Danube river

Back in 2016, the arrival at Moldova Nouă and the sight of the Danube River proved very emotional to Mibus.

The River banks really come closer in this area.

“While the four of us walked on the River bank – 46 years ago – a border guard jumped out of a bush and started to move his weapon around. I showed him my West-German passport, and told him the other three people were Romanians. He believed me and did not check their documentation. I was gentle and kept my cool all the time. This experience, early on, in Romania, helped me a lot later in life, because, after that, nothing seemed too hard or impossible to accomplish,” Mibus recalls.

He is now proudly standing for a photo-op with two of the nowadays border guards who came our way.

"Look, we’re friends now! But what could have happened 46 years ago?!" Mibus ponders while having his photo taken.

Back again to 1970, Mibus was afraid only that the island right in the middle of the River at Moldova Nouă will trick them.

“My concern was that the water currents would push us towards the Romanian territory again”.

Peter and Uschi chose to flee over the border that night. They drove for a couple of kilometers away from Moldova Nouă and towards Naidăș. They left their Volkswagen car on a road in an open field, and crossed a wheat field to get to the Danube River.

"This is the high-voltage power line pole where we rested for a few minutes. It was on the night of 22 to 23 July. We made it to the wooded area, right on the River bank. It was 01:00 at night. We were in a marsh area. The border guards were patrolling on boats. Their search-light pierced some 50 meters into the woods bordering the River. We waited for one hour. They did not pass again. We knew then that we had one hour to make the crossing. We had no Neopren rubber suits, and did not put any oil on our skins either. We started back-swimming, and then, only a few meters into the water, we noticed the huge observation tower, which laid behind us. And it was a full moon. So, the visibility was good for all parties. Since that year a lot of flooding took place, the Danube was filled with floating debris and pieces of wood. We kept each other afloat with a make-shift rope made of our clothes, tied together. The map, the binoculars, and all our belongings were in the car we had abandoned. Half way through our crossing, we started feeling the effect of the cold water. We were exhausted. Uschi was the one who pulled me out of the water. We were on the Serbian bank. We made it!“.

Peter Mibus was not aware of the dangers, or that him swimming along Uschi doubled the danger, instead of mitigating it.

“I know, I know. Everybody keeps telling me that, but what kind of a man would I have been to tell my girlfriend: you go swim, and I will wait for you on the other side? I could not have done that. Before we entered the water, Uschi told me to go back. But I told her: you see only the smog, but to me everything is clear.”

Westwards they went

So, they boarded the bus to Pozarevac, and then another bus to Belgrade.

"We were both wet. I was wearing shorts and was barefoot; she had some dry clothes on her. But the Yugoslavians were friendly. It was 05:00 in the morning and no one told on us. We knew we had to get to the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Belgrade, and that we had the right, and they had the obligation to issue West-German passports to us.

At the embassy we were taken to a room where we could nap for a while. Then they gave us money to buy train tickets to Germany and issued a West-German passport for Uschi. We had no entry visas for Yugoslavia and that might have been a problem when exiting the country, but the embassy officials told us to claim we had a very urgent and serious problem to solve back home, and this was why we had no time to go to the local Yugoslav Militia to ask for an entry visa."

A dream come true and then blown away by illness

They made it alright to West Germany, and in September they got married. In a few months she was pregnant. But the dream life which they turned to reality was to soon turn into a nightmare: Uschi was diagnosed with lung cancer and given six months to live. Because of the radiation treatment she lost the pregnancy.

“They said she would live six more months; she lived 11 months,” Mibus says, bursting into tears, while his daughters from a second marriage comfort him.

Peter Mibus remarried ten years later, and had Sophie and Anna, who are now accompanying him on this trip.

Revenge, revenge, revenge

Mibus was angered that the communist regime in East Germany and STASI did not allow Uschi to ever see her parents again, before dieing; neither did it allow her parents to attend her funeral.

This turned Mibus into a man on a revenge mission.

He advised some of his friends in East Germany on how to flee the country using the same route he did, via Moldova Nouă, in Romania. In 1971, his friend Siegfried made an attempt, but was arrested, and since he was an active member of the military in East Germany, he was given a 7-year prison term, but was pardoned after one year in prison.

Between 1972 and 1974 he personally helped two East Germans to get to West Germany by driving them over the border, in his modified car trunk, which accommodated one person.

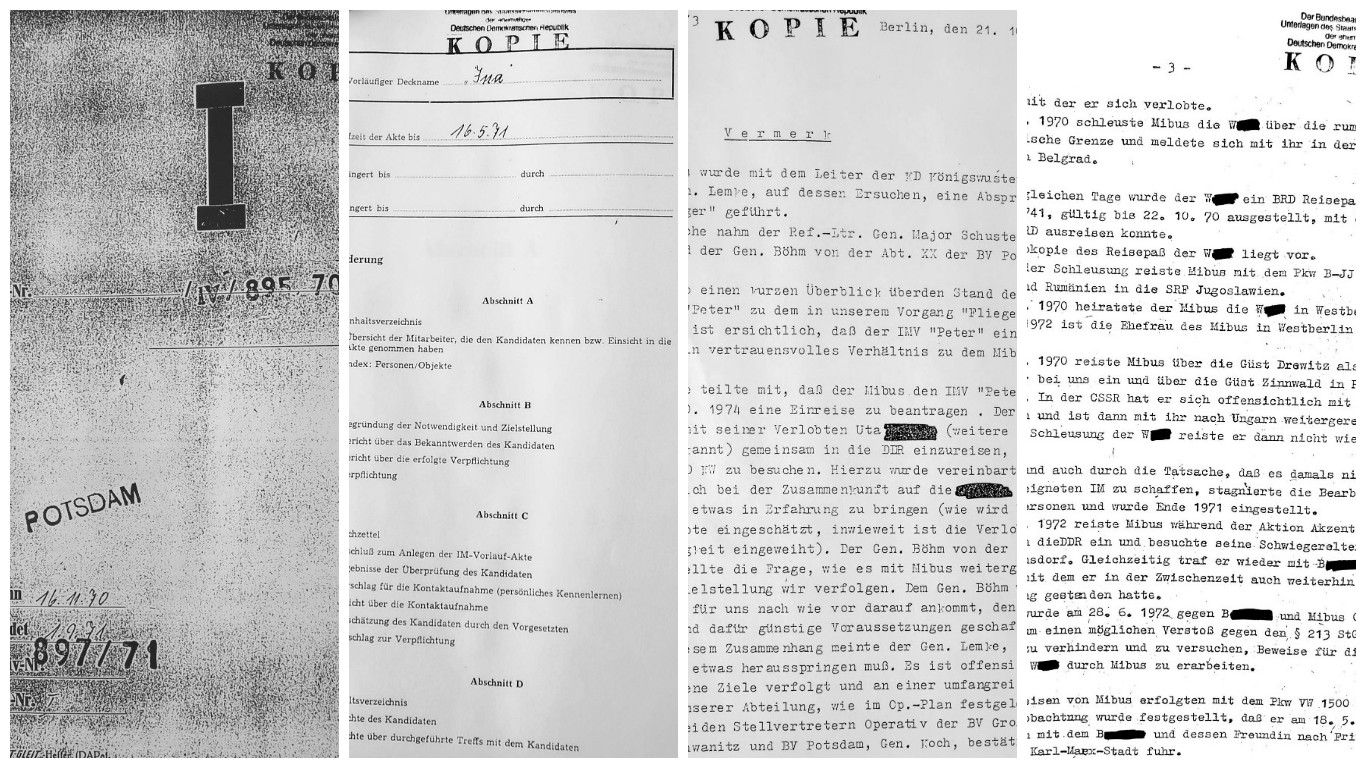

After 1989 Mibus got access to his file with the STASI.

“What I read in that STASI file appalled me. STASI was moving on Uschi, to ask her become an agent in West Berlin, prior to her flight. After that, it started spying on us using our friends at the time. For years after that, STASI was still trying to figure out how she made it on the other side of the border. The documents show there was not much cooperation between STASI and the Romanian Securitate. The Romanians did not sent any information on the car with West-German plates and documentation they found near Moldova Nouă. Only after 1974, they told STASI that we used Romania as a springboard for fleeing East Germany. STASI knew I was illegally helping people to flee the Democrat Republic, but were certain I was running a criminal ring, and so they waited for the right time to make their move on me. They were wrong: I was a sole operator; and I was right to stop just in time, it seems.”

Mibus’ daughters give him a long stare. This 2016 summer experience, when the girls tried to understand their father’s choices, seem like a true eye-opener to them on what real challenges in life are.

Had he ever had any regrets for fleeing via Romania, and why did he come back only so late after the fact, to revisit the places that dramatically changed his life, are questions on Mibus’ mind.

“It was a sad story, that in spite of our lucky escape we were separated so early in life by death. I have never come back to Romania before, because painful memories are difficult to relive and put into words. Everything I told you happened for real. One more word, any sentimental undertone would be an offense to the memory of my late wife. Any daredevil act I might have done may be justified in only one possible way: I was truly in love”.

We left Peter Mibus carrying the natural feeling that we would meet again, as natural was our meeting from the on-start.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Cold War: Peter Mibus, border jumper for love

After 46 years, Peter Mibus returned to Romania to retrace, along with his two daughters, the escape route he undertook with his beloved Uschi to realize their dream of love

Were the Oscar nominated Canadian director Arthur Hiller still alive, we might have now a sequel of his "Love Story" movie, with the material presented by the real life story of Peter Mibus, a West German who illegally crossed the Romanian border during communism, prompted by nothing else but love – in spite of the fact that Mibus could have used his passport and cross the border legally.

The point is one: can truly understand what Mibus put himself through only if one really loved for real, at least once in one’s life.

Mibus is a Berliner, who 46 years ago lived in West Berlin, hence he was on the „good” side of the border. Still, he risked his life to get the love of his life, the woman who later became his wife and he fondly called Uschi, out of East Berlin, where she lived.

Forty-six years later, Mibus decided to track back his steps, along his two daughters, and this brought him to Romania where the investigating team met him.

A life-changing labor of love

"If you never truly loved in your life, you may not understand the choices I made", Mibus told us, while staring in front of him and walking on the Romanian bank of the Danube River, at Moldova Nouă. After four decades and a half, the now 69-year old German came back to Romania prompted by his daughters, Sophie and Anna, who wanted him to show them where exactly did he cross the Danube swimming, on the night of 22 to 23 July 1970.

That was a life-changing event they wanted to share with their father.

Mibus gave us his first-hand account when we met in Timisoara. He definitely is the only West German who embarked on such a daring and apparently unnecessary adventure, to jump the border during the communist period.

“I know, I know. You would tell me it was pointless, since I had my passport on me, and I was a West German citizen. This is why you have to learn the whole story”, Mibus tells us with a reassuring smile on his face.

Mibus was born in East Berlin, in 1947. His father was the architect for the first plant turning domestic waste into electrical power. In 1960, his father fled to West Berlin, and Peter and his mother joined him two weeks later. The Berlin wall was not yet erected at the time.

Only a student, when he fell in love

They all became West German citizens, and accessed an easier life style. At 22, Mibus was a student, owned a car, and had a permit to visit East Berlin. This is how he met Ursula.

“My Uschi was hitch-hiking. This is how we met. I stopped the car and invited her in. She said she was not going to climb in a West-German’s car. Then I asked her if she wanted to meet me at another place and time. She agreed. This is how we started, at first writing each other. She was 24 and already a teacher,” Mibus recalls fondly.

After less than three months since their first meeting, Mibus was certain she was the one for him, and that they had to live together in West Germany.

“Our meetings had to end before midnight, because the law said I was due to go back to West Berlin by midnight. We could not go on like this. I decided to bring her to West Berlin. But the border was too well guarded and dangerous for us to risk jumping it. So, we thought we would do that from Romania, swimming over the Danube River, since we both were good swimmers”, Mibus told us when we met in Romania.

He never laid foot in Romania before

He had never been to Romania and was unaware of the brutality the Securitate and the border police were deploying when dealing with border jumpers. In all, there were about 800 East Germans who chose to come to Romania in order to jump its border with Yugoslavia, and thus make their way to West Germany. There were also tens of thousands of Romanians who thought of the same border as an escape route. They were called „frontieriştii", or the border jumpers, and their plight is documented in the investigative reports filed by this journalistic team.

It took only a few weeks time for Peter and Uschi to get the transit visas for Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, since they gave Bulgaria as their final vacationing destination.

How deciding for the Romania-Yugoslavia route came about

“An easier way out would have been to get a false West German passport for Uschi, but I did not have that kind of money. I was only a student at the time. So, I put Uschi on the train for Prague, while I drove in the same direction. We met there and spent one night together. The next day we arrived in Budapest, and visited some friends. When we left for Romania, we decided to see how things were at the Hungarian-Yugoslav border. The border check point came right after a hair-pin curve, so we suddenly found ourselves confronted by the Hungarian border guards, and a representative of their secret police. There was no turning back for us, but to stick to the story we made up beforehand: that Uschi was hitch hiking, that I took her in my car in Budapest, and that we were both heading to Romania, but we missed the right track.”

Pennies from panties, for the road

After they were interrogated for a couple of hours, the two of them were turned back, and so they made their way to the border check point in Nădlac, to enter Romania. Uschi had visited the country before. Their first stop was in Union Square, in Timișoara.

“Here was the street leading to Oraviţa. This is where we stopped. The square looks different now. We had a few pairs of pantyhose on us, which we sold. We also sold a portable radio set. Thus we ended up with 400 Ost Deutsch Marks, 10 East German Marks, and the lei we got with selling our stuff”, Mibus said, while showing his daughters around.

The road takes one to Oraviţa, indeed, but Mibus took to the mountain area, towards Cărbunari, on a loggers road, away from the beaten track which took one to Naidăș, and then straight along the Danube River banks.

”We had a map of Eastern Europe printed in 1968. Look … it shows the road to Cărbunari as the only option. So we reached Moldova Nouă, and put ourselves in a B&B. That building is not standing anymore. Then we went to a restaurant which was serving meals in its garden. That venue is gone too. So, we talked to the German-speaking Schwaben living in the area, and we told them we were from West Germany, and that we planned to cross the border to Yugoslavia by car,” – this was their cover story to justify their presence in the border area. They also made friends with two Schwaben and together took a walk the next day on the River banks.

2016 – An emotional return to the Danube river

Back in 2016, the arrival at Moldova Nouă and the sight of the Danube River proved very emotional to Mibus.

The River banks really come closer in this area.

“While the four of us walked on the River bank – 46 years ago – a border guard jumped out of a bush and started to move his weapon around. I showed him my West-German passport, and told him the other three people were Romanians. He believed me and did not check their documentation. I was gentle and kept my cool all the time. This experience, early on, in Romania, helped me a lot later in life, because, after that, nothing seemed too hard or impossible to accomplish,” Mibus recalls.

He is now proudly standing for a photo-op with two of the nowadays border guards who came our way.

"Look, we’re friends now! But what could have happened 46 years ago?!" Mibus ponders while having his photo taken.

Back again to 1970, Mibus was afraid only that the island right in the middle of the River at Moldova Nouă will trick them.

“My concern was that the water currents would push us towards the Romanian territory again”.

Peter and Uschi chose to flee over the border that night. They drove for a couple of kilometers away from Moldova Nouă and towards Naidăș. They left their Volkswagen car on a road in an open field, and crossed a wheat field to get to the Danube River.

"This is the high-voltage power line pole where we rested for a few minutes. It was on the night of 22 to 23 July. We made it to the wooded area, right on the River bank. It was 01:00 at night. We were in a marsh area. The border guards were patrolling on boats. Their search-light pierced some 50 meters into the woods bordering the River. We waited for one hour. They did not pass again. We knew then that we had one hour to make the crossing. We had no Neopren rubber suits, and did not put any oil on our skins either. We started back-swimming, and then, only a few meters into the water, we noticed the huge observation tower, which laid behind us. And it was a full moon. So, the visibility was good for all parties. Since that year a lot of flooding took place, the Danube was filled with floating debris and pieces of wood. We kept each other afloat with a make-shift rope made of our clothes, tied together. The map, the binoculars, and all our belongings were in the car we had abandoned. Half way through our crossing, we started feeling the effect of the cold water. We were exhausted. Uschi was the one who pulled me out of the water. We were on the Serbian bank. We made it!“.

Peter Mibus was not aware of the dangers, or that him swimming along Uschi doubled the danger, instead of mitigating it.

“I know, I know. Everybody keeps telling me that, but what kind of a man would I have been to tell my girlfriend: you go swim, and I will wait for you on the other side? I could not have done that. Before we entered the water, Uschi told me to go back. But I told her: you see only the smog, but to me everything is clear.”

Westwards they went

So, they boarded the bus to Pozarevac, and then another bus to Belgrade.

"We were both wet. I was wearing shorts and was barefoot; she had some dry clothes on her. But the Yugoslavians were friendly. It was 05:00 in the morning and no one told on us. We knew we had to get to the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Belgrade, and that we had the right, and they had the obligation to issue West-German passports to us.

At the embassy we were taken to a room where we could nap for a while. Then they gave us money to buy train tickets to Germany and issued a West-German passport for Uschi. We had no entry visas for Yugoslavia and that might have been a problem when exiting the country, but the embassy officials told us to claim we had a very urgent and serious problem to solve back home, and this was why we had no time to go to the local Yugoslav Militia to ask for an entry visa."

A dream come true and then blown away by illness

They made it alright to West Germany, and in September they got married. In a few months she was pregnant. But the dream life which they turned to reality was to soon turn into a nightmare: Uschi was diagnosed with lung cancer and given six months to live. Because of the radiation treatment she lost the pregnancy.

“They said she would live six more months; she lived 11 months,” Mibus says, bursting into tears, while his daughters from a second marriage comfort him.

Peter Mibus remarried ten years later, and had Sophie and Anna, who are now accompanying him on this trip.

Revenge, revenge, revenge

Mibus was angered that the communist regime in East Germany and STASI did not allow Uschi to ever see her parents again, before dieing; neither did it allow her parents to attend her funeral.

This turned Mibus into a man on a revenge mission.

He advised some of his friends in East Germany on how to flee the country using the same route he did, via Moldova Nouă, in Romania. In 1971, his friend Siegfried made an attempt, but was arrested, and since he was an active member of the military in East Germany, he was given a 7-year prison term, but was pardoned after one year in prison.

Between 1972 and 1974 he personally helped two East Germans to get to West Germany by driving them over the border, in his modified car trunk, which accommodated one person.

After 1989 Mibus got access to his file with the STASI.

“What I read in that STASI file appalled me. STASI was moving on Uschi, to ask her become an agent in West Berlin, prior to her flight. After that, it started spying on us using our friends at the time. For years after that, STASI was still trying to figure out how she made it on the other side of the border. The documents show there was not much cooperation between STASI and the Romanian Securitate. The Romanians did not sent any information on the car with West-German plates and documentation they found near Moldova Nouă. Only after 1974, they told STASI that we used Romania as a springboard for fleeing East Germany. STASI knew I was illegally helping people to flee the Democrat Republic, but were certain I was running a criminal ring, and so they waited for the right time to make their move on me. They were wrong: I was a sole operator; and I was right to stop just in time, it seems.”

Mibus’ daughters give him a long stare. This 2016 summer experience, when the girls tried to understand their father’s choices, seem like a true eye-opener to them on what real challenges in life are.

Had he ever had any regrets for fleeing via Romania, and why did he come back only so late after the fact, to revisit the places that dramatically changed his life, are questions on Mibus’ mind.

“It was a sad story, that in spite of our lucky escape we were separated so early in life by death. I have never come back to Romania before, because painful memories are difficult to relive and put into words. Everything I told you happened for real. One more word, any sentimental undertone would be an offense to the memory of my late wife. Any daredevil act I might have done may be justified in only one possible way: I was truly in love”.

We left Peter Mibus carrying the natural feeling that we would meet again, as natural was our meeting from the on-start.