The defector who took the Romanian State to court

Considered as dangerous as criminals by the Romanian regime, defectors were long prosecuted and criminalized. One of them now seeks justice for all Romanian defectors

(Originally published in Romanian by miscareaderezistenta.ro on May 4th, 2016. This article is part of an investigative series developed within the "Reporters in the field" program, funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung in partnership with the Berliner Journalisten Schule. A selection of the articles issued within this series is now also proposed to the readers of OBC Transeuropa)

The story of Mihai Stăuceanu could easily be turned into a script for a movie. It has so many sides, that it is difficult to get it all in a single piece of writing. Stăuceanu is the text-book case for a defector. His tribulations at the Romanian border, in Yugoslavia, then in the refugee camp in Italy and finally in Canada (his final destination) could make only the first part in a several episodes series.

But the next episodes of Stăuceanu’s life read even better.

A person worth surveilling

When he asked for his Securitate file from the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Files, or CNSAS , Stăuceanu was in for a big surprise, finding out the names, the many names of people he thought were his friends, both in Romania and in Canada, where he fled, but who proved to be informants on the Securitate pay-roll.

Because he defected successfully, Stăuceanu, a simple electrician, became a person worth investing State funds to follow.

Stăuceanu found these were reasons enough to take the Romanian State to court in order to create a precedent: a ruling that could benefit all former defectors, at the end of the day. He has decided to bring his case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), if Romanian courts will not grant him satisfaction.

Stăuceanu’s first attempt

To some, the realization that the communist regime was toxic, came early in life. And the desire to live in a free world followed.

Stăuceanu first jumped border when he was 18, accompanied by a friend and co-worker from the Reşiţa city. They made their attempt at crossing the border during a foggy and rainy day, on May 4, 1975, in the area of the Vărădia village, Caraş-Severin County.

Out of fright and high emotions, they accidentally touched a wire that triggered a warning system which further frightened them; they ran like crazy, only to stop in a barbed-wire fence. Only in the morning they would discover that their clothes were torn, and their bodies bloodied from that encounter with the fence. They stripped and washed their clothes in the nearby Nera River.

They wandered for three days, till they reached the railway station in Belgrade. Unfortunately, they were discovered by the Yugoslav police on the train to Vienna. They were tried for illegal border-crossing, sent a few days in prison at the Padinska Skela, and then sent back to the Romanian authorities.

The two of them were handed over to the Romanian border-guards on May 7, 1975, at the Stamora-Moraviţa border control point. The Romanian border-guards tied their hands at their backs using some wire, blindfolded them, and took them to their headquarters in Oraviţa. On the road, they repeatedly hit them over their heads and in their torso areas. This was the border-guards way to remind them their current status as “traitors”.

“I have no idea how long it actually took to get from Stamora Moraviţa to Oraviţa, but it seemed ages, and I started to regret the border-guards did not put a bullet in my head while attempting to cross to the other side”, Stăuceanu recalls now.

“It may be that we left behind ample proof of our attempt at crossing the border – meaning parts of clothing, foot prints, and the alarm switch we triggered – that they were particularly mad at us. It may be that the prospect of not having caught us scared them, as it carried a lot of consequences for them” Stăuceanu adds.

“We spent 24-hours in the arrest room in Oraviţa, while still having our hands tied at the back, our eyes blindfolded, and with no permission to use the toilet, sit or at least stay on our knees,” he recalls.

Public trial for public humiliation

Major Crăciun Gheorghe was responsible for the official inquiry on the attempted escape. He asked the prosecutor to have their trial conducted in Vărădia – the village closest to the area they attempted to cross the border – in order to set an example for the local population.

The public trial took place on May 23, 1975 in the Cultural House of the village of Vărădia, where the locals were rounded up and made to witness it. The boys were sentenced to a 22-month prison-term, and they were immediately taken to the penitentiary in the city of Caransebeş.

Stăuceanu’s brother, Nicolae Stăuceanu, who had already served time for his own attempt to illegally cross the border back in 1972, appealed the ruling at the Reşiţa Tribunal. The appeal court decided to lower the sentence to 12 months in prison, taking into account that Mihai Stăuceanu was at the time barely over 18. He was then taken to the prison in Gherla, to serve his time.

As dangerous as criminals

“The Gherla prison was for border jumpers and people sentenced to over 20-year terms. I believe at the time there were some 200 to 250 border jumpers, like myself. The first-time offenders were kept completely separate from the rest, and were working at the water management plant in Dej city”, recalls Stăuceanu.

“The detention regime at Gherla was probably very similar to the extermination regime applied in the Nazi camps: 10 to 12 hours of physical work on a construction site, which was cordoned off with double fences of barbed-wire and with guarding towers, exactly like those to be found at the border. I could see for myself now that the country I was living in was nothing else but a big prison, as similar systems kept in both inmates inside the prisons, and regular citizens inside the country. Also, the fact that border-jumpers were put in the same prison with hardened criminals, though their only crime was their attempt to defect, showed how the communist regime regarded us: we were as dangerous to the regime as the actual criminals were to the society at large” Stăuceanu thinks.

One devious trick the communist regime performed in its legal system, in 1969, was to wipe out any reference to political offenses against the State, and turn those “crimes” into regular crimes, penalized by the country’s criminal laws. Thus, the regime got a face-lift, as becoming more democratic, when, in fact, it continued to punish defectors.

Once he got out of the Gherla prison, Stăuceanu became a target for the Securitate. After he was released, his parents in Liteni told him the Securitate people already inquired about him. According to a note sent by the penitentiary to the Securitate office in the Suceava County, were his family resided, Stăuceanu and his family were to be closely followed by the Securitate informants. Stăuceanu found this note in his Securitate file, which he examined at the CNSAS.

The Steel Works at Reşiţa refused to hire him, though he had worked there before; he was told they had no place for “traitors”. After many attempts to find employment, he got one with a small division servicing elevators for the municipal real-estate of the Reşiţa city.

A new attempt at illegal crossing of the border

One year after getting out of prison, Stăuceanu started again to consider jumping the border.

“I was getting close to the border, when I was caught by the border-guards. They kept pressing me to confess that my intention was to cross it illegally. They did not find any documents on me or my friend, who wanted to help me – so they had nothing to prove my intent, except from forcing me into a confession. The beating I got this time, in the border-guards tower at Naidăş was far worse than the first one. But knowing what lied ahead of me, I said to myself I would rather die than admit I wanted to cross the border.”

Five years after his first attempt at crossing the border, Stăuceanu decided to have a second go, this time, together with a close-friend but also with another person he did not know.

In the fall of 1981, his second attempt was successful. They used the Naidăş-Biserica Albă border area. The Yugoslav border-guards got to them before they were able to reach Biserica Albă; it may be that they unwittingly touched a warning system. They were sentenced to a 30-day prison-time, for illegal border-crossing. Stăuceanu reached now the prison in Vrsec, along other 40 something Romanian defectors.

They were transferred to another penitentiary, at Padinska Skela, near Belgrade. The system there was different: defectors from the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, and all over the Eastern-block waited each Friday evening to find their names on a list of 45 people. The Yugoslav authorities took those out of the prison and transported them to other borders, presumably to Austria or Italy.

Stăuceanu spent 15 days at Padinska Skela. The living conditions there were appalling: they slept on mattresses placed on the floor, it was filthy, and they went on a hunger-strike to got access to showers.

“We were treated worse than animals. Serbs caught us, and now had no idea what to do with us” Stăuceanu says now. His turn came to be set free at a Western border. On the road to Maribor, the bus stopped and two to three people were set free. He was among the last five in the bus, who were set free close to the Italian border, in the Nova Gorica-Monfalcone area.

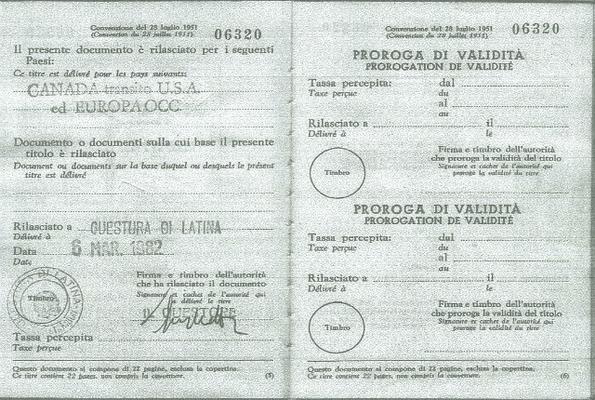

They were registered by the police in Monfalcone, had train tickets provided, and were sent to the refugee camp in the Italian city of Latina, close to Rome.

“Following the inquiry conducted by a four or five people committee, I got my political refugee status based on the documents that proved my time in the prison at Gherla”, he says.

He was accepted by Canada, to emigrate with the status of “voluntary exile.” A new life was awaiting him on the new continent.

An adventure for the whole family

Between 1984 and 1989, Stăuceanu came back to Romania four times – the trips were mentioned in his Securitate file, now held by the CNSAS. He was under close surveillance both in Montreal, Canada, where he settled, and in Romania. His trips aimed at legally getting out of the country his brother and his brother’s family, who were living in Lugoj, Timiş County.

After five years of failed attempts, Stăuceanu went on a hunger-strike in front of the Romanian Embassy in Ottawa. He started it on September 25, 1989, and stopped ten days later, when he got the approval for his brother to leave Romania, accompanied by his own family. On December 5, 1989, they all arrived to Canada.

Stăuceanu’s fights for a legal precedent

Stăuceanu took the Romanian State to court. He filed two actions with the Suceava Tribunal. One with the Civil Court, under Law 221/2009, which deals with the political convictions inflicted between 1945 and 1989; the file number is 3675/86/2014; the second action he filed was with the Administrative Court, against the public institution responsible to make financial reparations to the victims of political trials during communism; the file number is 4811/86/2014.

The ruling on the latter was suspended until the Supreme Court of Justice will rule on the appeal to his first civil action, which is now under consideration by this court, as file number 254/39/2015.

Stăuceanu hopes the ruling in his case would serve as a legal precedent for other former border-jumpers to use. The court of first instance agreed that his conviction as a criminal according to the ruling 158, made public on May 23, 1975 by the Oraviţa Court, was in fact politically motivated. But the financial compensation is still pending a ruling from the Supreme Court.

“I felt I had to leave that communist State at all costs; it imposed on its citizens a life-style I could not agree with: mendacity in all aspects of life, and the personality cult for dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. I understood, early on in life, that we were all inhabiting a large prison cell, called the Socialist Republic of Romania”, Stăuceanu says.

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

The defector who took the Romanian State to court

Considered as dangerous as criminals by the Romanian regime, defectors were long prosecuted and criminalized. One of them now seeks justice for all Romanian defectors

(Originally published in Romanian by miscareaderezistenta.ro on May 4th, 2016. This article is part of an investigative series developed within the "Reporters in the field" program, funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung in partnership with the Berliner Journalisten Schule. A selection of the articles issued within this series is now also proposed to the readers of OBC Transeuropa)

The story of Mihai Stăuceanu could easily be turned into a script for a movie. It has so many sides, that it is difficult to get it all in a single piece of writing. Stăuceanu is the text-book case for a defector. His tribulations at the Romanian border, in Yugoslavia, then in the refugee camp in Italy and finally in Canada (his final destination) could make only the first part in a several episodes series.

But the next episodes of Stăuceanu’s life read even better.

A person worth surveilling

When he asked for his Securitate file from the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Files, or CNSAS , Stăuceanu was in for a big surprise, finding out the names, the many names of people he thought were his friends, both in Romania and in Canada, where he fled, but who proved to be informants on the Securitate pay-roll.

Because he defected successfully, Stăuceanu, a simple electrician, became a person worth investing State funds to follow.

Stăuceanu found these were reasons enough to take the Romanian State to court in order to create a precedent: a ruling that could benefit all former defectors, at the end of the day. He has decided to bring his case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), if Romanian courts will not grant him satisfaction.

Stăuceanu’s first attempt

To some, the realization that the communist regime was toxic, came early in life. And the desire to live in a free world followed.

Stăuceanu first jumped border when he was 18, accompanied by a friend and co-worker from the Reşiţa city. They made their attempt at crossing the border during a foggy and rainy day, on May 4, 1975, in the area of the Vărădia village, Caraş-Severin County.

Out of fright and high emotions, they accidentally touched a wire that triggered a warning system which further frightened them; they ran like crazy, only to stop in a barbed-wire fence. Only in the morning they would discover that their clothes were torn, and their bodies bloodied from that encounter with the fence. They stripped and washed their clothes in the nearby Nera River.

They wandered for three days, till they reached the railway station in Belgrade. Unfortunately, they were discovered by the Yugoslav police on the train to Vienna. They were tried for illegal border-crossing, sent a few days in prison at the Padinska Skela, and then sent back to the Romanian authorities.

The two of them were handed over to the Romanian border-guards on May 7, 1975, at the Stamora-Moraviţa border control point. The Romanian border-guards tied their hands at their backs using some wire, blindfolded them, and took them to their headquarters in Oraviţa. On the road, they repeatedly hit them over their heads and in their torso areas. This was the border-guards way to remind them their current status as “traitors”.

“I have no idea how long it actually took to get from Stamora Moraviţa to Oraviţa, but it seemed ages, and I started to regret the border-guards did not put a bullet in my head while attempting to cross to the other side”, Stăuceanu recalls now.

“It may be that we left behind ample proof of our attempt at crossing the border – meaning parts of clothing, foot prints, and the alarm switch we triggered – that they were particularly mad at us. It may be that the prospect of not having caught us scared them, as it carried a lot of consequences for them” Stăuceanu adds.

“We spent 24-hours in the arrest room in Oraviţa, while still having our hands tied at the back, our eyes blindfolded, and with no permission to use the toilet, sit or at least stay on our knees,” he recalls.

Public trial for public humiliation

Major Crăciun Gheorghe was responsible for the official inquiry on the attempted escape. He asked the prosecutor to have their trial conducted in Vărădia – the village closest to the area they attempted to cross the border – in order to set an example for the local population.

The public trial took place on May 23, 1975 in the Cultural House of the village of Vărădia, where the locals were rounded up and made to witness it. The boys were sentenced to a 22-month prison-term, and they were immediately taken to the penitentiary in the city of Caransebeş.

Stăuceanu’s brother, Nicolae Stăuceanu, who had already served time for his own attempt to illegally cross the border back in 1972, appealed the ruling at the Reşiţa Tribunal. The appeal court decided to lower the sentence to 12 months in prison, taking into account that Mihai Stăuceanu was at the time barely over 18. He was then taken to the prison in Gherla, to serve his time.

As dangerous as criminals

“The Gherla prison was for border jumpers and people sentenced to over 20-year terms. I believe at the time there were some 200 to 250 border jumpers, like myself. The first-time offenders were kept completely separate from the rest, and were working at the water management plant in Dej city”, recalls Stăuceanu.

“The detention regime at Gherla was probably very similar to the extermination regime applied in the Nazi camps: 10 to 12 hours of physical work on a construction site, which was cordoned off with double fences of barbed-wire and with guarding towers, exactly like those to be found at the border. I could see for myself now that the country I was living in was nothing else but a big prison, as similar systems kept in both inmates inside the prisons, and regular citizens inside the country. Also, the fact that border-jumpers were put in the same prison with hardened criminals, though their only crime was their attempt to defect, showed how the communist regime regarded us: we were as dangerous to the regime as the actual criminals were to the society at large” Stăuceanu thinks.

One devious trick the communist regime performed in its legal system, in 1969, was to wipe out any reference to political offenses against the State, and turn those “crimes” into regular crimes, penalized by the country’s criminal laws. Thus, the regime got a face-lift, as becoming more democratic, when, in fact, it continued to punish defectors.

Once he got out of the Gherla prison, Stăuceanu became a target for the Securitate. After he was released, his parents in Liteni told him the Securitate people already inquired about him. According to a note sent by the penitentiary to the Securitate office in the Suceava County, were his family resided, Stăuceanu and his family were to be closely followed by the Securitate informants. Stăuceanu found this note in his Securitate file, which he examined at the CNSAS.

The Steel Works at Reşiţa refused to hire him, though he had worked there before; he was told they had no place for “traitors”. After many attempts to find employment, he got one with a small division servicing elevators for the municipal real-estate of the Reşiţa city.

A new attempt at illegal crossing of the border

One year after getting out of prison, Stăuceanu started again to consider jumping the border.

“I was getting close to the border, when I was caught by the border-guards. They kept pressing me to confess that my intention was to cross it illegally. They did not find any documents on me or my friend, who wanted to help me – so they had nothing to prove my intent, except from forcing me into a confession. The beating I got this time, in the border-guards tower at Naidăş was far worse than the first one. But knowing what lied ahead of me, I said to myself I would rather die than admit I wanted to cross the border.”

Five years after his first attempt at crossing the border, Stăuceanu decided to have a second go, this time, together with a close-friend but also with another person he did not know.

In the fall of 1981, his second attempt was successful. They used the Naidăş-Biserica Albă border area. The Yugoslav border-guards got to them before they were able to reach Biserica Albă; it may be that they unwittingly touched a warning system. They were sentenced to a 30-day prison-time, for illegal border-crossing. Stăuceanu reached now the prison in Vrsec, along other 40 something Romanian defectors.

They were transferred to another penitentiary, at Padinska Skela, near Belgrade. The system there was different: defectors from the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, Romania, Russia, and all over the Eastern-block waited each Friday evening to find their names on a list of 45 people. The Yugoslav authorities took those out of the prison and transported them to other borders, presumably to Austria or Italy.

Stăuceanu spent 15 days at Padinska Skela. The living conditions there were appalling: they slept on mattresses placed on the floor, it was filthy, and they went on a hunger-strike to got access to showers.

“We were treated worse than animals. Serbs caught us, and now had no idea what to do with us” Stăuceanu says now. His turn came to be set free at a Western border. On the road to Maribor, the bus stopped and two to three people were set free. He was among the last five in the bus, who were set free close to the Italian border, in the Nova Gorica-Monfalcone area.

They were registered by the police in Monfalcone, had train tickets provided, and were sent to the refugee camp in the Italian city of Latina, close to Rome.

“Following the inquiry conducted by a four or five people committee, I got my political refugee status based on the documents that proved my time in the prison at Gherla”, he says.

He was accepted by Canada, to emigrate with the status of “voluntary exile.” A new life was awaiting him on the new continent.

An adventure for the whole family

Between 1984 and 1989, Stăuceanu came back to Romania four times – the trips were mentioned in his Securitate file, now held by the CNSAS. He was under close surveillance both in Montreal, Canada, where he settled, and in Romania. His trips aimed at legally getting out of the country his brother and his brother’s family, who were living in Lugoj, Timiş County.

After five years of failed attempts, Stăuceanu went on a hunger-strike in front of the Romanian Embassy in Ottawa. He started it on September 25, 1989, and stopped ten days later, when he got the approval for his brother to leave Romania, accompanied by his own family. On December 5, 1989, they all arrived to Canada.

Stăuceanu’s fights for a legal precedent

Stăuceanu took the Romanian State to court. He filed two actions with the Suceava Tribunal. One with the Civil Court, under Law 221/2009, which deals with the political convictions inflicted between 1945 and 1989; the file number is 3675/86/2014; the second action he filed was with the Administrative Court, against the public institution responsible to make financial reparations to the victims of political trials during communism; the file number is 4811/86/2014.

The ruling on the latter was suspended until the Supreme Court of Justice will rule on the appeal to his first civil action, which is now under consideration by this court, as file number 254/39/2015.

Stăuceanu hopes the ruling in his case would serve as a legal precedent for other former border-jumpers to use. The court of first instance agreed that his conviction as a criminal according to the ruling 158, made public on May 23, 1975 by the Oraviţa Court, was in fact politically motivated. But the financial compensation is still pending a ruling from the Supreme Court.

“I felt I had to leave that communist State at all costs; it imposed on its citizens a life-style I could not agree with: mendacity in all aspects of life, and the personality cult for dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. I understood, early on in life, that we were all inhabiting a large prison cell, called the Socialist Republic of Romania”, Stăuceanu says.