Framing the past: How Roma people are depicted in Romanian and Greek schools

The way it is represented in formal education tells a lot about the condition of a people. Even when it is present in textbooks in South Eastern Europe, the history of the Roma is often ignored or represented in a way that perpetuates stereotypes and misconceptions

Framing-the-past-How-Roma-people-are-depicted-in-Romanian-and-Greek-schools

Athens library - ©katatonia82/Shutterstock

The so-called “stateless people”, originally migrated from northern India to Europe in the 14th century, today they are officially referred to as “Roma” and “Travellers”, two umbrella-terms adopted by the Council of Europe to embrace a wide range of ethnic groups, divided as follows: Roma, Sinti/Manush, Calé, Kaale, Romanichals, Boyash/Rudari; Balkan Egyptians (Egyptians and Ashkali), Eastern groups (Dom, Lom and Abdal); Travellers, Yenish, populations referred to as “nomads”, and persons that identify themselves as “Gypsies”.

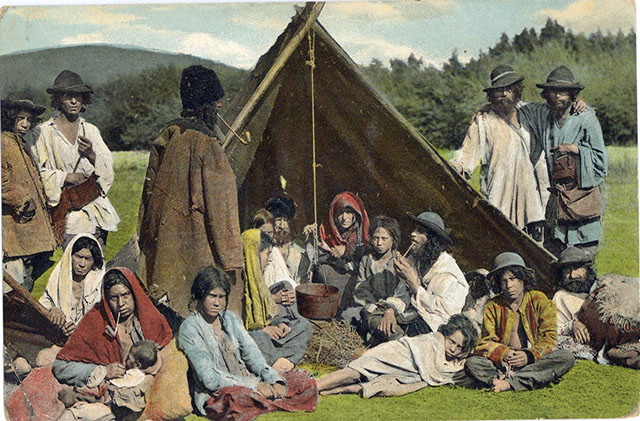

The history of the Roma in Europe is one of suffering. For centuries, many were enslaved by noble families and states, until slavery was finally abolished in the 19th century. But freedom never meant equality. Forced assimilation, violent expulsions, and the horrors of the Holocaust – in which between 220,000 and 1.5 million Roma lost their lives – left deep scars. Roma continued to face systematic discrimination after World War II, yet their vibrant cultural heritage in music, dance, and storytelling endures. Today, the Roma community continues its struggle for equal rights and recognition.

What do Romanian history textbooks say about the Roma people?

During the communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu there were almost no reference to Roma in school textbooks. In an attempt to promote a unified national identity, centered on ethnic Romanians, the experiences and contributions of the Roma, as well as other minorities, were left out of history books. This exclusion was intentionally designed to downplay ethnic diversity and foster a monolithic version of Romanian identity. The aim of assimilationist policies was to push Roma communities to abandon their cultural practices, reinforcing their invisibility in official discourse and perpetuating old stereotypes and discriminations that still persist.

After the fall of communism, Romania’s education system was affected by the slow transition to democracy, marked by continuos reforms and frequent changes. In the years of transition, the tendency of the individual to turn to his or her own ethnic group led to the process of social categorization on an ethnic basis, determining further discrimination.

Today, the Romanian Ministry of Education oversees multiple textbook options for each subject. The offer is very varied in terms of quality and approach: while some textbooks remain focused on traditional narratives, others include more modern, inclusive perspectives. Teachers, in principle, can choose the books they consider most suitable for their students. The freedom of choice is very welcome, but this flexibility leads to some inconsistencies.

The Highschool history textbook (Gimnasium edition), published in 2007, was one of the first schoolbooks to mention the slavery of the Roma, but it addressed the issue through stereotypes, linking the position of the Roma to their “backwardness”.

“Since their arrival in these lands – the book states – the Roma were considered an inferior people because of their backward lifestyle and physical appearance. Therefore, from the very beginning, they were marginalized and isolated”. This narrative implicitly blames Roma communities for their treatment throughout history.

It has taken time to develop more realistic perspectives in history teaching. Only in 2020 have some more comprehensive textbooks been published, but many of them still present a biased perspective, maintaining nationalist tones and downplaying the experience of slavery and the Holocaust. This selective revisiting highlights the ongoing challenge of promoting balanced narratives in education.

Today, high school students in Romania learn from a textbook (ART edition) that “enslaved” Roma lived in poverty, practicing their trades and maintaining their traditional lifestyle. This description, taken out of context, reflects prejudices and risks leading to generalizations. One of the exercises in the book asks students to organize "a debate about the impact of prejudices on a community". Although it addresses the issue of prejudice, the exercise is reductive, ignores the impact of slavery and avoids critical reflections that foster true historical understanding.

Another textbook (published by CD Press) speaks of the Roma in the Middle Ages as people "subjected to all forms of injustice and abuse by their masters”, but claims that the Roma "lived among Romanians, integrated into medieval society".

As for the Roma Holocaust, we read (Niculescu’s textbook version) that “many were deported, some of them died because of the detention regime”. The textbooks do not provide more details that could facilitate a better understanding of the historical context.

Addressing Roma history is not only about slavery, deportation and genocide, but also about giving visibility to those who have overcome these traumas. As Luiza Medeleanu, an expert in intercultural education, suggests , Romanian students should learn more about people like Anna Frank, but also Constantin Anica, a young Roma Holocaust survivor, in order to foster empathy and dialogue.

However, as history teacher Ioan Cristian Caravană points out, history taught in Romanian schools is still “an official history, to be learned by heart. Rather than encouraging critical thinking, lessons present a pre-established narrative that limits deeper understanding”. Discussing historical phenomena, like racism, would allow us to understand their persistence, helping to break the vicious circle of social exclusion. School is the best place to tell meaningful stories and initiate debates, also to encourage Roma teenagers to deeply understand their roots and history and increase their self-esteem.

For Vintilă Mihăilescu, renowned Romanian anthropologist, history education deeply impacts students’ sense of belonging. When textbooks focus only on Romanian heroes, ignoring the history of Roma people, they risk sending Roma students a negative message, making them feel excluded. Mihăilescu believed in promoting critical thinking, urging students to ask difficult questions and address all aspects of their national history, including uncomfortable issues that challenge traditional narratives.

Specifically, focusing on the history of the Roma people, one should:

– acknowledge the centuries of slavery that Roma endured in Romanian territories, a historical fact often belittled or ignored in textbooks

– talk about the Holocaust, during which approximately 25,000 Roma were deported, many died under the Antonescu regime

– highlight the persistent discrimination and systematic exclusion that Roma have faced in the post-communist era

Despite the significant progress made by the education system since the fall of communism, in Romania teaching the history of the Roma people is still optional, leaving teachers the choice of whether or not to delve into the topic.

The case of Greece

The first references to Roma populations in the region of Peloponnese date back to the 14th century. Although there is no academic consensus on the routes and circumstances of Roma migration, it is assumed that their arrival is a consequence of migratory waves towards central Europe, the Balkans and Greece – mainly in the regions of Thrace and Macedonia – conditioned by the gradual expansion of Ottoman rule to the territories of the Byzantine Empire at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century culminated with the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Despite their long presence in Greece, Roma acquired political rights only in the 1970s. The first mapping of Roma communities was carried out in 1996 (Vassiliadou & Pavli Korre 2011; Μarkou 2013:132). According to 2021 data provided by the General Secretariat of Social Solidarity and Combating Poverty, the Roma population in the country amounts to 117,495 permanent residents and constitutes 1.13% of the total population. The majority of Greek Roma are Orthodox.

According to the UNICEF office in Greece, Roma are still a vulnerable minority, facing difficulties in accessing housing, health, education and employment. Over the last decades, the Hellenic Ministry of Education has launched several initiatives to combat illiteracy and delinquency among the Roma communities. Since the 1990s, several Greek universities have launched pilot programs with an ambitious goal: bring Roma children from the streets and child labor into schools (Skourtou 2003: 98). Specifically, since 2015, the state has promoted several extracurricular courses for Roma children, similar to those designed in 2016-2017 to meet the needs of refugee children in Greek schools (Drosopulos 2018).

In a study published in 2022, Eleni Mousena, Georgia Aggelidou and Anastasia Vasilopoulou observe that “a large part of the educational community believes that the causes of Roma children dropping out of school are related to their families’ negative attitude towards school and education, while the parents of Roma children are unhappy with teachers and the educational system”. The reasons why Roma children feel excluded from the national school system are mainly related to the absence of any reference to Roma in textbooks, but also to the general attitude of Greeks who perceive Roma as “others”, problematic people living on the margins of the society.

Otherness, exoticismandpseudo–interculturalism

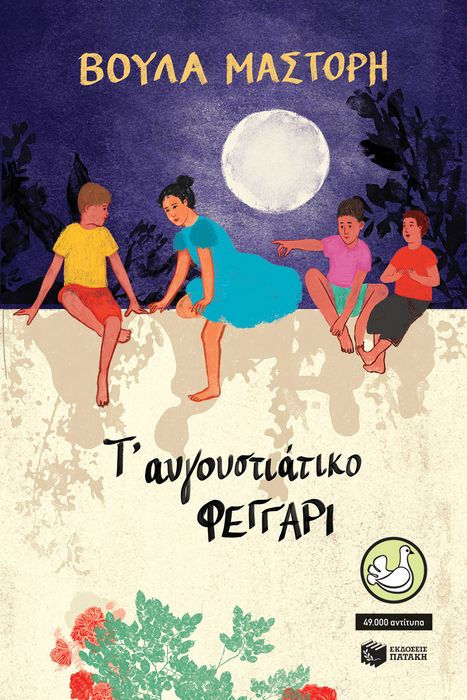

August Moon by Voula Mastori is one of the classics of post-war Greek children’s literature, a title traditionally included in “reading lists” distributed to students before the Christmas and Easter holiadys. Published in thousands of copies by Patakis, one of the most prominent publishing houses in Greece, the book tells the story of a young tomboy who attends the last grade of primary school in a suburb. With her anticonformist behaviour, the protagonist raises concerns in conservative society: she becomes friends with a young tinsmith, a Roma whom the children from the neighborhood fear and from whom they run away. The presence of male character who, contrary to popular belief, is neither a thief nor a child abductor, is one of the “less negative” references to “Gypsie” in Greek children’s literature, that has preserved, if not even reinforced stereotypical and discriminatory representations of the Roma people (Gotovos 2004: 7).

As for the history and fiction books used in schools, references to Roma culture are completely absent. The Roma people and their language are only briefly mentioned in the drama books for the last classes of primary school. However, these are incomplete and quite conventional references.

Aggelos Hatzinikolaou is a retired primary school teacher. Having spent most of his career teaching in Dendropotamos, the most notorious ghetto in Thessaloniki, inhabited almost exclusively by Roma, he has developed a deep understanding of Roma culture in the Greek context. Interviewed by OBCT, he comments on the ethnocentric nature of the Greek school system, where any reference to cultures that deviate from the dominant norm is superficial and usually limited to folkloristic elements.

“In the name of supposedly promoting multiculturalism, as expected in our globalized societies, there have been superficial attempts to ‘include’ populations considered as ‘others’, such as Roma, migrants and refugees. However, an intercultural dialogue cannot be achieved by stereotypical references to food, dance and songs, as is usually the case. There needs to be a much deeper dialogue, which is lacking in our education system”.

Late professor Sofia Gavriilidis has conducted important academic work in the field of pedagogy, illustrating examples of “pseudo-intercultural” books for children, both in formal education and in literature. “Pseudo-interculturalism” refers to attempts to acknowledge other cultures, but in ways that either exoticize the ”other”, further emphasizing differences rather than building bridges through shared traits, or imply the superiority of the dominant culture by depicting “others” as “victims”, in the same way that refugees and migrants are associated exclusively with war, trauma, poverty and other negative phenomena.

Georgia Kalpazidou is an activist, writer and co-founder of the NGO R.E.V.M.A. NGO (Roma Educational Vocational Maintainable Assistance), based in Ampelokipoi-Menemeni, in Northern Greece. PhD candidate in linguistics and member of the Roma community, Georgia has been mentoring young girls in accessing education. Driven by the desire to fill a gap in Greek children’s fiction, the young writer has published a children’s picture book about early school leaving among Roma children. When asked about the presence of Roma culture in textbooks, her answer confirmed the above-mentioned trend

“This is an interesting issue, I have also studied it, coming to the conclusion that there are no references, apart from some stereotypical (although not necessarily negative) images that students can come across when reading fiction books. So it is up to the teachers to decide whether to delve into the topic or not, formal schoolbooks do not contain any indication in this regard”.

In conclusion, juxtaposing the cases of two countries in South Eastern Europe, Romania and Greece, it seems that today more than ever representing history in schoolbooks is a complex challenge. It is not just about dates and events, but also about including voices, facing uncomfortable truths, and dismantling outdated perspectives. Although the history of the Roma people is marked by hardship and resilience, from enslavement to surviving the Holocaust, this reality is often belittled or misrepresented in textbooks. This raises a difficult but necessary question: how to teach history that truly reflects everyone’s experiences?

This publication has been produced within the Collaborative and Investigative Journalism Initiative (CIJI ), a project co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa and do not reflect the views of the European Union. Go to the project page

Tag: CIJI

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Framing the past: How Roma people are depicted in Romanian and Greek schools

The way it is represented in formal education tells a lot about the condition of a people. Even when it is present in textbooks in South Eastern Europe, the history of the Roma is often ignored or represented in a way that perpetuates stereotypes and misconceptions

Framing-the-past-How-Roma-people-are-depicted-in-Romanian-and-Greek-schools

Athens library - ©katatonia82/Shutterstock

The so-called “stateless people”, originally migrated from northern India to Europe in the 14th century, today they are officially referred to as “Roma” and “Travellers”, two umbrella-terms adopted by the Council of Europe to embrace a wide range of ethnic groups, divided as follows: Roma, Sinti/Manush, Calé, Kaale, Romanichals, Boyash/Rudari; Balkan Egyptians (Egyptians and Ashkali), Eastern groups (Dom, Lom and Abdal); Travellers, Yenish, populations referred to as “nomads”, and persons that identify themselves as “Gypsies”.

The history of the Roma in Europe is one of suffering. For centuries, many were enslaved by noble families and states, until slavery was finally abolished in the 19th century. But freedom never meant equality. Forced assimilation, violent expulsions, and the horrors of the Holocaust – in which between 220,000 and 1.5 million Roma lost their lives – left deep scars. Roma continued to face systematic discrimination after World War II, yet their vibrant cultural heritage in music, dance, and storytelling endures. Today, the Roma community continues its struggle for equal rights and recognition.

What do Romanian history textbooks say about the Roma people?

During the communist regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu there were almost no reference to Roma in school textbooks. In an attempt to promote a unified national identity, centered on ethnic Romanians, the experiences and contributions of the Roma, as well as other minorities, were left out of history books. This exclusion was intentionally designed to downplay ethnic diversity and foster a monolithic version of Romanian identity. The aim of assimilationist policies was to push Roma communities to abandon their cultural practices, reinforcing their invisibility in official discourse and perpetuating old stereotypes and discriminations that still persist.

After the fall of communism, Romania’s education system was affected by the slow transition to democracy, marked by continuos reforms and frequent changes. In the years of transition, the tendency of the individual to turn to his or her own ethnic group led to the process of social categorization on an ethnic basis, determining further discrimination.

Today, the Romanian Ministry of Education oversees multiple textbook options for each subject. The offer is very varied in terms of quality and approach: while some textbooks remain focused on traditional narratives, others include more modern, inclusive perspectives. Teachers, in principle, can choose the books they consider most suitable for their students. The freedom of choice is very welcome, but this flexibility leads to some inconsistencies.

The Highschool history textbook (Gimnasium edition), published in 2007, was one of the first schoolbooks to mention the slavery of the Roma, but it addressed the issue through stereotypes, linking the position of the Roma to their “backwardness”.

“Since their arrival in these lands – the book states – the Roma were considered an inferior people because of their backward lifestyle and physical appearance. Therefore, from the very beginning, they were marginalized and isolated”. This narrative implicitly blames Roma communities for their treatment throughout history.

It has taken time to develop more realistic perspectives in history teaching. Only in 2020 have some more comprehensive textbooks been published, but many of them still present a biased perspective, maintaining nationalist tones and downplaying the experience of slavery and the Holocaust. This selective revisiting highlights the ongoing challenge of promoting balanced narratives in education.

Today, high school students in Romania learn from a textbook (ART edition) that “enslaved” Roma lived in poverty, practicing their trades and maintaining their traditional lifestyle. This description, taken out of context, reflects prejudices and risks leading to generalizations. One of the exercises in the book asks students to organize "a debate about the impact of prejudices on a community". Although it addresses the issue of prejudice, the exercise is reductive, ignores the impact of slavery and avoids critical reflections that foster true historical understanding.

Another textbook (published by CD Press) speaks of the Roma in the Middle Ages as people "subjected to all forms of injustice and abuse by their masters”, but claims that the Roma "lived among Romanians, integrated into medieval society".

As for the Roma Holocaust, we read (Niculescu’s textbook version) that “many were deported, some of them died because of the detention regime”. The textbooks do not provide more details that could facilitate a better understanding of the historical context.

Addressing Roma history is not only about slavery, deportation and genocide, but also about giving visibility to those who have overcome these traumas. As Luiza Medeleanu, an expert in intercultural education, suggests , Romanian students should learn more about people like Anna Frank, but also Constantin Anica, a young Roma Holocaust survivor, in order to foster empathy and dialogue.

However, as history teacher Ioan Cristian Caravană points out, history taught in Romanian schools is still “an official history, to be learned by heart. Rather than encouraging critical thinking, lessons present a pre-established narrative that limits deeper understanding”. Discussing historical phenomena, like racism, would allow us to understand their persistence, helping to break the vicious circle of social exclusion. School is the best place to tell meaningful stories and initiate debates, also to encourage Roma teenagers to deeply understand their roots and history and increase their self-esteem.

For Vintilă Mihăilescu, renowned Romanian anthropologist, history education deeply impacts students’ sense of belonging. When textbooks focus only on Romanian heroes, ignoring the history of Roma people, they risk sending Roma students a negative message, making them feel excluded. Mihăilescu believed in promoting critical thinking, urging students to ask difficult questions and address all aspects of their national history, including uncomfortable issues that challenge traditional narratives.

Specifically, focusing on the history of the Roma people, one should:

– acknowledge the centuries of slavery that Roma endured in Romanian territories, a historical fact often belittled or ignored in textbooks

– talk about the Holocaust, during which approximately 25,000 Roma were deported, many died under the Antonescu regime

– highlight the persistent discrimination and systematic exclusion that Roma have faced in the post-communist era

Despite the significant progress made by the education system since the fall of communism, in Romania teaching the history of the Roma people is still optional, leaving teachers the choice of whether or not to delve into the topic.

The case of Greece

The first references to Roma populations in the region of Peloponnese date back to the 14th century. Although there is no academic consensus on the routes and circumstances of Roma migration, it is assumed that their arrival is a consequence of migratory waves towards central Europe, the Balkans and Greece – mainly in the regions of Thrace and Macedonia – conditioned by the gradual expansion of Ottoman rule to the territories of the Byzantine Empire at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century culminated with the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Despite their long presence in Greece, Roma acquired political rights only in the 1970s. The first mapping of Roma communities was carried out in 1996 (Vassiliadou & Pavli Korre 2011; Μarkou 2013:132). According to 2021 data provided by the General Secretariat of Social Solidarity and Combating Poverty, the Roma population in the country amounts to 117,495 permanent residents and constitutes 1.13% of the total population. The majority of Greek Roma are Orthodox.

According to the UNICEF office in Greece, Roma are still a vulnerable minority, facing difficulties in accessing housing, health, education and employment. Over the last decades, the Hellenic Ministry of Education has launched several initiatives to combat illiteracy and delinquency among the Roma communities. Since the 1990s, several Greek universities have launched pilot programs with an ambitious goal: bring Roma children from the streets and child labor into schools (Skourtou 2003: 98). Specifically, since 2015, the state has promoted several extracurricular courses for Roma children, similar to those designed in 2016-2017 to meet the needs of refugee children in Greek schools (Drosopulos 2018).

In a study published in 2022, Eleni Mousena, Georgia Aggelidou and Anastasia Vasilopoulou observe that “a large part of the educational community believes that the causes of Roma children dropping out of school are related to their families’ negative attitude towards school and education, while the parents of Roma children are unhappy with teachers and the educational system”. The reasons why Roma children feel excluded from the national school system are mainly related to the absence of any reference to Roma in textbooks, but also to the general attitude of Greeks who perceive Roma as “others”, problematic people living on the margins of the society.

Otherness, exoticismandpseudo–interculturalism

August Moon by Voula Mastori is one of the classics of post-war Greek children’s literature, a title traditionally included in “reading lists” distributed to students before the Christmas and Easter holiadys. Published in thousands of copies by Patakis, one of the most prominent publishing houses in Greece, the book tells the story of a young tomboy who attends the last grade of primary school in a suburb. With her anticonformist behaviour, the protagonist raises concerns in conservative society: she becomes friends with a young tinsmith, a Roma whom the children from the neighborhood fear and from whom they run away. The presence of male character who, contrary to popular belief, is neither a thief nor a child abductor, is one of the “less negative” references to “Gypsie” in Greek children’s literature, that has preserved, if not even reinforced stereotypical and discriminatory representations of the Roma people (Gotovos 2004: 7).

As for the history and fiction books used in schools, references to Roma culture are completely absent. The Roma people and their language are only briefly mentioned in the drama books for the last classes of primary school. However, these are incomplete and quite conventional references.

Aggelos Hatzinikolaou is a retired primary school teacher. Having spent most of his career teaching in Dendropotamos, the most notorious ghetto in Thessaloniki, inhabited almost exclusively by Roma, he has developed a deep understanding of Roma culture in the Greek context. Interviewed by OBCT, he comments on the ethnocentric nature of the Greek school system, where any reference to cultures that deviate from the dominant norm is superficial and usually limited to folkloristic elements.

“In the name of supposedly promoting multiculturalism, as expected in our globalized societies, there have been superficial attempts to ‘include’ populations considered as ‘others’, such as Roma, migrants and refugees. However, an intercultural dialogue cannot be achieved by stereotypical references to food, dance and songs, as is usually the case. There needs to be a much deeper dialogue, which is lacking in our education system”.

Late professor Sofia Gavriilidis has conducted important academic work in the field of pedagogy, illustrating examples of “pseudo-intercultural” books for children, both in formal education and in literature. “Pseudo-interculturalism” refers to attempts to acknowledge other cultures, but in ways that either exoticize the ”other”, further emphasizing differences rather than building bridges through shared traits, or imply the superiority of the dominant culture by depicting “others” as “victims”, in the same way that refugees and migrants are associated exclusively with war, trauma, poverty and other negative phenomena.

Georgia Kalpazidou is an activist, writer and co-founder of the NGO R.E.V.M.A. NGO (Roma Educational Vocational Maintainable Assistance), based in Ampelokipoi-Menemeni, in Northern Greece. PhD candidate in linguistics and member of the Roma community, Georgia has been mentoring young girls in accessing education. Driven by the desire to fill a gap in Greek children’s fiction, the young writer has published a children’s picture book about early school leaving among Roma children. When asked about the presence of Roma culture in textbooks, her answer confirmed the above-mentioned trend

“This is an interesting issue, I have also studied it, coming to the conclusion that there are no references, apart from some stereotypical (although not necessarily negative) images that students can come across when reading fiction books. So it is up to the teachers to decide whether to delve into the topic or not, formal schoolbooks do not contain any indication in this regard”.

In conclusion, juxtaposing the cases of two countries in South Eastern Europe, Romania and Greece, it seems that today more than ever representing history in schoolbooks is a complex challenge. It is not just about dates and events, but also about including voices, facing uncomfortable truths, and dismantling outdated perspectives. Although the history of the Roma people is marked by hardship and resilience, from enslavement to surviving the Holocaust, this reality is often belittled or misrepresented in textbooks. This raises a difficult but necessary question: how to teach history that truly reflects everyone’s experiences?

This publication has been produced within the Collaborative and Investigative Journalism Initiative (CIJI ), a project co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa and do not reflect the views of the European Union. Go to the project page

Tag: CIJI