© Caiete de rețete

Anthropologist Anca Danilă is the creator of the project Caiete de rețete (Recipe Notebooks), launched in Bucharest two years ago, which aims to collect family recipe books, archive them in a digital database and thus protect a precious heritage

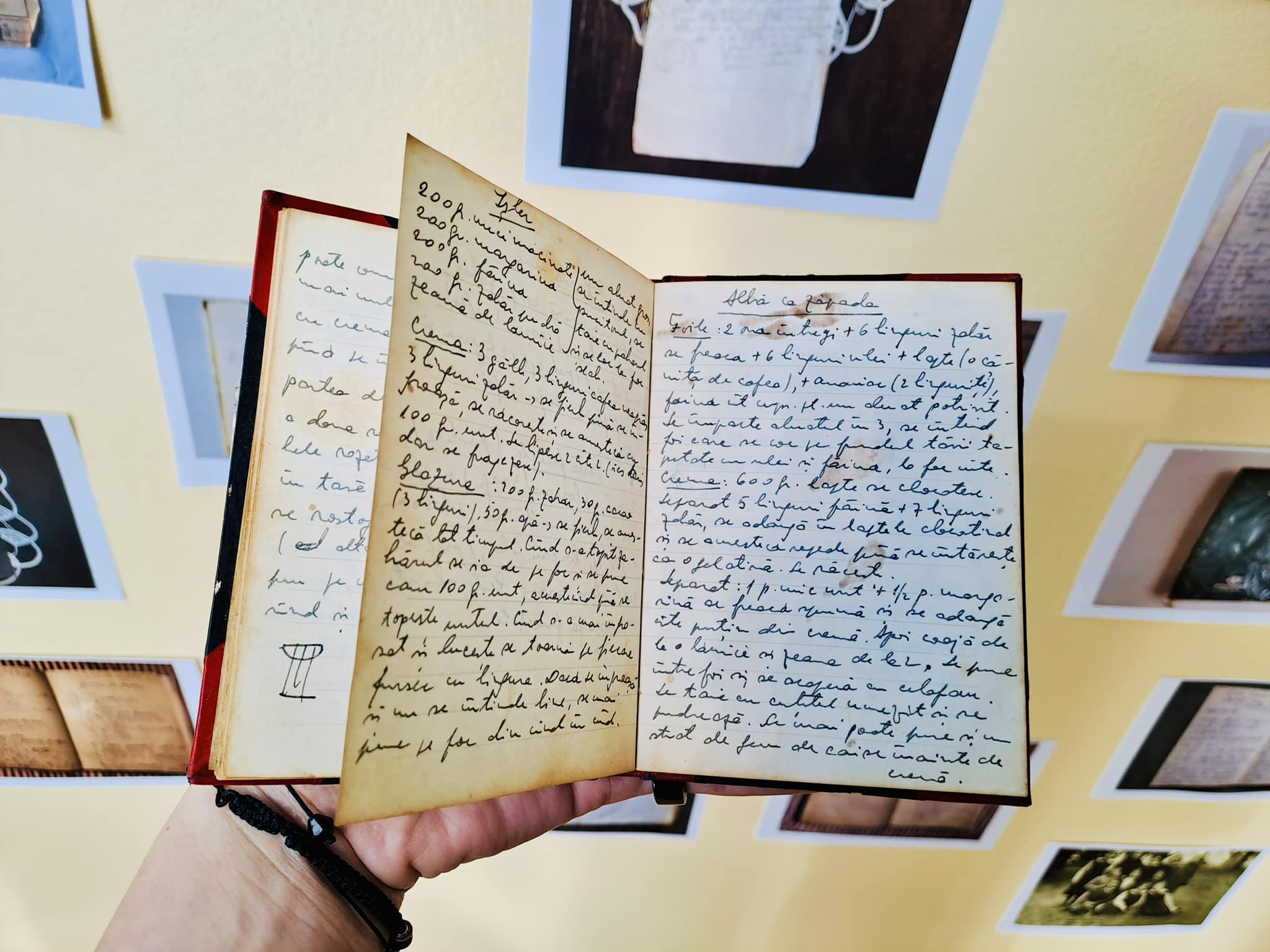

For generations, pen and paper have been the means to preserve memory: out of necessity, for pleasure or simply for the desire to pass something on to those who will come after. Historical documents, stories, personal diaries, but also notebooks of cooking recipes. Since 2022, the project “Recipe Notebooks”, born in Bucharest, Romania, has aimed to collect family recipe books, archive them in a digital database and thus protect a precious treasure that tells of our past. A past that deserves life.

To date, the project has managed to digitise and publish over 70 recipe books. Anca Danilă shared with us curious and funny details about how this initiative works.

Anca, was it you who had the idea for this project? It seems fantastic to me, also thinking about the recipe notebook I have at my mother's house and the emotions and nostalgia it arouses in me every time I see it.

The idea, in fact, was not only mine. Indeed, I bet – and I am sure of this also from experience – that many people have felt the desire to do something with these recipe books that are true pieces of history on the verge of being lost. In the end, however, I was simply the only one in our country to put the idea into practice.

At 33, I started studying Ethnology, and one of my professors told us during a seminar that we have to change something in the world, stopping thinking that everything belongs to us, as if it were always there, at our disposal without conditions. When I returned to my parents' house, I saw my mother with her recipe book in her hands and I had this epiphany. I had never noticed it before: that recipe book had always been there, but I had never really understood its meaning… They say that every woman is a mother at least for the time of one recipe. This is the heart of the project; that's exactly how it started. When I returned to Bucharest, I started the project.

At the beginning it was just ancadanila.ro, and I worked on it together with two colleagues. Then everything remained a bit pending, until I met the anthropologist Ionuţ Dulămiţă. I owe him the real development of the project, because he was the one who insisted that we try to make three applications for funding, with the idea that, in this way, at least one would be successful. And in the end we got all three. Fantastic!

Indeed, funding is often an issue. What kind of funding have you received?

Public funds. I have to say that, ironically, these are sometimes easier to obtain. There are not many, but they offer more possibilities. You present a proposal and the doors are much more open than with private funding. In private funding, on the other hand, what you have already done in the past counts a lot - sometimes too much. They want to see the experience you bring and also get a certain return on the project. This is why I can say that public funding is a great opportunity, especially for those in the cultural sector who want to start an initiative from scratch.

Speaking of an initiative from scratch, how did you make yourselves known? How do the notebooks reach you?

Here is another advantage of public funding: each type of funding also includes promotional activities. There are specially organised events, contacts with the press and dedicated press releases. For example, we received funding from the municipality of Brașov, and right in Brașov, in Astra Square, we set up a small stand with photos of the notebooks we had already collected. It was the ideal place to meet the people we were looking for: the market is a space that unites people of all ages and social backgrounds. In addition, the recipe notebooks reflect seasonality, just like the market itself.

We really spread the word at the market. People found out that we are the only ones in Romania doing this, so they shared the news and came to visit us.

There must be a specific way of storing the notebooks, a procedure that you follow...

Yes, of course. The truth is that many people interested in this project fear that they will have to give up their notebooks and leave them with us. But that is not the case at all: we do not take the notebooks. Instead, we ask for photos or scans. We have a document that lists all the steps to follow, with details on the quality of the images and more. The “child” of the family – who is often someone in their 40s or 50s or even older – takes the photos under our guidance and, ideally, also writes a story page for us about the family’s connection to the notebook. We publish the file on our website caietederete.ro along with its story. We also have documentary videos that delve into some of the stories in the form of dialogues with the people involved.

It must be exciting to read all these stories and have direct contact with the people who tell them. From an anthropological point of view, they say a lot about a culture, a country and the people who live there.

Yes… The fieldwork is really exciting. The women – because they are mainly the ones who write the notebooks – were virtually invisible, and yet, in the end, they were true chroniclers of their times, authors of authentic fragments of memory.

If you look at a notebook that goes from the 40s to the 90s, you will see different stages of history. The poverty of the post-war period, then a period of relative abundance, visible from the ingredients used. The vanilla bean, for example, is a sign of prosperity. Then, with the arrival of communism in Romania, the recipes reflect other changes: the notebook is no longer just an object reserved for those who knew how to write, but becomes accessible to everyone, thanks to mass literacy. You can feel an entire population in the midst of an industrial revolution, with migration from the countryside to the city, and the notebooks show the adaptation of the older generations to the new reality. At the same time, you can sense the poverty of the communist regime because simple, survival recipes appear: butter disappears and margarine arrives, rich creams are replaced with great creativity to cope with the lack of ingredients. And you can once again notice the seasonality of the ingredients, an element that we perceive much less today.

On a personal level, reading a notebook, you realise if a woman was an expert in the kitchen or if she was a beginner, due to the level of elaboration and detail in the instructions. From there you can even infer something about the family situation. Sometimes you can even understand when a child has arrived in the family, because the type of recipes changes to adapt to new needs.

I bet that sweets are more present...

Yes, or healthier recipes appear. At a certain point, you can even understand that it is the child themselves who writes, for various reasons: to involve them in an activity in the kitchen or to teach them something...

Or simply to have them practice writing, just like it happened to me.

Yes! Surely also for this. You can clearly see when children write: the mistakes, the embarrassment, the insecurity of those who write, erase and correct. Beautiful, of an incredible purity!

Is there a cookbook, a recipe or a story that has particularly struck you?

As an anthropologist, I am very interested in reconstructing pieces of history and going beyond the recipes themselves. I remember a notebook from 1912, probably belonging to a chef from Bucovina, in northern Romania. It was full of delicious recipes, but above all written with the heart and with an extraordinary sense of humour.

Then, in a recipe from 1930 for the so-called "China Wine", among the ingredients you find 3 grams of cocaine. You realise that at the time it was available in pharmacies, while over time it has become one of the most devastating drugs. For me, recipes are witnesses to many aspects of our history and daily life. In notebooks you can still see oil stains, bits of dough dried out over time, drawings made absentmindedly, even bills and receipts forgotten between the pages. The notebook was a family object, of friends, a familiar flavour that united us. Today, however, cooking often has to do with variety. We constantly try to do new things, and the visual aspect has taken over. It is perhaps only during the holidays that we return to seek the familiar taste.

Do you think there are still people who write recipes in notebooks?

Maybe less than before, but yes, there are still people who do it. A volunteer from Brașov, for example, a girl of just 17, told me that, due to a food sensitivity, she started collecting her own recipes. Another person told me she keeps a recipe book for her mother, with dishes specially created for her dietary needs. If you think about it, even in the past, notebooks were born out of necessity, and they continue to be born for this reason. Some say that notebooks have become real family treasures, sometimes the subject of arguments. Of the three children, who will keep the notebook? Some have even stolen notebooks or torn pages to keep them for themselves.

In your opinion, is the recipe book a living tradition in other countries too? I think so, but have you ever had to deal with recipe notebooks outside of the Romanian space?

The cookbook is universal: wherever there is paper and pen, there it is. It is the same everywhere. It was born from the urge to write down, to remember, to pass on.

In the United States, for example, I have seen recipes that bear people's names, as happens in our country: the name of the person who personalised them (like "Dolce Ramona", for example). We recently received a notebook from North Macedonia and we tried to start collaborations with Portugal and Brazil. I would like to create a sort of franchising to expand the project's boundaries. In Italy, it would be interesting to investigate. Someone told me that there are family notebooks that are so precious that you can only get them through marriage, for example. They are not public, they are family heritage.

Speaking of franchising and the more practical aspects of the project, who is helping you at the moment and how is the initiative developing?

At the moment, it is mostly just me, with the support of the Cărturești Foundation. Cărturești is one of the most important bookshop chains in Romania. I want to continue promoting this initiative because I believe in it a lot. I also want to start a physical archive at the National Library of Romania, accessible to anthropologists, researchers or anyone interested. Finally, I firmly believe that recipe books deserve a special place in our calendars, so we are thinking of launching the National Recipe Book Day in Romania, or rather, the Days of December 22 and 23. It is especially at Christmas, in fact, that everywhere in the world people return to traditional flavours.

You mentioned tradition: having seen so many of these notebooks, do you really think that Romania has a traditional cuisine? I often hear people say: “Yes, but sarmale (meat and rice rolls) are Arab, moussaka is Greek, ciorba is almost Russian, and everyone makes polenta... what is typical for us?”

The issue becomes clear when we define the concept of tradition. For me, tradition is the result of this equation: context + time + custom = tradition. Following this formula, I can clearly say that yes, we have a traditional cuisine. It is not an original cuisine, but a mix. After all, cuisines have always met in some way. The way we took and adapted a recipe made it something different and, ultimately, something typical, ours.

I'm sure you're pursuing the project to preserve "something typical”, what belongs to us. But beyond that, what value do you think emerges? How do people react when you talk about it? Have you received any feedback?

At one point we launched a questionnaire, to which about 170 people responded, and I must say that it was really moving to read their comments. There are those who are not attached to family objects and do not attribute value to these notebooks, which sometimes get lost or thrown away. But those who recognise their value were so grateful. I met women who shed tears of emotion, because, for the first time in their lives, they felt important. Some were moved because a notebook from 1944 was the only object saved from the rubble of a bombed house. And some were inspired and created a recipe notebook to give to a friend for her wedding. In short, it is an initiative that pushes us to reflect, to explore the nuances of our family history.

I would like to see recipe books from all over the world, to demonstrate their universality through a common archiving effort. The recipe book is the love of one generation for another. We are the generation that can still hold these notebooks in our hands. What will we do with them? Here, let's pay homage to the past and to our families.

All the recipe books digitised so far are available on the website www.caietederete.ro , while those waiting for a new life can be sent to anca@caietederetete.ro

To Top

To Top