Turning an area of Belgrade into a Dubai of the Balkans. The Serbian government project for the right bank of the Sava, issued during the election campaign, appears unsustainable to critics

In Belgrade, on the right bank of the Sava river, there is a sizeable piece of land that seems to have been removed from the shaping force of urban planning. It is a large flat area, between the river and the rail-road tracks, for decades home to abandoned cars, some small industrial warehouse, and a procession of rusting relics – once a glorious boat – lying on the docks. Yet, it is from the 1950s that the amphitheatre of the Sava, this is its solemn name, inspires the imagination of architects, developers, and urban planners. Until now, however, all redevelopment projects have remained on paper.

Now it seems time for another try. The operation is called "Beograd na vodi", Belgrade on water. According to its promoter, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) led by ambitious Aleksandar Vučić, it is the largest development project ever conceived in the country. To achieve this, the government of Serbia chose a partner who, at least on paper, is up to the magnitude of the enterprise: Eagle Hills, a construction company for the United Arab Emirates, headed by tycoon Mohammed El- Abbar, who erected in Dubai Burj Khalifa, the current tallest building in the world.

“Belgrade on water” promises to revolutionize the Amphitheatre of the Sava by turning it into a cutting-edge area, equipped with futuristic architectural solutions worthy of the metropolis bordering the Persian Gulf. Over the entire surface (about 90 hectares) will rise residential buildings, offices, the largest shopping mall in the Balkans, schools, theatres, medical clinics, parks and gardens, luxury hotels, and a marina for yachts, all topped by a spectacular tower of 180m, the Belgrade Tower. The construction will take 5 to 7 years and a total investment of just under €3 billions. So say Vučić and El-Abbar, who presented to the public the mammoth project in mid-January.

Muddy waters

At the presentation, the promoters of Belgrade on the water sang in a unanimous chorus of praise and optimistic forecasts. Al-Abbar praised the project's ability to stimulate various sectors of the economy, especially tourism. According to Siniša Mali, president of the Belgrade's provisional city council, it will create about 200,000 jobs. Vučić went so far as to state that the project will enable the recovery of the Serbian economy and the country's exit from the crisis. In order to expedite the expropriation of land and the transfer of existing structures (the construction of a new railway station is planned), Belgrade on water should soon be declared a project of national interest.

The promoters of what has been called the "Manhattan of Serbia" have every incentive to proceed quickly with the approval of the project and the opening of the construction site. The general elections are close and Belgrade on the water is a good card to play in the election campaign. But some sectors of civil society do not like such a hurry. The Serbian chapter of Transparency International, for example, believes that the public has not been duly informed and complains that there has been no mention of a tender.

Indeed, the nature of the partnership agreement signed by the Government of Serbia with the construction company was not made very clear. It is not known, for example, whether it is a foreign investment or a credit agreement, which legal form the partnership has, who made the construction project and on the basis of which studies. But this is not an isolated case. Bypassing the usual bureaucratic procedures through a kind of 'fast track' for investment is an established practice in trade relations between Serbia and the UAE.

The Amphitheatre of the Sava, Belgrade's urban mixed blessing

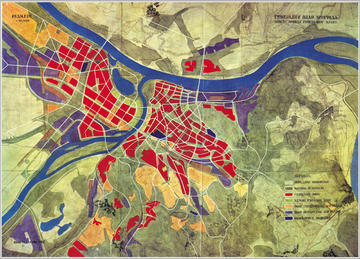

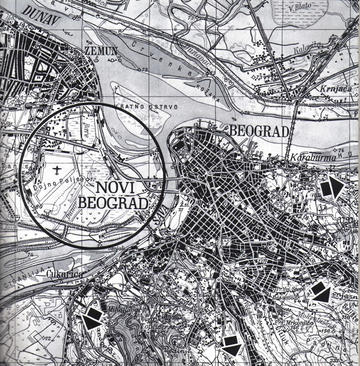

The Amphitheatre of the Sava was given its name by Russian architect Grigory Pavlović Kovaljevski, who arrived in Belgrade in the early 1920s, fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution. His project, included in Belgrade's General Urban Plan of 1923, involved the construction of residential and commercial buildings in the area next to the railway station. After the Second World War, the Amphitheatre was temporarily set aside, as all the creative energy of Serbian planners was catalysed by the construction of Novi Beograd, the 'ideal city' of socialist modernism. There was, however, a student who graduated in those years with a project on the Amphitheatre. His name was Ranko Radović, and later he became an established architect, professor of theory and construction techniques, and founder of the School of Architecture in Novi Sad.

The real breakthrough, however, came in the 1970s, with the adoption of the new General Urban Plan of Belgrade. A study by the Planning Committee indicates the Amphitheatre as the city's new cultural, tourist, and business centre, offering bold, colossal architectural solutions. Despite the positive opinion of the board, however, the plan will never be implemented. A decade later, in 1986, an international competition for the modernization of Novi Beograd gathers many proposals also involving the Amphitheatre, but once again the projects remain in the drawer.

At the end of the 1980s, the Planning Commission carries out the study "Varoš na vodi", hamlet on water. The idea is to build an artificial island, with buildings and tourist facilities, in the middle of the river Sava, and connect the two banks of the river with a network of canals and waterways. In 1995 came "Europolis", pet project of Milošević's Socialist Party in the election campaign for the 1996 local elections. The project was a compilation of pre-existing ideas and was never implemented.

How do you build the future?

Belgrade on water promises to put an end to an impressive series of failed attempts at urban renewal. But many are wondering if the operation really responds to the needs of Belgrade and its inhabitants. The association Ministarstvo prostora (Ministry of space), always sensitive to the issue of sustainable urban development, published a letter highly critical of the project.

The harshest passage reads: "We will transfer the railway and the bus station away from the city centre to make way for a marina for private yachts. We will build luxury hotels in hopes of becoming a global tourist destination. We will solve the problem of unemployment with temporary jobs in construction sites. We will build the largest shopping mall in the Balkans [...] when the existing ones have not been rented for years. We will build luxury apartments in a city where thousands of people have housing problems".

The letter ends with an invitation to reconsider the dominant paradigms of urban development. The Amphitheatre of the Sava, as well as many other areas of the city, could be the subject of a redevelopment strategy that privileges the public and the ecological dimensions. Only with this approach, reads the letter, can the city really "improve the quality of life of all the inhabitants of Belgrade, and make the city attractive to many more people, not only for owners of yachts on the Sava and the Danube".

But this is unlikely to be achieved as long as urban planning looks at the current electoral campaign rather than at the future of the city.

To Top

To Top