© ArtMari/Shutterstock

The National Library of Belgrade, the oldest cultural institution in Serbia, was destroyed on April 6, 1941 by the Axis forces on Hitler’s explicit orders. Thus Serbia lost an inestimable cultural heritage in a single day

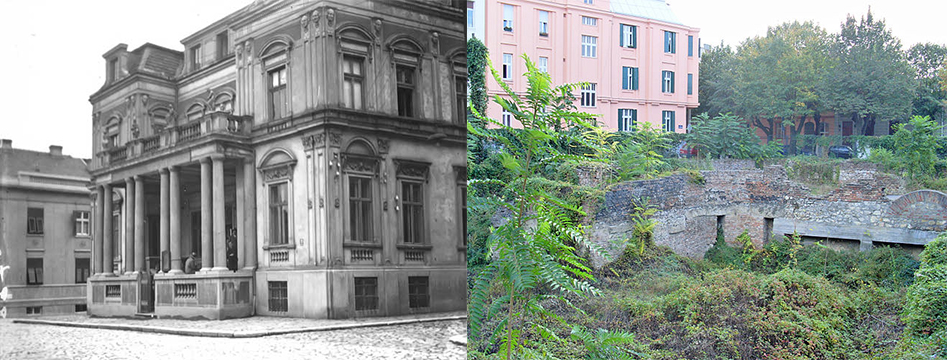

If, once the Covid 19 pandemic is over, you ever go to Belgrade, stop for a few minutes in Kosancicev Venac and, through an iron gate covered with climbing plants and weeds, observe the remains of the foundations of a building, or rather a hole. The only traces of life that can be seen there are those left by the occasional cat.

Until April 6, 1941 that place hosted the National Library, the oldest cultural institution in Serbia. It was founded in 1832 by a decree of Prince Milos Obrenovic (despite being illiterate and having an irascible character, the prince understood the purpose of the educated promoters of the proposal to establish the library).

I will briefly recall that the Axis forces attacked the Kingdom of Yugoslavia after the coup and popular protests of March 27 against the country's accession to the Tripartite Pact, decided two days earlier by the Cvetkovic-Macek government. The demonstrators shouted slogans: "Better a war than the Pact", "Better to die than to be slaves".

The Führer himself ordered that the National Library also be bombed. The failed painter was very, very angry with Yugoslavia, with the coup leaders, with Belgrade, and above all with the Serbs. The commander of Operation Punishment (the code name for the air strikes on Belgrade), General Alexander Löhr, spoke about it during the criminal trial against him that took place in Belgrade after the war. The general did not feel guilty, he believed that obedience to orders was a virtue, and during the trial his voice resembled that of a normal person. Among other things, he stated: "During the first attack we had to destroy the National Library, and only afterwards the objectives of military interest". When asked why they had decided to destroy the Library, the general replied: "Because that building housed what for centuries represented the cultural identity of that people".

We must not blame General Löhr too harshly, his "virtue" has not yet been eradicated, and we will talk about that "normality" later on.

German planes bombed Belgrade, then Kraljevo, Niš, and other cities. The attacks began without any formal declaration of war (some respectable historians argue that Operation Punishment affected the course of the war: Hitler was preparing to attack the USSR, but then suddenly lashed out at Yugoslavia; Operation Barbarossa was started two and a half months after the invasion of Yugoslavia and the advance of German tanks was slowed by the harsh Russian winter. The lesson to be learned: anger might delay you).

The first bombs fell on Belgrade at 06:30 on April 6, while most citizens were still sleeping. During the day, the planes threw themselves four times against the city, unloading incendiary bombs. Not even the columns of people fleeing the burning city were spared. The bombers took off from the airports of Vienna, Graz, and Arad. The capital of Yugoslavia was attacked again on April 11 and 12. 440 tons of bombs were dropped on the city.

The number of victims has never been precisely established. In the list of the dead in Belgrade, which at the time had 370,000 inhabitants, 2274 names appear, but some estimates speak of 4000 deaths. The city had suffered incalculable material damage: 714 buildings were completely destroyed, 1888 severely damaged, and 6829 damaged. The densely populated neighbourhoods, the railway station, the hospitals, the post office, the teachers' house, the Kalenic market, the Zemun airport were bombed. On the first day of the attack, hundreds of civilians were killed and injured in the courtyard of the Church of the Ascension, while several hundred people died in an air-raid shelter located in Karadorde park.

Also in the First World War

During the First World War, the Belgrade National Library was bombed by the Austro-Hungarian army. The building was evacuated three times and most of the book collection was saved. After the war, the National Library was moved to a neoclassical-style building located in Kosancicev venac 12, which until then housed the offices of Serbian entrepreneur and philanthropist Milan Vapa Where are the rich Serbian philanthropists today? What do they give up, what do they do for the common good? Of course, not counting the quid-pro-quos).

In 1941, the municipal administration and the management of the National Library, bearing in mind what had happened during the First World War, had planned to transfer the entire library fund to another location by April 10. The books, arranged in dozens of wooden boxes, were hit – according to the words of General Löhr – around 3:30 pm, "only in the third bomber attack". In the general chaos, no one had even tried to put out the fire. The last to catch fire were the most precious books kept in the underground deposit of the building, of which only that crater remains. Which, however, is distinguished from other craters. But we will also talk about this later.

The library catalogues were also lost in the fire, so the exact number of works burned is not known, but it is estimated that around 500,000 books, a collection of 1424 medieval manuscripts in Cyrillic, a collection of maps and graphics, some Ottoman documents concerning Serbia, an archive of newspapers and periodicals, and the entire correspondence of some leading exponents of Serbian and Yugoslav culture and politics were destroyed.

Subsequently, the collaborationist government forced the members of the commission in charge of drafting a report on the destruction of the National Library to blame the destruction on the local authorities, that allegedly behaved irresponsibly or underestimated the risks and treated superficially the question of the transfer of the library fund. Therefore, according to the collaborationist government, the main cause of the destruction of the book collection was not the bombing, but the inadequate protection of the books.

The fire lasted for several days. Fewer and fewer are the living witnesses to one of the greatest crimes against cultural heritage committed during the Second World War in Europe. In a single day, a people lost a priceless cultural heritage. All the memories of that day when the books were burned are identical: for a long time there was the smell of burnt paper, the wind scattered the ashes and bits of burnt paper everywhere. Of the entire library fund, only a collection of musical materials was saved, which in 1939 was lent to the Belgrade Academy of Music, and a medieval manuscript

New headquarters

In 1973 the National Library was moved to its new location in the Karadorde park. Germany had not contributed to the financing of the construction of the new building because Tito's Yugoslavia did not want to accept aid for the reconstruction of individual buildings, instead insisting on war reparations that encompassed different areas. "However, when the new library was inaugurated a few days later, also in 1973, the first foreign visitor was Willy Brandt, who brought with him a box full of books and that was the signal that Germany was aware of what had happened", recalls writer Ivan Ivanji, who for years was Tito's personal interpreter.

Germany had returned part of the books confiscated during the war to the National Library in Belgrade. Today Serbia and Germany collaborate intensively in the literary field. In 2011 Serbia was the guest of honour at the Leipzig Book Fair, while in 2017 Germany was the guest of honour at the Belgrade Book Fair. Thanks to the Traduki network, in recent years many books have been translated from German to Serbian and vice versa. The Goethe-Institut has been active in Belgrade for fifty years. When Ingo Schulze, one of the most important contemporary German writers, visited Belgrade, he gave a speech in the National Library. On that occasion, Schulze said he was honoured to have the opportunity to speak within an institution that had its old headquarters razed to the ground by the Nazis.

Writers can build bridges also over the abyss of oblivion, but only if, in addition to being writers, they are also men.

Sarajevo

August 25-26, 1992: the long night in which the books of the National Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina burned, bombed by the Serbs positioned in the hills around the besieged Sarajevo. "My people" were precise, General Löhr would surely have complimented them.

Ordered, executed. Obedience is a virtue.

The next day, in Italy… At that moment was I a traitor or rather a deserter? I don't know and I don't think too much about this dilemma, but that day I wrote, in one breath, a short text titled "Sarajevo, the bonfire of memories", published in the newspaper Il Manifesto. For some time now, that text has been part of my collection of short stories titled “The black holes of Sarajevo”. On one occasion, when asked if I would write that text again, I replied yes. To tell the truth, I would add that in 1992 the Serbian public television reported news on the Bosnian war accompanied by photographs of Sarajevo taken before the war began. I would also add that in fact the largest Serbian city in Bosnia was also attacked. And that in the Sarajevo Library, in addition to the books and documents belonging to the Bosnian, Croatian, and Jewish cultural, historical, and literary heritage, many Serbian books and documents were also lost (Ah, we don't need our past! We create the future, starting from scratch!). And that Bosnian Serb propaganda claimed that in Belgrade there was a copy of every single burnt book (like lies, propaganda has short legs). And that, with a few praiseworthy exceptions, all of Belgrade was silent.

A profound, profound silence.

Had Belgrade sunk into that hole in Kosancicev Venac? I know, I shouldn't ask this question. If Belgrade had really sunk into that hole, into that emptiness that still today – whether we want to admit it or not – acts as a warning, a terrifying and transnational warning, it would have felt empathy towards the Sarajevo people who that summer night in 1992 felt the same as the citizens of Belgrade in the spring of 1941, that is, they realised that not only the books were burning, not only the ashes were falling, and not only the "black birds" of the burnt paper flew, but something bigger, wider, and deeper was happening. Something greater than memory, wider than History in Motion, and deeper than ancient tragedies? Did 51 years, 4 months, and 20 days have to pass before the abyss of oblivion opened up in the conscience of a people? A huge chasm, as terrifying as those two million books lost and damaged in the fire that devoured Sarajevo's Vijecnica?

Fifteen years ago, on the occasion of the 65th anniversary of the bombing of the Belgrade National Library, well-known writer Svetlana Velmar Janković, then a member of the Library's Board of Directors, gave a speech. Part of her speech was then written on a sign hanging on that iron fence surrounding that hole: “Stop for a moment, you who are passing by! In this place until April 6, 1941 stood the National Library of Serbia. That day, early in the morning, the bombing of Belgrade began. First peace was wiped out and then the National Library in Kosancicev Venac was set on fire. For days they burnt the ancient written monuments, the old and new books, manuscripts and letters, documents and newspapers. For days the flames continued to destroy the evidence of the existence and history of a people. For days the fire devoured a centuries-old history summarised in written form. Then, finally, the flames turned to embers and the embers to ashes. In this place the ashes of most of the historical memory of the Serbian people are scattered. Therefore, stop for a moment, you who are passing by!”.

A moving text. Should I blame the writer for not mentioning Sarajevo? Sarajevo is never mentioned in political (and cultural) speeches during the commemoration of April 6. Is it easier to drink the water of the Lethe River? András Riedlmayer, a professor at Harvard University, also drank a couple of glasses while writing his essay “Genocide and books burnt at the stake in Bosnia ”. Citing all the book burnings in European history, he has forgotten the one that took place on April 6, 1941 in Belgrade. By pure chance? Or maybe Harvard is no longer what it used to be? However, the facts are irrefutable even when they are withheld.

And now, a little bit of light. Thanks to the many young artists and activists of various associations, including the members of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights – which since 2007 in Belgrade have been organizing a festival entitled "Days of Sarajevo" – it seems that awareness is growing of what happened during the fratricidal war in Bosnia and, more generally, during the nineties. For them, "discovering the truth" is more than a duty. They do not conceive of memory as something that expires quickly.

I leave you here. It is time you rested from this topic.

NB

This article is mostly based on the information contained in the following sources: the book "Kuca nesagorivih dusa: Narodna biblioteka Srbije 1838-1941" [The house of souls that do not burn: National Library of Serbia 1838-1941] by Dejan Ristic (Belgrade, 2019), the book "Narodna biblioteka Srbije u ratnim godinama (1941-1944)" [The National Library of Serbia in the war years 1941-1944] by Aleksandra Vranes (Belgrade, 2001), and the article "Mesta zlocina - mesta pomirenja: Narodna biblioteka Srbije "[Place of crime - place of reconciliation: the National Library of Serbia" by Sanja Klajic, published by Deutsche Welle, May 9, 2020)

To Top

To Top