The first book on the history of motoring in Serbia, and Yugoslavia, will soon be released. An interview with the author, Marko Miljković

You will soon publish the first scientific book about the history of motoring in Serbia and Yugoslavia. What will be your focus?

In my book Automobile is Freedom I have analysed the history of motoring in Serbia since 1903, the year when the first automobile appeared on the Belgrade streets. I approached the phenomenon of motoring from several different perspectives: automobile production, development of motor sport, construction of roads and other infrastructure. Taking into account the main idea of the book, that the automobile brought people more freedom than they could have ever dreamt, I wanted to analyse the development of personal and civil liberties in Serbian/Yugoslav society. Paradoxically or not, my analysis showed that in this respect Yugoslav society was “more free” in the period between the mid-1960s and the beginning of the 1980s, even though revisionists in Serbia today often speak of Yugoslavia as a “dungeon of nations”.

The Italian public only recently started to link Serbia to the Fiat. The perception is that this relation is something completely new, exclusively based on the search for cheap labor. But these connections are much deeper, are they not?

Over the entire history of mutual relationships Italy and Yugoslavia have always been close economic partners. In that sense, as one of the leaders of the Italian industry, the Fiat undoubtedly played an important role.

True cooperation started in 1954, when the Crvena Zastava factory (Kragujevac, Serbia) bought the licence for the production of several Fiat automobile models. The contract was signed on August 12, 1954 in Turin as one of the first great contracts of cooperation with the Western partners, and symbolically it represented the turning point in the development of the Yugoslav economy, marking a sort of an economic equivalent to the Yugoslav political breakup with the Soviet Union.

The most important year in the Yugoslav car production was 1955, when the Crvena Zastava started assembling the Fiat 600. In Yugoslavia this car was quickly nicknamed “fića”, or a “small Fiat”. Almost a million of “fića’s“ had rolled off the Crvena Zastava assembly lines by 1985, metaphorically putting Yugoslavs on the four wheels. “Fića“ has become a symbol of the modernization and success in the new socialist society, which was not only a family and police car, but also suitable even for long-distance journeys. Today, this car evokes strong emotions, and represents one of the main objects of the so-called “Yugo-nostalgia”.

Other Fiat models produced in the Crvena Zastava factory were also very popular. The famous milletrecento (Fiat 1300), known in Yugoslavia as “tristać”, owing to the comfort it had provided, became during the 1960s one of the favourite cars of the Yugoslav socialist elite. Sometimes it was even called “the Yugoslav Mercedes”.

How important was cooperation with the Fiat for the development of Yugoslav economy?

Cooperation with the Fiat was one of the most important government projects in Yugoslavia, since the automobile industry was one of the leading sectors of the Yugoslav industrialization after the Second World War. The only problem in these ambitious plans was that Yugoslavs had no previous experience in the car production, and they simply had no idea how to do that. Mass production of automobiles necessitated the coordination of almost an entire industry, and even though the Crvena Zastava factory was the oldest industrial enterprise in Serbia, founded in 1853, until the mid-1950s it had produced only weapons. From that perspective, Fiat represented both a school and a model for the Yugoslav industrial development. Not surprisingly, the Crvena Zastava factory became one of the biggest industrial companies in Yugoslavia which by the late 1980s had employed almost 56,000 workers. In addition, more than 200 sub-contractor companies from the whole country worked for the Crvena Zastava, making this factory truly the “engine” of the Yugoslav economy. And like the Fiat in Italy, the Crvena Zastava enjoyed a special treatment – it received favourable state loans, credit lines and guarantees, and even writing-off debts in the periods of economic crisis.

How did Tito and the leadership of the League of the Communists of Yugoslavia looked at one of the most important families of Italian capitalism, such as the Agnelli family?

When in the early 1950s American diplomats asked Tito why he continued with the Soviet industrial model of developing only heavy industry, he replied that it was a necessary political strategy designed to prevent Stalin’s supporters in Yugoslavia from accusing him of the betrayal of the socialist ideas. Tito and his closest associates were extremely clever and pragmatic, and tried above all to secure the widest possible autonomy, not only for them but for the whole country.

Cooperation with the holders of big capital, like the Agnelli family, was difficult to justify ideologically, yet considering the political, economic and propaganda impact it was very useful and important.

Therefore, in Kragujevac in 1962, Fiat co-financed the construction of one of the most advanced automobile factories in Europe, designed to model the Italian Mirafiori factory, which produced “fića”, as the first people’s car in the socialist countries.

All of this demonstrated that Yugoslavia was open to economic, political and cultural cooperation with the West, and in that process Italy played the role of a “bridge” for such cooperation. In this way, Tito and Yugoslavia were gradually building a desirable international image. Thus, playing the double game, in 1969 Tito even refused to receive Agnelli during his official business visit to Yugoslavia, and commented: “Why do I have to receive everybody who is coming to the country?”

However, a few days later Tito changed his mind and received Agnelli, but informed his staff that in the future only he could decide who and when he would receive. Tito, however, never hesitated whether to welcome the Italian actresses Sofia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida when they were willing to visit him…

Beside technical-industrial questions, was the Italian influence important in any other aspect? The Crvena Zastava factory, for instance, even had an interesting marketing strategy…

The Fiat truly was the role model for the Crvena Zastava, from unqualified workers on the production lines, up to the senior managers and engineers, and therefore it is difficult to speak about the independent development, even considering the marketing. Of course, this does not mean that there were no original Yugoslav ideas.

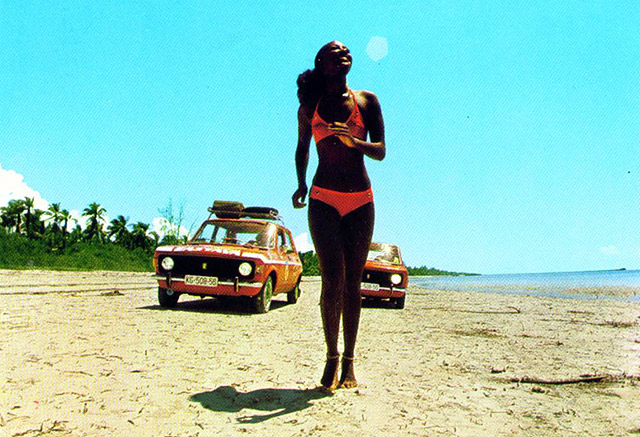

A unique marketing campaign of the Crvena Zastava was the expedition of five Zastava 101 automobiles (based on the Fiat 128 model) which in 1975 travelled from Kragujevac to mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, followed by a large group of cameramen, journalists and photographers.

Other advertising attempts were less successful, one of which was a photo showing a girl in a mini-skirt sitting on the bonnet of the car, in rainy weather. A smiling girl may have been a good idea, but a soaking wet girl, with grey clouds in the background, could arguably sell cars. The photographer, as in a typically planned economy, might have been unable to meet the deadline and was forced to organize the photo-session in spite of the poor weather.

The biggest success of the Crvena Zastava was the export of the original Yugoslav model Yugo to the USA in the second half of the 1980s, even though the Fiat experts warned their Yugoslav colleagues not to pursue this project. Thanks to the aggressive promotional campaign designed by the American experts, for a short period of time Yugo held the title of the best selling European car in the American history. The initial success meant that the warnings coming from the Fiat fell on the deaf ears of the Crvena Zastava managers. This ended in catastrophic results for the Yugoslav automobile industry which could not compete on the demanding American market neither technically nor financially. Today, Yugo is considered to be the worst automobile ever produced anywhere, and it was ridiculed in many Hollywood movies, such as in the third sequel of the Die Hard serial.

To which extent the industrial and economic relationship led to a better understanding between citizens and societies of Italy and Yugoslavia?

The Crvena Zastava workers were learning Italian on the factory language courses since 1962, because it was a necessary precondition for their on-work training in Fiat. This appears to have been particularly important because in the previous period some funny scenes occured. It happened more than once that the Crvena Zastava had received promotional and educational films, which were eventually sent back to the Fiat since among the employees in the Yugoslav factory nobody could translate them. Similarly, only the members of the Yugoslav League of Communists were chosen for the training programs in Italy, and they, in most of the cases, could not understand a word in Italian. During the training in the Fiat facilities they managed to learn only the most basic operations but, on the other hand, they would return to Yugoslavia with a brand new colour TV set and other appliances, a new wardrobe and several pairs of shoes.

Obviously, none of this helped the Crvena Zastava to modernize its production, but it most certainly had a huge impact on the Yugoslav society considering the development of the modern consumer society and the modernization in general.

What happened after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and how did we come to the contemporary relations?

The collapse of the production in the Crvena Zastava started during the 1980s, after Tito’s death. Severing business ties with Italy and other Western partners during the early 1990s, the loss of the Yugoslav market and of sub-contractors in other Yugoslav republics, the imposing of the UN sanctions in 1992 and, finally, the bombardment of the factory in 1999 eventually completely ruined the Zastava. Although Zastava somehow managed to produce up to a couple of thousand automobiles per year during the last two decades, it was only a futile attempt of the government to avoid mass layoffs.

Another difficult problem was the previous debts of the Crvena Zastava towards the Fiat. After the political changes in 2000, and the subsequent lifting of the economic sanctions, these debts had to be settled. In 2005 the Fiat wrote off the majority of the Crvena Zastava’s debts, and at the same time, as a part of the aid package, it licensed the Zastava for the production of the Fiat Punto (Zastava 10). Unfortunately, this was not enough for the salvation of the factory, and on September 29, 2008, the Serbian Government and the Fiat signed a contract for selling this company to the Italian manufacturer. An estimated value of the contract was 950 million Euros, out of which 700 million were to be the Fiat’s investments, while the Serbian Government remained the owner of the 33% of the new factory named Fiat Automobiles Serbia – FAS.

How would you describe Fiat’s position in Serbia today? How important is this Italian company to the Serbian economy? What is the position of the workers in the FAS?

The Fiat Automobiles Serbia factory is one of the biggest industrial facilities in Serbia today and, although this may sound unbelievable, automobiles are the most important Serbian export commodity. Fiat 500L – proudly made in Serbia – is successfully exported to the American market, even though it still did not achieve the export numbers of Yugo in the 1980s, whatever the outcome of that was. The existence of a modern automobile factory is very important for the economic recovery of Serbia, a country that has been de-industrialized in the last two decades.

On the other hand, this situation allows the Fiat to act as a monopolist in Serbia. Today, the public still does not know all the details of the deal between this company and the Serbian Government, as some parts of it are still considered to be a trade secret. And even though Serbian politicians are praising the Fiat’s export results, they avoid admitting that the Fiat is one of the biggest importers as well – the most complex automobile components, like the engine and the gearbox, are imported from Italy and other countries.

At the same time, there is a real and potential danger that the Fiat might change its development policy, downsize or even close down the factory in Kragujevac, which could have a devastating blow for the Serbian economy. Workers are protesting for being badly paid compared to their European counterparts. They work for the average Serbian salary, around 350 Euros per month. As a result of such dissatisfaction, some workers scratched the paint of cars just finished on the assembly line, with screwdrivers. This was of course hushed up.

These are problems and dilemmas of every transitional society. The responsibility is mostly in the leading politicians who, as it seems, still do not have a completely clear strategy for the country’s economic reconstruction. Nevertheless, the fact that the Fiat is doing business in Serbia is a good basis for the future economic development of the country. Provided this cooperation is carefully controlled and directed by the Serbian Government.

To Top

To Top