Ukraine: Slovo, from “house of the word” to nightmare

"Slovo" is an apartment complex for Ukrainian writers, built in the 1920s in the former capital of Ukraine Kharkiv. Securing them a decent home was only a marginal concern: it soon turned into a nightmare of control, delations, and arrests

Ucraina-Slovo-da-casa-della-parola-a-incubo

Image from proslovo.com

(Published in collaboration with Eastjournal )

At the end of the 1920s in the centre of Kharkiv, a city in eastern Ukraine, a single large apartment block was built in the shape of the letter "С" – the "S" of the Cyrillic alphabet. Its shape draws the initial letter of the word слово (slovo), or "word": the building was, indeed, specially designed to house the most important Ukrainian writers, who would be living next to each other in the 66 luxury apartments. In fact, this Soviet architectural-anthropological project also had its dark side: total control of the state over the intelligencija of the newly-born Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkrSSR).

Kharkiv, first capital

A respectable Ukrainian town since the 1820s, the city of Kharkiv – which today has almost a million and a half inhabitants – was an important cultural centre, first under the Russian Empire and then in the early Soviet period. Here, in 1812, the first Ukrainian-printed newspaper of the empire was born, called Char’kovskij Eženedjel’nyk‘ – "The Kharkiv weekly" – which published the first Ukrainian books and editions and which intellectually developed this city in eastern Ukraine, and with it the rest of the country.

From 19 December 1919 to 24 June 1934, Kharkiv was the first capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Although Kiev was the country’s cultural and political centre and capital of the Ukrainian_People’s_Republic, the Bolsheviks who came to power following the 1917 revolutionary uprisings designated Kharkiv as the capital city of the UkrSSR not only for its position (closer to the Russian border), but also for the support they had found in this part of the country. Kharkiv thus became the third most important industrial hub of the entire Soviet Union, as well as a large scientific and cultural centre: it boasted numerous research institutes and among the best universities in the world. Even today, in terms of education and science, Kharkiv’s universities and research institutes are among the best in the country (and sometimes in Eastern Europe), often competing with Kiev’s. The most famous poets, writers, scientists, and artists of Ukrainian and Soviet history were born in Kharkiv: pedagogist and educator Anton Makarenko, scientist Vasil’ Karazin (founder of the homonymous university), and man of letters Volodymyr Dobrovolskij just to name a few; without forgetting the contemporaries Serhij Žadan , author and frontman of two music bands, and Serhij Babkin and Andrij Zaporožcija, both members of the band “5’nizza ”.

The fact that Kharkiv was the capital, therefore, significantly influenced the process of Ukrainisation of the city and the country: in the 1920s the Ukrainian language and culture was able to develop, and the numerous organisations that held literary meetings and discussions declined as early as the 1930s, when Kiev became capital and Kharkiv lost part of its appeal. The capital was moved in 1934, or immediately after the tragedy of the Holodomor (1932-33) which resulted in the death of four million Ukrainians, primarily farmers, from starvation and malnutrition; also for this reason Kharkiv is sometimes remembered as "the capital of the famine". During its three years as the capital, the city gave its best from a cultural point of view and in this atmosphere of rebirth the Slovo housing complex was born.

From dream to nightmare

In the Soviet Union, cultural, ethnic, and religious identity had to be secondary to class, at least in principle. Profession became a defining trait, which grouped people according to duties, habits, needs, and even housing. It was therefore common to come across apartment blocks intended for railway workers, teachers, factory workers, or the party’s nomenclature. For the intellectual class of Kharkiv Slovo was born, a constructivist residential complex literally shaped like a Word.

In those years, construction also responded to actual needs: the poor social and economic living conditions of the first post-war period were felt also among Ukrainian artists. Those who belonged to the old aristocracy and had not emigrated found themselves forced, according to the party’s new rules, to host families of "proletarian comrades" in the "spare" rooms of their former owned apartments (nationalised by the Bolsheviks). "Heart of a dog", by Kiev-born Michail Bulgakov, portrays those years well. Other, less fortunate writers who could not afford to pay for housing (prices in Kharkiv were higher than in Kiev) did as they could, often living in the office or in improvised places, keeping their precious manuscripts in pots to preserve them from mice. So, in the mid-1920s, the peasant writers of the Pluh circle ("Plow"), headed by Ostap Vyšnija , asked the Soviet government for a housing complex that could decently accommodate all the most important Ukrainian intellectuals.

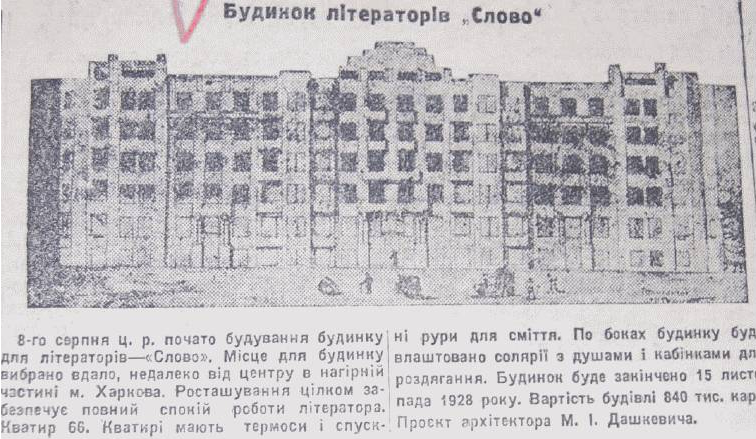

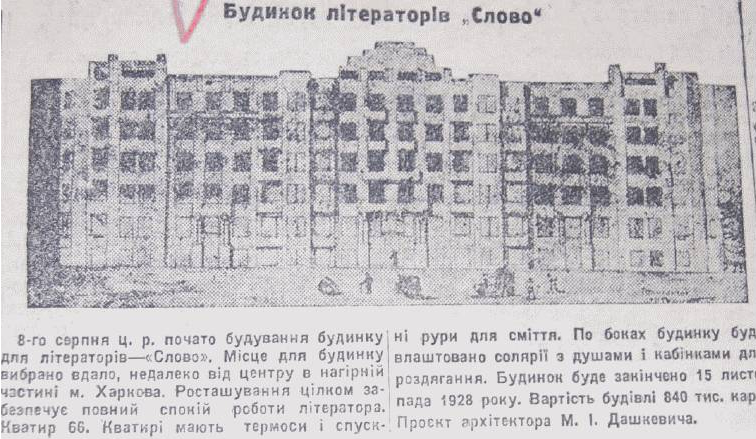

The idea was immediately approved by the Bolsheviks, and the design of the Slovo complex was entrusted to architect Mychaijlo Daškevyč. Although very close to the city centre, Slovo was – and still is – in the middle of the city’s welcoming outskirts, at the current No. 9 of Vulycja Kultury (Culture Street). Entirely built with the best materials available at the time, the 66 apartments – including two for administration – were distributed over 5 floors and accessible through 5 entrances; they all had 3 or 4 rooms and large windows, which was a real luxury for the standard of living of those years; in addition, a nursery school had been set up on the ground floor, while the architect had built a solarium on the roof. Works began in 1927 and lasted for two years. However, some additional funding needed to complete the project came directly from the Kremlin: in 1929 some writers went to Moscow on the occasion of the "Ukrainian Culture Week" and Ostap Vyshnija had the courage to ask Stalin himself for help. Stalin granted his wish the same day.

Why would Stalin care so much about the fate of the Ukrainian intelligentsia? The answer is easy: absolute control of the intellectual class, grouped in a single building, would have been easier than ever. In fact, in 1929, when the first would-be residents were assigned their respective apartments, few could imagine that the telephones specially installed in each flat (apparently uncommon for that time) would be used to spy on most of the inhabitants and even "invite" the most frightened to report their neighbours. It was soon clear, therefore, that a building like Slovo was perfect for the regime, which could easily observe, pressure, persecute, and eliminate every single writer.

In Moscow there is a building that undoubtedly recalls Slovo (and vice versa), both architecturally and functionally: the house on the riverside (Dom na naberežnoj ). Built between 1927 and 1931 in a constructivist style, it housed 505 apartments inhabited by members of the party’s nomenklatura; it is sadly known for the large number of arrests that occurred during the period of the great purges and protagonist of the novel of the same name by Jurij Trifonov.

The short life of the inhabitants of Slovo

Many Ukrainian artists moved to Kharkiv from all over Ukraine and asked for accommodation in Slovo; some had a rather ambiguous past and ideologies, so that the complex gathered writers, poets, directors, and actors more or less sympathetic to the new communist regime. In particular, among the first tenants there were three writers belonging to the Ukrainian Association of Proletarian Writers (Vseukrajnska spilka proletarskyсh pysmennyсhiv or VUSPP ), that fought against bourgeois nationalism and sought to create a "socialist realism" within the world of writers. They were the first to denounce their neighbours more or less voluntarily, starting a period of repression that caused the definitive decline of Slovo and Kharkiv.

Among the first official arrests, in 1931, there was that of actress and writer Galyna Orlivna, wife of poet Klym Polišuk. Jailed on January 20 for not denouncing her "anti-socialist" husband – who was executed with gunfire in 1937, in Karelia, along with 9 other writers – she was sentenced to five years in prison and was never able to return in Ukraine. The other arrests followed suit, all on similar charges: "counter-revolutionary incitement through literary works". 1933 was the most tragic year: Ukrainian writer Mychajilo Jalovyj was arrested for "espionage", initially sentenced to ten years of forced labour, then to the death penalty; the following day, during a conversation on the Jalovyj case between neighbours, writer Mykola Chvyl’ovyj shot himself in his room, full of despair.

The wave of repressions hit 40 of the 66 apartments: 33 inhabitants were executed, 5 sentenced to death, a suicide, and one death in unclear circumstances. The repression coincided with one of the most controversial famines ever, that of Holodomor, regarded as an intentional genocidal policy towards the Ukrainian population.

Slovo’s fate

In 1934, when the capital was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev, many writers had the opportunity to leave the city and Slovo. The complex was left uninhabited for several years, particularly during the Second World War, and it was repopulated by writers and painters of the new generation only from the 1950s. Today it is inhabited by ordinary citizens, not necessarily by writers or their family members.

In order not to forget this period of repression, in March 2017 the ProSlovo research project was launched, entirely dedicated to this constructivist building and the stories of its residents. A documentary was also produced that follows the life and events of the "house of the word", from its birth to its decline and abandonment. Slovo was, and still remains, a little chapter in the history of Ukraine.

The ProSlovo documentary:

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Ukraine: Slovo, from “house of the word” to nightmare

"Slovo" is an apartment complex for Ukrainian writers, built in the 1920s in the former capital of Ukraine Kharkiv. Securing them a decent home was only a marginal concern: it soon turned into a nightmare of control, delations, and arrests

Ucraina-Slovo-da-casa-della-parola-a-incubo

Image from proslovo.com

(Published in collaboration with Eastjournal )

At the end of the 1920s in the centre of Kharkiv, a city in eastern Ukraine, a single large apartment block was built in the shape of the letter "С" – the "S" of the Cyrillic alphabet. Its shape draws the initial letter of the word слово (slovo), or "word": the building was, indeed, specially designed to house the most important Ukrainian writers, who would be living next to each other in the 66 luxury apartments. In fact, this Soviet architectural-anthropological project also had its dark side: total control of the state over the intelligencija of the newly-born Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkrSSR).

Kharkiv, first capital

A respectable Ukrainian town since the 1820s, the city of Kharkiv – which today has almost a million and a half inhabitants – was an important cultural centre, first under the Russian Empire and then in the early Soviet period. Here, in 1812, the first Ukrainian-printed newspaper of the empire was born, called Char’kovskij Eženedjel’nyk‘ – "The Kharkiv weekly" – which published the first Ukrainian books and editions and which intellectually developed this city in eastern Ukraine, and with it the rest of the country.

From 19 December 1919 to 24 June 1934, Kharkiv was the first capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Although Kiev was the country’s cultural and political centre and capital of the Ukrainian_People’s_Republic, the Bolsheviks who came to power following the 1917 revolutionary uprisings designated Kharkiv as the capital city of the UkrSSR not only for its position (closer to the Russian border), but also for the support they had found in this part of the country. Kharkiv thus became the third most important industrial hub of the entire Soviet Union, as well as a large scientific and cultural centre: it boasted numerous research institutes and among the best universities in the world. Even today, in terms of education and science, Kharkiv’s universities and research institutes are among the best in the country (and sometimes in Eastern Europe), often competing with Kiev’s. The most famous poets, writers, scientists, and artists of Ukrainian and Soviet history were born in Kharkiv: pedagogist and educator Anton Makarenko, scientist Vasil’ Karazin (founder of the homonymous university), and man of letters Volodymyr Dobrovolskij just to name a few; without forgetting the contemporaries Serhij Žadan , author and frontman of two music bands, and Serhij Babkin and Andrij Zaporožcija, both members of the band “5’nizza ”.

The fact that Kharkiv was the capital, therefore, significantly influenced the process of Ukrainisation of the city and the country: in the 1920s the Ukrainian language and culture was able to develop, and the numerous organisations that held literary meetings and discussions declined as early as the 1930s, when Kiev became capital and Kharkiv lost part of its appeal. The capital was moved in 1934, or immediately after the tragedy of the Holodomor (1932-33) which resulted in the death of four million Ukrainians, primarily farmers, from starvation and malnutrition; also for this reason Kharkiv is sometimes remembered as "the capital of the famine". During its three years as the capital, the city gave its best from a cultural point of view and in this atmosphere of rebirth the Slovo housing complex was born.

From dream to nightmare

In the Soviet Union, cultural, ethnic, and religious identity had to be secondary to class, at least in principle. Profession became a defining trait, which grouped people according to duties, habits, needs, and even housing. It was therefore common to come across apartment blocks intended for railway workers, teachers, factory workers, or the party’s nomenclature. For the intellectual class of Kharkiv Slovo was born, a constructivist residential complex literally shaped like a Word.

In those years, construction also responded to actual needs: the poor social and economic living conditions of the first post-war period were felt also among Ukrainian artists. Those who belonged to the old aristocracy and had not emigrated found themselves forced, according to the party’s new rules, to host families of "proletarian comrades" in the "spare" rooms of their former owned apartments (nationalised by the Bolsheviks). "Heart of a dog", by Kiev-born Michail Bulgakov, portrays those years well. Other, less fortunate writers who could not afford to pay for housing (prices in Kharkiv were higher than in Kiev) did as they could, often living in the office or in improvised places, keeping their precious manuscripts in pots to preserve them from mice. So, in the mid-1920s, the peasant writers of the Pluh circle ("Plow"), headed by Ostap Vyšnija , asked the Soviet government for a housing complex that could decently accommodate all the most important Ukrainian intellectuals.

The idea was immediately approved by the Bolsheviks, and the design of the Slovo complex was entrusted to architect Mychaijlo Daškevyč. Although very close to the city centre, Slovo was – and still is – in the middle of the city’s welcoming outskirts, at the current No. 9 of Vulycja Kultury (Culture Street). Entirely built with the best materials available at the time, the 66 apartments – including two for administration – were distributed over 5 floors and accessible through 5 entrances; they all had 3 or 4 rooms and large windows, which was a real luxury for the standard of living of those years; in addition, a nursery school had been set up on the ground floor, while the architect had built a solarium on the roof. Works began in 1927 and lasted for two years. However, some additional funding needed to complete the project came directly from the Kremlin: in 1929 some writers went to Moscow on the occasion of the "Ukrainian Culture Week" and Ostap Vyshnija had the courage to ask Stalin himself for help. Stalin granted his wish the same day.

Why would Stalin care so much about the fate of the Ukrainian intelligentsia? The answer is easy: absolute control of the intellectual class, grouped in a single building, would have been easier than ever. In fact, in 1929, when the first would-be residents were assigned their respective apartments, few could imagine that the telephones specially installed in each flat (apparently uncommon for that time) would be used to spy on most of the inhabitants and even "invite" the most frightened to report their neighbours. It was soon clear, therefore, that a building like Slovo was perfect for the regime, which could easily observe, pressure, persecute, and eliminate every single writer.

In Moscow there is a building that undoubtedly recalls Slovo (and vice versa), both architecturally and functionally: the house on the riverside (Dom na naberežnoj ). Built between 1927 and 1931 in a constructivist style, it housed 505 apartments inhabited by members of the party’s nomenklatura; it is sadly known for the large number of arrests that occurred during the period of the great purges and protagonist of the novel of the same name by Jurij Trifonov.

The short life of the inhabitants of Slovo

Many Ukrainian artists moved to Kharkiv from all over Ukraine and asked for accommodation in Slovo; some had a rather ambiguous past and ideologies, so that the complex gathered writers, poets, directors, and actors more or less sympathetic to the new communist regime. In particular, among the first tenants there were three writers belonging to the Ukrainian Association of Proletarian Writers (Vseukrajnska spilka proletarskyсh pysmennyсhiv or VUSPP ), that fought against bourgeois nationalism and sought to create a "socialist realism" within the world of writers. They were the first to denounce their neighbours more or less voluntarily, starting a period of repression that caused the definitive decline of Slovo and Kharkiv.

Among the first official arrests, in 1931, there was that of actress and writer Galyna Orlivna, wife of poet Klym Polišuk. Jailed on January 20 for not denouncing her "anti-socialist" husband – who was executed with gunfire in 1937, in Karelia, along with 9 other writers – she was sentenced to five years in prison and was never able to return in Ukraine. The other arrests followed suit, all on similar charges: "counter-revolutionary incitement through literary works". 1933 was the most tragic year: Ukrainian writer Mychajilo Jalovyj was arrested for "espionage", initially sentenced to ten years of forced labour, then to the death penalty; the following day, during a conversation on the Jalovyj case between neighbours, writer Mykola Chvyl’ovyj shot himself in his room, full of despair.

The wave of repressions hit 40 of the 66 apartments: 33 inhabitants were executed, 5 sentenced to death, a suicide, and one death in unclear circumstances. The repression coincided with one of the most controversial famines ever, that of Holodomor, regarded as an intentional genocidal policy towards the Ukrainian population.

Slovo’s fate

In 1934, when the capital was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev, many writers had the opportunity to leave the city and Slovo. The complex was left uninhabited for several years, particularly during the Second World War, and it was repopulated by writers and painters of the new generation only from the 1950s. Today it is inhabited by ordinary citizens, not necessarily by writers or their family members.

In order not to forget this period of repression, in March 2017 the ProSlovo research project was launched, entirely dedicated to this constructivist building and the stories of its residents. A documentary was also produced that follows the life and events of the "house of the word", from its birth to its decline and abandonment. Slovo was, and still remains, a little chapter in the history of Ukraine.

The ProSlovo documentary: