Disinformation, technology giants, and our critical skills

Online disinformation is a complex phenomenon that can become extremely harmful to society. As we are faced with the power of technology giants, short-term policies, and implications for freedom of expression, it is crucial to promote critical thinking, media literacy, and reflection on these issues in all age groups

La-disinformazione-i-giganti-e-le-nostre-abilita-critiche

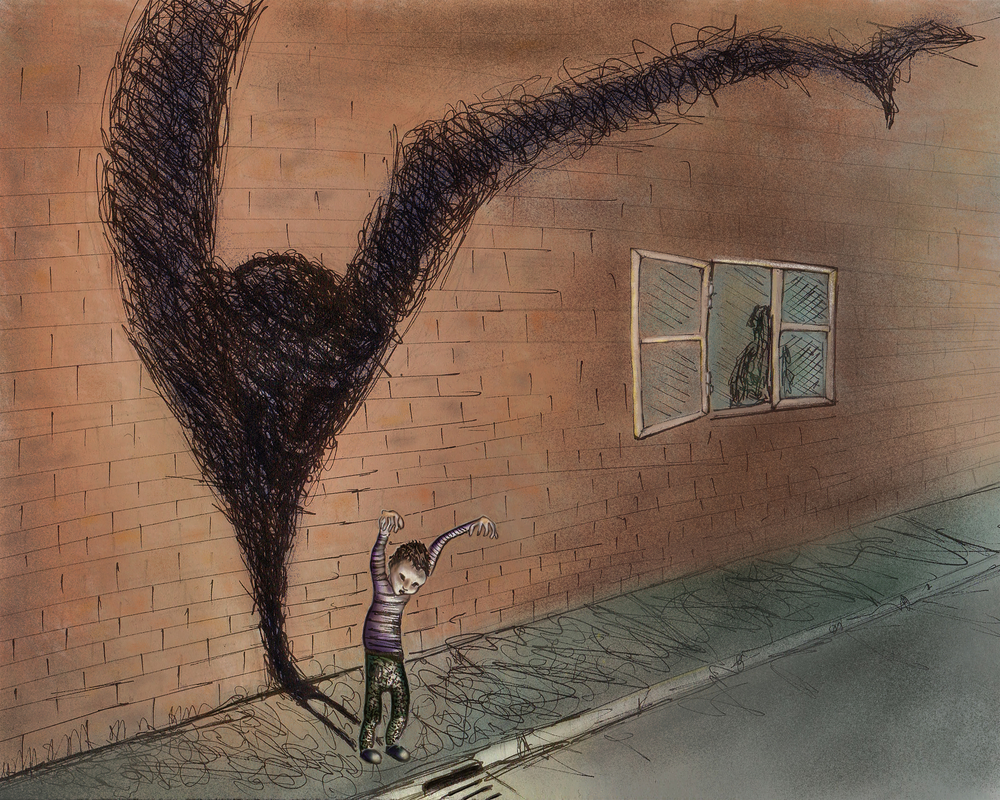

© Juhasz Sz/Shutterstock

Online disinformation has become a stable component of the digital habitat – so much so that, at the global level, sites specialising in “fact-checking” keep multiplying, aiming to verify and expose online fake news. Thanks to the Internet and social media, everyone can create and distribute content in real time – this means that anyone can also be exposed to online disinformation, as anyone can create and disseminate it, as often happens due to lack of attention or expertise in assessing content in different media contexts.

The increasingly vast literature on disinformation describes the phenomenon by referring to all sorts of problematic, false, misleading, or partial content published on websites and disseminated through social media for profit or in order to influence society. Several scholars have tried to define the phenomenon of "fake news", focusing on the reason and motive as well as mode of dissemination.

Disinformation. False and harmful

What seems clear is that we are faced with a complex phenomenon that presents numerous stratifications. One of the most exhaustive terms used to define this complexity is “information disorder” . The term, conceived by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, includes – but not exlusively – disinformation, which is placed at the intersection of false information (misinformation) and intentionally damaging information (malinformation).

As the two scholars explain, this space can be animated by official actors (such as intelligence services, political parties, media, public relations agencies, or lobbies) or unofficial ones (groups of citizens) – with political, economic, but also psychological or social motivations (for example, the desire to be connected with a certain group online or offline) – which use a variety of formats (texts, images, audio, and video materials) in constant evolution.

The choice of technology giants

However, it is clear that the role of online platforms is of central importance within this framework. Ultimately, technology giants (Google, Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp, Snapchat etc.) are those that decide what we see online. In recent years, there has increasingly been talk of how the domination of these companies over information has quickly overshadowed the role of traditional publishing.

The algorithms of technology giants are programmed to maximise our attention and the time we spend online, in order to maximise profits too. Companies exploit our cognitive biases and the traces we leave in the digital space to develop algorithms that offer us information modelled on our behaviour.

Drawing on these premises, several studies have looked at “echo chambers ” and “filter bubbles ”, stressing that the companies’ algorithmic mechanism risks creating "bubbles" where people with similar behaviours are brought together, thus fostering greater polarisation of society.

Disinformation in political processes

A similar argument is made for the influence that these mechanisms can exert on our political positions, as highlighted for example with regard to the 2016 elections in the United States or Brexit. In both cases, the debate on the exploitation of the net and social media by external forces to determine electoral result is still ongoing. The two examples are not isolated cases, given that the fear of external and in particular Russian interference is also at the origin of the European Union’s initiatives to counter “fake news”.

In this context, lack of transparency in the process of collecting and using our data by technology giants is one of the most important issues to be addressed. Recently, and only thanks to the insistence of institutions and public opinion, platforms have been pushed to adopt some preemptive measures against disinformation, like the self-regulatory code of practice presented to the European Union (EU). However, even with the most recent tools put in place, especially with regard to online electoral propaganda, the solutions proposed by the platforms still seem far from providing a clear, transparent framework.

Solutions for a complex problem

The unlimited dissemination potential of online disinformation has led international organisations such as the UN and the OSCE to discuss several strategies to counteract the phenomenon , not least the need to support quality journalism, as its marked erosion is an integral part of the "fake news" problem.

While discussing whether the state should manage the phenomenon or leave it to private companies, numerous solutions are put forward, each with its strengths and weaknesses. Experts are increasingly stressing the need to adopt several complementary tools at the same time, and technological solutions are being put forward to address the issue – new algorithms, indexing, use of metadata, etc. – with several new startups offering innovative tools, while some countries, such as Germany and France, are also adopting regulatory approaches.

A long-term response: media and information literacy

Among the long-term solutions, it is of primary importance to focus on media and information literacy (MIL) as the ability to access, analyse, assess, and create content in different media contexts. First, countries with high levels of education, media literacy, and freedom of the press are those where we find greater capacity for resilience to disinformation. Then, in the face of the power of technology giants, regulatory approaches, short-term policies, and implications for freedom of expression, it is only by enhancing people’s comprehension and interpretation skills that society can try to cope with a constantly evolving digital context.

Against this backdrop, it is certainly important to promote critical thinking and media literacy in schools and traditional educational venues, but it is also fundamental to find ways to promote reflections on these issues in all age groups, even among those that have grown up in years in which sources of information were much fewer. Therefore, inclusive approaches to media literacy are needed that can involve the entire population exposed to new media. Efforts to raise awareness about the media context are the safest long-term investment to allow a public conversation that is less poisoned or distracted by disinformation mechanisms, without resorting to opaque tools such as algorithmic forms of censorship of disinformation or legislative approaches that risk limiting fundamental democratic freedoms.

To learn more

Disinformation is among the most pressing issues of our time. OBCT has devoted an in-depth dossier to this issue, starting from the materials of the Resource Center on Press and Media Freedom in Europe. Go to the Special Dossier on Disinformation

This publication has been produced within the project ESVEI, supported in part by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the OSIFE of the Open Society Foundations. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa.

Tag: ESVEI

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Disinformation, technology giants, and our critical skills

Online disinformation is a complex phenomenon that can become extremely harmful to society. As we are faced with the power of technology giants, short-term policies, and implications for freedom of expression, it is crucial to promote critical thinking, media literacy, and reflection on these issues in all age groups

La-disinformazione-i-giganti-e-le-nostre-abilita-critiche

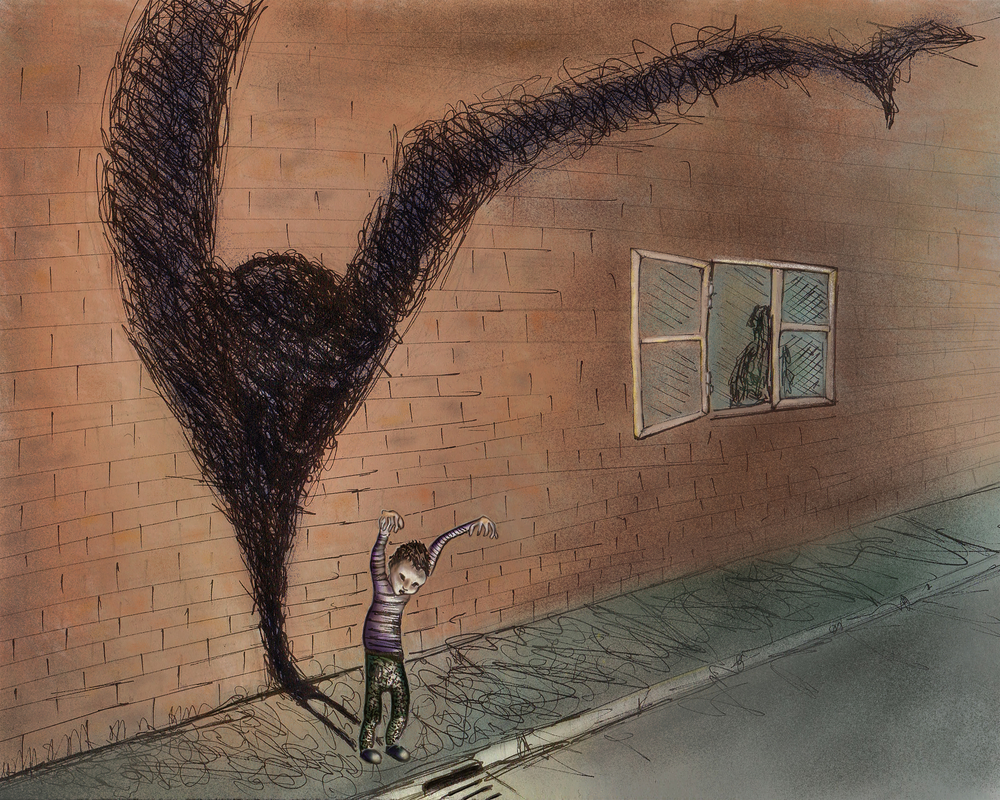

© Juhasz Sz/Shutterstock

Online disinformation has become a stable component of the digital habitat – so much so that, at the global level, sites specialising in “fact-checking” keep multiplying, aiming to verify and expose online fake news. Thanks to the Internet and social media, everyone can create and distribute content in real time – this means that anyone can also be exposed to online disinformation, as anyone can create and disseminate it, as often happens due to lack of attention or expertise in assessing content in different media contexts.

The increasingly vast literature on disinformation describes the phenomenon by referring to all sorts of problematic, false, misleading, or partial content published on websites and disseminated through social media for profit or in order to influence society. Several scholars have tried to define the phenomenon of "fake news", focusing on the reason and motive as well as mode of dissemination.

Disinformation. False and harmful

What seems clear is that we are faced with a complex phenomenon that presents numerous stratifications. One of the most exhaustive terms used to define this complexity is “information disorder” . The term, conceived by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan, includes – but not exlusively – disinformation, which is placed at the intersection of false information (misinformation) and intentionally damaging information (malinformation).

As the two scholars explain, this space can be animated by official actors (such as intelligence services, political parties, media, public relations agencies, or lobbies) or unofficial ones (groups of citizens) – with political, economic, but also psychological or social motivations (for example, the desire to be connected with a certain group online or offline) – which use a variety of formats (texts, images, audio, and video materials) in constant evolution.

The choice of technology giants

However, it is clear that the role of online platforms is of central importance within this framework. Ultimately, technology giants (Google, Facebook, Twitter, Whatsapp, Snapchat etc.) are those that decide what we see online. In recent years, there has increasingly been talk of how the domination of these companies over information has quickly overshadowed the role of traditional publishing.

The algorithms of technology giants are programmed to maximise our attention and the time we spend online, in order to maximise profits too. Companies exploit our cognitive biases and the traces we leave in the digital space to develop algorithms that offer us information modelled on our behaviour.

Drawing on these premises, several studies have looked at “echo chambers ” and “filter bubbles ”, stressing that the companies’ algorithmic mechanism risks creating "bubbles" where people with similar behaviours are brought together, thus fostering greater polarisation of society.

Disinformation in political processes

A similar argument is made for the influence that these mechanisms can exert on our political positions, as highlighted for example with regard to the 2016 elections in the United States or Brexit. In both cases, the debate on the exploitation of the net and social media by external forces to determine electoral result is still ongoing. The two examples are not isolated cases, given that the fear of external and in particular Russian interference is also at the origin of the European Union’s initiatives to counter “fake news”.

In this context, lack of transparency in the process of collecting and using our data by technology giants is one of the most important issues to be addressed. Recently, and only thanks to the insistence of institutions and public opinion, platforms have been pushed to adopt some preemptive measures against disinformation, like the self-regulatory code of practice presented to the European Union (EU). However, even with the most recent tools put in place, especially with regard to online electoral propaganda, the solutions proposed by the platforms still seem far from providing a clear, transparent framework.

Solutions for a complex problem

The unlimited dissemination potential of online disinformation has led international organisations such as the UN and the OSCE to discuss several strategies to counteract the phenomenon , not least the need to support quality journalism, as its marked erosion is an integral part of the "fake news" problem.

While discussing whether the state should manage the phenomenon or leave it to private companies, numerous solutions are put forward, each with its strengths and weaknesses. Experts are increasingly stressing the need to adopt several complementary tools at the same time, and technological solutions are being put forward to address the issue – new algorithms, indexing, use of metadata, etc. – with several new startups offering innovative tools, while some countries, such as Germany and France, are also adopting regulatory approaches.

A long-term response: media and information literacy

Among the long-term solutions, it is of primary importance to focus on media and information literacy (MIL) as the ability to access, analyse, assess, and create content in different media contexts. First, countries with high levels of education, media literacy, and freedom of the press are those where we find greater capacity for resilience to disinformation. Then, in the face of the power of technology giants, regulatory approaches, short-term policies, and implications for freedom of expression, it is only by enhancing people’s comprehension and interpretation skills that society can try to cope with a constantly evolving digital context.

Against this backdrop, it is certainly important to promote critical thinking and media literacy in schools and traditional educational venues, but it is also fundamental to find ways to promote reflections on these issues in all age groups, even among those that have grown up in years in which sources of information were much fewer. Therefore, inclusive approaches to media literacy are needed that can involve the entire population exposed to new media. Efforts to raise awareness about the media context are the safest long-term investment to allow a public conversation that is less poisoned or distracted by disinformation mechanisms, without resorting to opaque tools such as algorithmic forms of censorship of disinformation or legislative approaches that risk limiting fundamental democratic freedoms.

To learn more

Disinformation is among the most pressing issues of our time. OBCT has devoted an in-depth dossier to this issue, starting from the materials of the Resource Center on Press and Media Freedom in Europe. Go to the Special Dossier on Disinformation

This publication has been produced within the project ESVEI, supported in part by a grant from the Foundation Open Society Institute in cooperation with the OSIFE of the Open Society Foundations. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa.

Tag: ESVEI