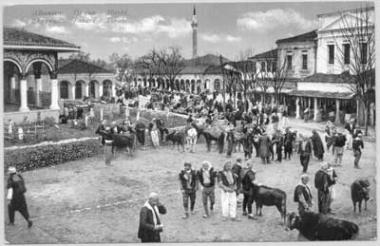

Tirana's old çarshija

An Ottoman-style market, a çarshija, right in the heart of Tirana, of which today only faint memories remain. Architecture, social relations and memory in an interview with the anthropologist Armanda Kodra

Armanda Kodra is an Albanian anthropologist who principally studies comparative cultural anthropology in the Balkans. She has mainly focused on the subject of the çarshijas *, policies on national and religious identities, collective memory and oral history. She is currently working as an anthropologist at the Institute of Cultural Anthropology of Tirana and teaches Balkan Anthropology at the Tirana public university. She collaborates with various academic and cultural journals in Albania and abroad, including Fatos Lubonja’s “Perpjekja”.

In which part of Tirana was the çarshija?

It was more or less in the center of the city where the Palace of Culture now stands, and in the garden behind it. It had been there since the founding of Tirana. It was probably the construction of the çarshija that made Tirana a city. Once upon a time, the Sulejman Pasha Mosque was near there. It was torn down to build public restrooms, intentionally… The Mosque was heavily damaged by the bombings, and the communists left it to there, abandoned.

Today the foundation stone of the Mosque is regarded as the foundation stone of the city. It is said, as a matter of fact, that Tirana was founded in 1614. Evlija Celebija, an Ottoman traveler that must have visited the city around 30 years after its founding, describes the çarshija as a very big space. Even though he was known for his tendency to magnify what he observed, we are led to think that that space had acquired great importance for the city.

Today, though, practically nothing remains of Tirana’s çarshija…

The çarshijas of the large Albanian cities were torn down by Hoxha’s regime. Practically nothing remains of the çarshijas of Berat, Kavaja, and Elbasan, to name a few. It was not always a deliberate destruction, though. It started out by discouraging private property and initiative. Then in the 50s, public craft enterprises were established, and almost each of the main cities had one. Their main objective was that of producing handicrafts mainly considered as souvenirs. This led the çarshijas to lose their importance. The demolition and re-definition of the cities’ architecture came at a later time.

Why were these historical neighborhoods of the city demolished?

It was claimed that socialist cities were no place for such Ottoman buildings. The city was to be freed from signs of the past. In some cases, though, çarshijas lost their importance in a more natural way. Because of this anti-Ottoman orientation, the regime did nothing to preserve them, even though they were places of cultural and historical interest of the city. In Scutari, for example, there was a gradual shifting towards the Northern part of the city center. The çarshija was underneath the fortress, an area which became more and more marginal. It became more and more inconvenient to reach. In that case, it was natural for the çarshija to die, because it was no longer functional.

If we wanted to know what the Tirana çarshija was like, how would you describe it?

Çarshijas are usually not different from each other from the architectural point of view. The shape depends on the relief of the city where they are built. In the early days they were built in wood and thus highly exposed to fires. They were rebuilt but unfortunately always in wood. Only later in time were they built with more stable structures.

Çarshijas are nets of streets and alleys where you can find stores and various craftsmen’s shops. It is an exclusively business district, people do not live there but they only go there to buy, work and socialize. You can find all sorts of craftsmen.

The large enough squares, formed by the joining of various alleys, were the places where peasants sold their own produce. It was usually the female peasants who harvested the produce of all the women in a village and sold them in the çarshija. The important aspect, though, is that the çarshijas were centers where people actually socialized. They were meeting points not only for the citizens but also for the people from minor villages around the city.

People met in the çarshija to close business deals, to make friends and arrange marriages. It was a typical public place. It is right from there that comes the culture of cafés, still very much alive today in the Balkans and in the formerly Ottoman area in general. Cafés are still very important for Balkans as places of leisure, as they often appear to foreigners: they are actually key public places for people’s social life, they are meeting places and places for confrontation. One can easily say that all life flows in the cafés.

Were they self-sufficient places of commerce?

No, they were not. They of course had great relations with port cities, so they were able to keep relations alive, with Venice in particular. In the çarshija there were wholesalers who supplied goods from Venice.

Among the merchants of the çarshija there was someone who had a ship and used it for trans-Adriatic trades. Until the birth of the nation-state, so until the 19th century, the concept of border did not exist in the Balkans. As a consequence there was continuous trade within the region. The çarshija was a meeting point also for the various ethnicities and languages.

It was the multi-ethnic place par excellence. But that did not impede communication and mutual understanding at all: often, the çarshija’s merchants or craftsmen even invented secret languages so outsiders could not understand them. They were a mixture of Balkan languages that followed well defined criteria, such as Albanian lexicon and Serbo-Croatian grammar, combined in such a way that no mother-tongue of any of the languages could understand. It is an extremely interesting phenomenon that overcomes ethnic and linguistic barriers.

How did you collect material on a part of the city that no longer exists?

There is still living memory of this place, even though it is fading from year to year. It is very difficult to collect material, since the only way is by doing interviews, talking to people. Only those who are older than 60 years of age today can vaguely remember. What keeps recurring most in the interviews is minor details of everyday life. Many boast that their families had stores in the çarshija, mainly to let you know that they belong to families native of Tirana and do not come from the suburbs, drawing on stereotypes that make old and new inhabitants of the capital, coming from everywhere especially in the past few years, grow more and more apart.

One difficulty I always encounter, moreover, is the reserved nature of Albanians in general. If you try and ask for details on something, people shut themselves off, they stop talking, they grow distrustful. To me it is the usual Sigurimi syndrome [editor’s note: Sigurimi, secret services at the time of the regime] that still affects Albanians. They think that I am really doing this for some census and that they are then going to be called to account for who knows what political wickedness.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

To Top

To Top