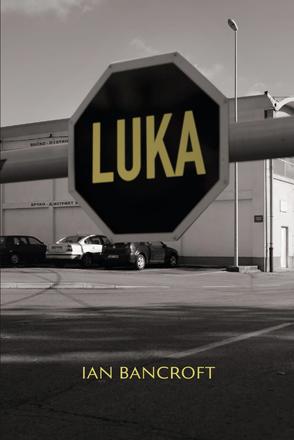

This is the first of two extracts from Ian Bancroft’s new novel, which tells of lives scarred by wars past and present and whose main characters - L., U., K., and A. - are confronted with the dilemmas of truth and justice, and the struggle to reconcile and forgive

Grasping it with her right hand, A. held the Prosecutor’s letter up towards the light. The paper appeared browned, as though sent from another age; by a chronicler from the past dedicated to recounting the details of their present, even if they be confined to the annals of history, where the ink would fade, or moths may devour the edges, to be mishandled or misplaced. Only a keen archivist, straining for a speck of historical gold dust, sporting those white gloves used to handle jewels of immense worth, clutching a magnifying glass through which she strains one eye, will retrieve those very words and give them new significance, new meaning. A prism through which the light of the past shines and is distorted in the present.

It is no coincidence that libraries and museums are among the first objects to perish after the outbreak of war. Significant manuscripts and tombs - painstakingly etched, sketched, or stitched, with coppers and golds, strands of cotton and silk, on parchment or bleached calfskin – instantly and eternally lost to humanity. Not just threads of paper but the very yarns of co-existence in whose grasp all were entwined. Only a few precious books will be saved by singed hands flailing amidst a hail of bullets fired by those unswerving in their determination to destroy. A young librarian will perish, rescuing those volumes untouched by the flames, assassinated by a sniper with the precision of the decimal system over which she presided. As her motionless body falls, she clutches a book to her chest. It matters not what the title is, for in her eyes they are all equally worthy of salvaging. A cellist will lament her death and that of others from amidst the ruins.

Here history caught up with the calligraphers, the illuminators, the archivists, with those who once fled the Inquisition and evaded fascism, who risked their lives to ensure such priceless works survived for at least another generation. For each, the threats were always genuine, always earnest, even in places deemed less prone to catastrophe. Were the tears shed for all those inestimable losses of heritage captured in a large capsule or a thousand silver flagons, then the very fires themselves would have been subdued immediately. Millions of fragments, each as unique as snowflakes, would catch in the wind’s uplifts to irritate the eyes and throats of those exploiting their hillside advantage. And yet still they would shed no tears; still they would feel no remorse.

These were not just bricks and mortar, but places people identified with, in whose light and shadows they were nurtured and inspired. Even when taken for granted - decay spreading from the foundations up through their creaking wooden structures; crumbling gargantuan sculptures; fallen slates and rusted iron supports; broken stained glass mosaics – their imagination restored these very edifices to their former glory. Many historical buildings are ultimately returned to their original state, obliterating the scars of war. These perfect replicas stand majestic and let the perpetrators and their offspring forget the wanton crimes committed in their name. By scrubbing out the stains, these reminders of violence and bloodshed are diluted, even removed, and confined to the memories of those for whom their victimhood is a recurring nightmare.

The Prosecutor’s letter arrived unexpectedly. It had been hand-delivered. A. hurriedly hid it in her handbag with the haste of someone facing potential inquisition. That evening she found sufficient privacy to read. The Prosecutor’s warnings about its contents meant little; her life had already been affected by too many things beyond her control. Only when her father was mentioned did she pause. It was not that she had forgotten him; on the contrary, she was also sure that he was dead. There had been no clues about his last moments or where he might lie - no witnesses, rumours, or gossip. He had vanished into thin air. Though there were ever more testimonies about the past, his name never surfaced. None dared to speculate what might have happened to him.

Were A. to confine the Prosecutor’s letter to history, to tear it up into a thousand pieces scattered in the fireplace, to rise only skywards and into eternity, then there would be nothing else to pursue; neither the cause of justice nor the search for truth about her father’s fate. The assertions of a crime committed would be confined to the realm of gossip and rumour that only tend to subsume one another, to be ridden with lies and distortions, claims and counterclaims, relativisations and outright denials. To continue the struggle demanded energy and perseverance that she wasn’t sure she possessed. Even when nothing else changed, time moved on.

The stories of her great-grandfather nestled in her mind as she lay awake that evening contemplating the letter and its contents, the stories of that one true love whose very image taunted him until his dying day. Pursued throughout life by the possibility, no matter how slim, that she had survived, that the waters had washed her ashore, and memories lost in the maelstrom would gradually resurface. Daily reminders of their love – the riverside air they had inhaled in unison, the parks in which they had fed the ducks, the peaks conquered together – that would reawaken in her a desire to be reunited, or at least to explore a past that had once been her future.

A. harboured no illusions that her father was alive to this day. There were no daydreams or apparent sightings. Yet she required confirmation that he was indeed dead. It was a contradiction that she could not reconcile.

Ian Bancroft is a writer based in the former Yugoslavia.

To Top

To Top