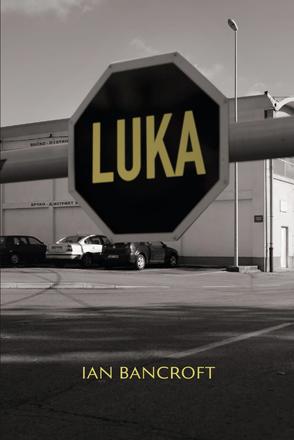

This is the second of two extracts from Ian Bancroft’s new novel, which tells of lives scarred by wars past and present, whose main characters - L., U., K., and A. - are confronted with the dilemmas of truth and justice, and the struggle to reconcile and forgive

The air raid sirens rang out in vain. They were too late. They were always too late. Sometimes they never came or only after a barrage of explosions had already served as ample warning of impending mutilation. When they did sound, it was inevitably to announce death and destruction and to mobilise hands to clear the wreckage. Sometimes people ignored them entirely, weary of seeking shelter simply because of the murderous intent of the invisible adversary wedged up on the hillside; their binoculars or rifle sights focused upon carefully or randomly selected targets, biding their time before deciding upon the fate of a fellow human being.

For those huddled beneath, the waiting was often as torturous as the onslaught, the foe whose eyes they could feel but could not see. Only the glint of the sun would occasionally disclose their position. The snipers were the most insidious, training their sights upon torsos several kilometres away. The scope magnified the intended victim so they felt they could reach out and touch them. Every expression was visible – the fear and loathing, the pain and exhaustion. The panic-stricken faces sprinting from one relief to another, or the innocence of snatched play amidst a gap in the rain clouds. They did not discriminate based on age. Children and elderly people were shot in the forehead if they were lucky, or otherwise in the stomach or thigh to bleed out slowly; those first responders were often too weak to apply sufficient pressure to the wound.

What was once a facade now framed the interior of a house high on the hillside, its contents exposed to the outside world. A pair of trousers was neatly hung up in a wardrobe, with a shirt draped over a wooden chair, awaiting the body for which they were tailored. On the back of the bedroom door, the arms of a jacket remained slumped in resignation. Occasional strips of wallpaper decorated the wall that separated two exposed, weathered rooms, littered with shards of glass and dirt, now indistinguishable from one another. Once cluttered with artefacts, they are now desolate; their walls riddled with pockmarks from which one could decipher birds of prey, hunted animals, or another mammal of foreboding. An empty picture frame was askew, its contents - a coastal scene, family portrait, or whatever - long since faded, memories of which might or might not endure.

Downstairs, the dining table was still laid for breakfast; a boiled egg sat upright in its holder with a crack in its crown alongside an empty mug, plate, and knife. Ashes in the fireplace were the last undisturbed remnant of a family huddled, a contented couple, or an indifferent child. The abandoned props of a life humbly lived and hurriedly left behind, of habits shared across households, borders, and generations. The perpetrators, the warmongers, went to considerable lengths in their desire to cleanse the land, to eradicate the foundations of co-existence, to erase all traces of similarities now made different, and to proclaim alien presences on their pure, unsullied soil.

A mortar shell hissed and whistled as it passed over Old Town’s periphery, its trajectory meticulously calculated and refined through experience, callously drawing upon the near misses to perfect its aim. Whether firing at random or at will, there was no collateral damage. Nor could they ever run out of targets, even when the last person had fallen or fled, for the bombardment was to make clear that their continued existence would not be tolerated. The shelling would continue, even if not a single soul remained, to deter those who would ponder returning; to make clear that this was now forbidden land.

As soon as the mortar was launched, the New Towners, firing from their familiar vantage point, knew exactly where it would hit; and which lives would be wrecked, what devastation would be wrought. Their bid for liberty from Old Town would not be stopped. They had come too far to entertain the possibility of compromise. This first war, the Patriotic War, presented a historic opportunity they felt they could not afford to waste.

Craning their necks, they admired the arch of its flight, likening it to a bird of prey; an eagle swooping to pluck trout from fast-flowing waters, or snatching a field mouse in its sharp claws from its sanctuary in the long grass. To the naked eye, it appeared to wobble and rotate out of control, slowing to the point of stalling before recovering. Serenely it glided, the tail fin stabilising the mortar’s body. They marvelled at its flight, mouths gasping in nervous anticipation. There were no tinges of regret, shame, or remorse for targeting innocents. These men, for they were nearly always men, were blind to the distinction between combatants and civilians, between the armed and the defenceless, between those who cheered for war and those consumed by it.

A child looked skywards, awed by this apparent shooting star, as her mother screamed at her to get inside, finally plucking up the courage to tell her that three of her schoolmates were dead, massacred that morning by the very same device. They shouldn’t have been playing outside, but lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same place, at least not on the same day, or so the mother had convinced herself. A few days later, she would have been more apprehensive, more reluctant. Blood still glistened on the playground. No matter how hard they scrubbed, stubborn remnants remained. A skipping rope with which they endeavoured to sweep each other off their feet lay tangled as a noose. A teddy bear lay abandoned, its head flopped to one side, its arms raised apologetically towards the hillside.

For only a fraction of a second, the next victims would hear that very same dull whistle, the tune of death but one single note, a prelude to a crescendo of agonised howls and shrieks, separated by the most peculiar of silences, its length indeterminable or imperceptible, before the blast wave ripped through all in its wake. It was a silence of confusion, of foreboding, where the momentary stillness pleaded to be paused for eternity; to be rewound such that the only whistles were those of the larks in the trees or the children in the park. Henceforth, such sounds become a source of fear, of anxiety, a reminder of horrors foretold.

*Ian Bancroft is a writer based in the former Yugoslavia.

Read the first exctract of the novel "Luka"

To Top

To Top