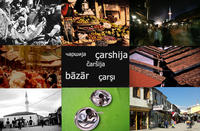

An artisan Baščaršija - foto http://www.bascarsija.info

The ancient Ottoman market is one of the symbols of Sarajevo. This article concludes our series on Balkan bazaars.

Sarajevo finds its expression and its history in the Baščaršija, a quarter in Ottoman style which has proudly survived time and the troubled history of the Balkans. It is the heart of a city which is attracting an increasing number of tourists and seems at last to have erased the signs of the war. Its Ottoman charm begins with its name, derived from the Turkish saraj, palaces, which suggests an urban and refined history. In fact here the Ottoman identity is synonymous with the urban, the historical and the traditional. Neither the war nor demographic developments have succeeded in changing its soul.

The most beautiful of the čaršijas

Its name is Baščaršija which in Turkish means “the main čaršija*”, implying that in the past the city has had others. This one, however, was the most important, situated in the heart of town. Alongside that of Skopje, the Sarajevo carshija is among the largest in the Balkans. It is certainly the most beautiful and refined. From the 1960s it has been a tourist attraction, chosen by the authorities in the Yugoslav period to demonstrate on a small scale the multiethnic character of that Yugoslavia which was Bosnia Erzegovina. But it is also the best example of a typical Ottman bazaar with the quality of a museum, to give an idea of Ottoman history. An exception to the modernizing tendency which characterized most of the town planning in Balkan town after the Second World War.

The survival of Baščaršija was due not only to the inclination of the authorities of the time, but finds its roots in the very identity of the city. The post World War II regimes were only one of the challenges Baščaršija had to face – before that came the Austro-Hungarian government which took control of Bosnia Erzegovina in 1878.

The Austro-Hungarians had planned to replace Baščaršija, its shops, han, cafés, alleys and cobbles with an area planned according to the Mitteleuropean architectural style then in vogue. An idea which met with opposition from the citizens of Sarajevo.

Belonging to that period is the National Library, now under reconstruction, but it is a building which nonetheless fits harmoniously with Baščaršija. Unfortunately it gained fame world wide when in 1994 it was bombed and set on fire with the loss of thousands of manuscripts and objects of the Ottoman, Balkan and Sephardic cultures which were housed there.

Another casualty of that clash between eras was the Inat kuca, a traditional restaurant catering to Ottoman tastes on the bank of the river Miljacka. Knocked down in order to modernize Baščaršija , it was then rebuilt “out of spite” on the opposite side of the river, where it is now.

Ability to adapt

Baščaršija has also been able to survive thanks to its capacity to absorb the new, and adapt to it.: an ability to transform without being destroyed, its evolution over the centuries is now immortalized in its architecture.

Setting off from its old heart where the mosque is located, one encounters the National Library and the oldest brewery in the city, then as one moves in the opposite direction the architectural style progresses as Ottoman shops give way to AustroHungarian buildings which in turn are replaced by the rectangular post war blocks, finishing with shopping centres and present day constructions.

Muslims

Baščaršija is one of the few Balkan čaršijas to have preserved a truly authentic atmosphere. The shopkeepers and craftsmen in the čaršija are all old Sarajevans who have returned after the war to their shops and started to work again just as their ancestors did.

The war has not changed the composition of the čaršija much. Among the blacksmiths in one of the čaršija side streets there is an unusual situation – a woman who, having lost her husband in the war, had to learn his work, that of a blacksmith, to provide for her children.

Most of the shopkeepers are Muslim. Historians say that even before the war most of the shops in the čaršija were run by Muslims. There are also numerous Albanians who mainly run bakeries and cake shops and there are some kebab shops run by more recently arrived Turks.

The number of Serbs can be counted on the fingers of one hand. “I am a Sarajevan, a Bosnian of the Orthodox religion,” says the owner of a shop with the name Blagojević written over its doorway. He declares he never left the čaršija but he refuses categorically to talk about the war years and expresses discomfort at being included in categories in which he does not feel part.

Craftsmen lost and found

As in all the čaršijas, Baščaršija is going through changes, accommodating the dictates of the market. “It is becoming a meeting place, just cafés,” complains an artisan. “When our generation dies off there will be no one left in Baščaršija to do these crafts,” explains the representative of the craftsmen's association, “frankly neither would I push my children to learn a trade which earns little and requires great physical effort.”

But the čaršija shows evidence of new types of craft work. A shop sells articles of clothing hand made by women refugees for whom this job is one of their few means of support. A former theatrical costume designer, on the other hand, creates and sells other articles of clothing, inspired by the styles and settings of the stage.

Tourism, past and future

While even Sarajevo runs the risk of not being spared the effects of commercial tourism and globalization, introducing the principles of responsible tourism could be the way to conserve the authenticity of Baščaršija.

One of the projects developing this idea is part of the Seenet II programme which, in collaboration with local associations like that of the young artisans, 'ZUP,' will open a centre where ancient crafts can be preserved. A school for traditional skills will then be opened, enabling the younger generations to become part of the čaršija, respecting its traditions.

On the lines of the 'ecomuseum / open museum' concept, i.e. a museum structure that enhances and links together objects of daily life, the scenery, architecture and oral testimonies of tradition, the project aims at acquainting visitors with the historical and cultural heritage that they can then look for when going round the town.

"Sarajevo is a city that responds successfully to changes and new ways,” comment Selma Nametak and Daria Antenucci of Oxfam which is promoting the project in Baščaršija through Seenet II, “responsible tourism will give Baščaršija the opportunity to change, keep pace with the times and be appreciated for its authentic identity”.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

To Top

To Top