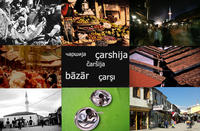

Korça, the bazaar - photo by Marjola Rukaj

Korça is an Albanian town on the borders of Albania, Greece and Macedonia. It is known for its bazaar which unfortunately is now in a semi-abandonned state. This article continues our in-depth analysis of markets with Ottoman origins in the Balkans

History books describe it as one of the most beautiful çarshijas * in the Balkans. In the collective memory of older Albanians it has remained the old Pazar or, more romantically, the Bazaar of the Serenades. In fact it is often associated with the music which for centuries was composed and sung whilst walking with a guitar on the kalldrëm, the round cobblestones, or in the warmth of a han or kafené.

It is situated in the town of Korça, in the history of Albania an important junction from an economic and cultural point of view, thanks mainly to its multicultural nature and openness towards the outside, being on the boundaries between Albania, Greece and Macedonia.

The bazaar even now reflects the variegated cultural composition of the town: its Ottoman inheritance, the harmonious mixture of Albanians, Vlachs, Macedonians and Romani people. With an added touch from the West due to continuous exchanges with Venice, Paris and lands overseas. Right now it just seems like a rough copy of what remains in the recollections of the elderly and in the diaries of travellers who ventured in these parts.

At the edge of the bazaar the asphalt gives way to the kalldrëm, the cobblestones. Men and women hurry through the streets. They seem indifferent to the Ottoman architecture interlaced with the Western style of the early 1900s, to the ancient doors, the town scape which has resisted the waves of time for a good three centuries. The Pazar no longer feels like a place to settle in to spend a few hours chatting, meeting friends and passing some of the day, but just somewhere to dive into the crowd and the garish goods on display, to shop, say hello and hurry away. Can this really be the Bazaar of the Serenades, the heart of the most romantic and advanced town in the country? The answer comes pragmatically from a seller of spices, poor and badly dressed, crushed by the weight of survival: “What are you going to buy?”

The Korça bazaar is now a market, just like many others in Albania: improvised stalls covered with plastic sheeting, markets still called “markets of the refugees”. This term refers to emigrants in the early 90s who, on coming back, often brought Western consumer goods with them to sell. Now it's not like that, but the name has remained.

The shop doors of the old bazaar, to be glimpsed at behind piles of clothes, pans and small electrical appliances, are usually barred. All bazaar activity practically takes place among the stalls. Most shops have been returned to their legitimate owners: those who were able to demonstrate their ownership before the Enver Hoxa regime. But few have decided to invest in them and recover the identity lost during the regime and the long period of transition afterwards.

The only craftsmen left are blacksmiths whom the farmers of the neighbourhood look to for useful tools for an agriculture which is often merely subsistence.

One of the surviving buildings is a han, an ancient Ottoman caravanserai, which has retained part of its original functions. From the entrance neoclassical columns can be seen, built at the end of the 1800s. Modest rooms are still available for two euro per night. “We mostly accommodate illegal immigrants who spend a few days in town, a border crossroads”, says one of the staff in a low voice.

Another han, a building with two floors, with an internal courtyard once used for the horses, a well and several closed commercial structures, has a cafe. The owner belongs to the Ballauri family, one of the most influential in the bazaar. “I try to make a bit of money with the cafe to invest in the rest of the han” he says. The improvements to be made are evident. Like the other buildings in the bazaar, this one has a protection order issued by the superintendent for historical buildings and every intervention must be carefully monitored. Until now the state has, however, only marginally contributed to the recovery of these sites of architectural and cultural value.

During 2010 the Korça bazaar became the subject of a lively debate between the local authorities and a group of architects. The local council had decided to invest approximately 5 million lek, that is 36 thousand euro, to reconstruct the facades of ten or so buildings in the bazaar. “The reconstruction was carried out in just a few days by unskilled bricklayers,” says Maks Velo, a prominent architect and artist originally from Korça. “They totally wrecked the facades, eliminating the original ornamentation and all the elements which distinguish the architecture of the bazaar of Korça from the rest of the Balkans”. For the local authorities what happened is however only a first step: “The bazaar has to be completely rebuilt, but the presence of vendors with their stalls and the Romani people occupying the buildings make it impossible.”

The situation will probably change soon. “Tourism is a priority for the town”, say the local authorities, as they announce that a European grant of ten million euro to revitalize the bazaar is already available. For the time being only part of the project is known: the renovation of the facades and work on the buildings which would enable the traders to exhibit their wares inside.

No-one to date seems to have given any thought to the problem of how to revitalize the crafts tradition in the area. Korça was well known for its metalwork and weaving. With the arrival of communism, the nationalisation of the shops and the planned economy, the craftsmen were brought to their knees. A modernised lifestyle has done the rest.

Neither did Hoxha's regime, in the name of modernization, spare a large part of the architectural structure of the bazaar. Asphalt in many parts took the place of the kalldrëm, wide avenues and buildings of reinforced concrete have in the place of the intimate narrow streets. Of the 700 shops that old people remember, less than 200 remain.

Tourists appear mostly in the summer. They don't stay in Korça, just make a brief stop. Some come from Northern Europe, but most are from the Balkans: Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs, Croats...

Notwithstanding the difficult times, the Korça bazaar is still a meeting place of languages and cultures: Albanian is spoken with varied accents, in one corner a Macedonian is speaking badly in Albanian, the Albanian speaks bad Macedonian, but they talk together, helping each other in turn. In place of the music of the çarshijas and the rhythm beaten out by the tools of craftsmen as they work, the air is filled with traditional songs and people singing them in Albanian, Macedonian, Greek and, some elderly people, in Vlach language.

The Bazaar of the Serenades empties out like all Albanian markets after lunch. Empty, with the stalls packed away, one can see the doors, balconies and shutters which have survived the years. A trip into the past when this was the bazaar of the serenades, a combination of Ottoman çarshija and the Latin Quarter transplanted into what in the 20s was called the Paris of Albania. The middle classes and the more avant-garde intellectuals who lived here had made Paris their point of reference. The serenades played in the cafes of the bazaar are, in many ways, the Albanian version of the chansons of those years, a tradition lasting even now.

The rebuilding work on the bazaar should begin this year. Most probably the facades and shops will retrieve their lost identity. But the real rescue operation would consist in revitalizing the whole bazaar, which will only happen once craftsmen go back to making their kilims (traditional carpets) and souvenirs, painters their pictures; young people will play their guitars at the corners of the alleys and the general population will stroll through it at sunset, stopping in a han to try kernacke, a local dish of minced meat, a Korça beer or a grappa.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

To Top

To Top