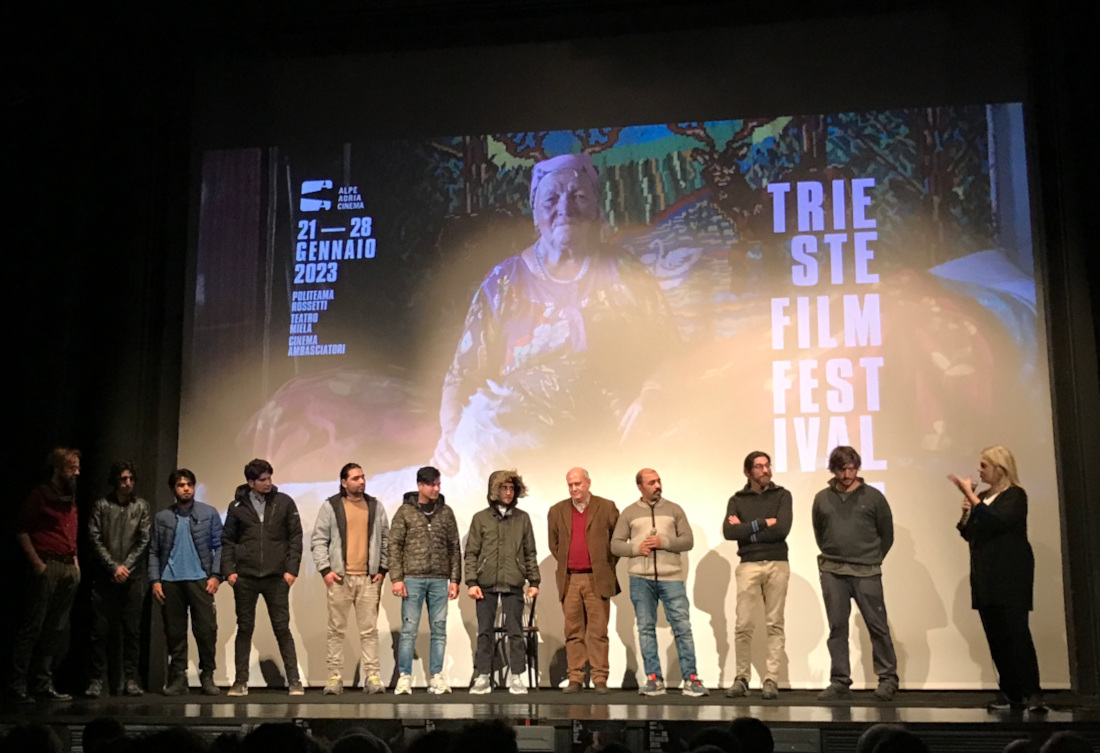

22 January 2022 – Teatro Miela, screening of "Trieste è bella di notte", authors and protagonists on stage (N.Corritore)

In Trieste, the border between Italy and Slovenia crosses the Carso. For some it is a dream territory, for others a nightmare. Interview with Matteo Calore, Stefano Collizzolli, Andrea Segre – the directors of the documentary "Trieste è bella di notte", premiered at the Trieste Film Festival

How did the idea of making this documentary come about?

Andrea: We started doing it before we knew it was going to be a movie. We got a call by Antonio Calò [from Treviso, professor of history and philosophy who welcomed several refugees into his family and was awarded the "European Citizen" award in 2018, ed.], who told us that according to Gianfranco Schiavone, current president of ICS, we absolutely had to make a film on what was happening on the Italian border with Slovenia, i.e. on the "informal readmissions", i.e. on the pushbacks of migrants, implemented by the Italian police. At first I replied that due to lack of time, we couldn't make it. But then they insisted, emphasising that these were important facts. So we left for three days, in spring 2021 in the midst of the pandemic, and we did long interviews with young migrants, in Pashtun and Urdu. Once transcribed and translated, we understood that Calò and Schiavone were right...

How did you come into contact with these migrants? Where did you interview them?

Stefano: It was very easy, thanks to ICS and the RiVolti ai Balcani network that have been working in this area for years. So we inherited both contacts and trust built up over time, as well as mediation with Ismail Swati who then collaborated for ICS Trieste in the making of the film. We also have our own previous history, as producers and authors, of working on these issues.

Matteo: We did the first interviews in Italy, with people who had already arrived in Trieste and applied for international protection. Thanks to ICS Trieste who supported them, we were able to speak with those who had undergone readmission in the past, or at least had witnessed it. In the first phase, the interviews were used to obtain physical testimonies of what had happened, and then deliver them to the civil society actors who file complaints. Then, re-reading the translated transcript, we understood that it made a lot of sense to make a film out of it. Stefano and I decided to go to Bihac, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where had a lot of help from the Border Violence Monitoring Network and Silvia Maraone, who for Ipsia has been working there for some time in assisting refugees and people in transit, as well as others who work on the ground.

Was it your first time in Bosnia or had you already been there in the past?

Andrea: It all started for us in the Balkans years ago, although it seems like the day before yesterday, as you know [Andrea Segre refers to his experiences of the first participatory video workshops in Albania, as an ICS volunteer, ed.] and since then we all grew up inside Zalab which was born right then inside ICS.

Stefano: we needed very little, as the people we had to interview already had a relationship built with the networks present on the ground. So when we arrived at the squat [abandoned ruins used by migrants for shelter, ed.], it was enough to have a word with the migrants and we immediately started recording.

Matteo, you are also director of photography. What difficulties did you find and what strategies did you use in filming in such a place, with little light, uncomfortable conditions, confined spaces?

Matteo: It's actually a typical place we have happened to shoot in the last 15 years, so we know how to deal with the situation. From a purely photographic point of view, those locations always pay off: cooking is done by burning plastic, wood, and other things, so all the walls are blackened and the only light that enters, because there is no electricity, comes from the windows or from the fire. So, my job is just to put the camera in the right spot between the person and the light. We had a bit of difficulty at night, we used about twenty lights and solar panels bought there from a Chinese dealer, which we then gave to the interviewees in case they were needed for the journey (the "Game ").

Photographically, we played a bit with the big bonfires all around the squat, set up by the farmers to preserve the land from real fires in the summer months. Basically they burn the first slice of weeds in the woods, so the fires don't expand and become dangerous. So a surreal atmosphere was created, with flames and smoke enveloping everything inside and outside the squat.

Where did the choice not to use a voice-over come from in editing the documentary?

Andrea: we've hardly ever done it except in two works that are very different from this one. In fact, the voice off, i.e. authorship and the "I", is so much present today that we too have been somewhat influenced by it. But for "Trieste è bella di notte" we immediately reconnected to our choice of many years of work: that is, to try to put our technical expertise at the service of those who really have something to tell, that is the protagonists.

Matteo: Furthermore, one thing we pay close attention to and which is fundamental, but which unfortunately doesn't happen in many documentaries, is to let people speak in their own language while we shoot the images. Even if you don't understand everything, even if it can create difficulties for you when you shoot, it actually allows you to let the speaker manage the story.

Andrea: And it forces you to listen more. Because if you interview in English or in French, or use a mediator in the interviews, you immediately go find what you had in mind. If instead you interview in Pashtun, at the moment you don't understand anything but when you go home you have to translate everything and you have to work much more on that text. And when reading the texts you often understand much more, you find the deepest features of the story.

Stefano: There is also another aspect, in my opinion. While doing the interview you listen in a language you don't know, you are somewhat helpless, but you perceive emotions much more. So you do a first reading on the points where you feel, even if you don't understand the words, that it is something very important for the speaker, and then a second reading on the translated text. This double reading allowed us to go deeper into the interviews, which were already very full in themselves. Moreover, with protagonists who have made themselves available to a very free and intimate story, expressing emotions, fragility…

Matteo: Furthermore, we were lucky to have Ismail Swali, who in fact during the shooting was an assistant director, not just a mediator. Cultural mediator of ICS, he was also one of the students of Zalab's participatory video documentary film school a couple of years ago, so he knows our way of working well. He has huge sensibility and therefore was able to avoid being a "court translator" or a "classic" mediator... these are harmful, because they perhaps translate what the interviewee is saying in a more refined way or they interrupt them, and this destroys your relationship with the narrator.

Andrea: It's a bit like what happens in the commissions that evaluate asylum requests, a disaster – it becomes a narrative in which the interviewee is "crushed" by the interviewer. Instead, Ismail had the ability to stay within the relationship himself. After that, during filming we stopped occasionally, we understood some things, as Stefano has already said, others were explained by Ismail. Sometimes we asked the interviewee questions to better understand. But in any case, Ismail was fundamental, he respected the time of the narration as well as the silences. Chiara Russo was also crucial, she edited everything, in Pashtun and Urdu, without understanding a word... Over the years, working with us, she has developed an incredible ability to edit dialogues in languages she does not speak. She did it with Kazakh, with Bengali, with various African dialects…

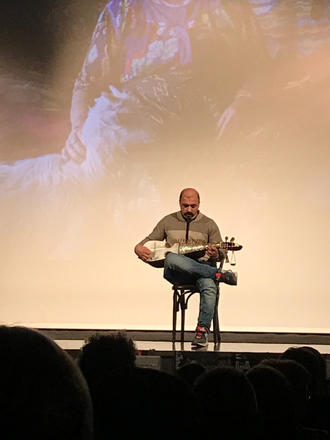

Matteo: Furthermore, an intuition of Ismail's was central. He figured out how to immediately, in a few days, create a relationship of trust with those who lived in the squat. Not bringing the typical humanitarian aid, but something more personal, which allowed them to feel that there was a real sharing of what they had just gone through, because Ismail is also a migrant. He brought his Rabab [lute-like instrument, used by Pashtun tribes, originally from Afghanistan and also used in Pakistan and parts of India, ed.] and therefore Pashtun music as a gift. Inside those walls, where there is no nothing, these moments of music became moments of very strong emotion and sharing, almost liberating.

Can we say that you have brought a moment of normalcy, indeed we could say of "luxury", that is the possibility of playing and singing in such a place?

Stefano: Perhaps also because it is the home instrument, with a strong identity. Their years-long journeys are very bare, out of necessity they travel with nothing of their own. Even the clothes, which you got for example to cross the Croatian mountains, but which don't belong to you. While the rabab belongs to your childhood as well as to your personal future.

From the outset, was there the intention of denouncing the "informal readmissions" perpetrated by the Italian border police towards Slovenia?

Andrea: That was the central starting point. So both to give voice to the human aspect and the experience of these people, and to answer the need for ICS Trieste to collect interviews, material, to be used for campaigns to report violations.

Stefano: Beyond that initial goal, in many of our works we always try to tell a story to say that it's wrong, that the suffering of the journey is pointless and useless. In this documentary there is above all the will to listen to that journey, but it does not pose a thesis, it opens questions. In the sense that with regard to the so-called "informal readmissions" it is not only we, Zalab, ICS or Rivolti ai Balcani who declare their injustice... there is a sentence issued by an Italian state body [see the sentence of the Court of Rome of January 2021, ed.] which decreed its illegality. And that, despite this, Minister Piantedosi recently announced that they will start again. So besides being humanly wrong, it also brings to light strong contradictions.

Andrea: This, moreover, is a dimension that is a little too lacking in humanitarian communication. We are not the first and we will not be the last to address the issue, thank goodness, but few of the films I have seen on the "Game" put the emphasis on political responsibilities, it is not clearly stated where the story that we are telling comes from...

Speaking of political responsibility, in "Trieste is beautiful at night" you also included some institutional voices. Did you have trouble getting them?

Andrea: We encountered enormous difficulties. In the development of the montage we understood that we had to clarify the enigma Stefano talks about, and that is that there is a piece of the state – therefore the Court of Rome – which lists an incredible number of reasons according to which informal readmission is illegal, and another body of the state determined to continue illegally. When we thoroughly read the text of the sentence, with the help of ASGI 's lawyers, we understood the importance of including the interview with judge Silvia Albano who had issued it. Initially she was hesitant, she feared not being able to explain it in a short time and in clear words. In fact she was fantastic: in 3 and a half minutes she manages to summarise a nine-page sentence, in a masterful way.

After this interview it was also necessary to get the position of the Ministry of the Interior. Also because after the sentence it had kept a heavy silence, not even speaking to criticise its content. Indeed, not only did it not make any reaction public, but it even filed an appeal with a ploy: saying that the sentence is not valid because it is not proven that the person who filed the complaint was in Italy...! Obviously it cannot be demonstrated with a document, it was an "informal readmission" therefore without any formal registration procedure.

The negotiation with the ministry was very long, we made the first request in March-April 2022, after silence, we were told a firm no for two months. The affirmative answer came only after we informed that Judge Albano had agreed to be interviewed. The ministry felt the need to respond and chose to let us interview the prefect of Trieste Annunziato Vardè, not Minister Piantedosi directly. We see the result in the documentary... If nothing else, we are the first to whom the ministry has given an official answer.

Where did the choice of the title of the documentary come from?

Andrea: It was born from a very intense scene, in which the interviewee answers a question we asked all of them, in a slightly provocative way, even a little ashamed of it... That is, if there had ever been a happy moment during their journey. Some have replied "What kind of question is that?!" and we agreed with them... But it's actually a question that sought to engage with the elements of energy that are part of making a journey of this kind. There is drama, always, but you also need to have considerable strength of character to pull it off.

The answers that emerge in the film actually help the transfer between the viewer and the interviewee. Because we get not only the one who runs away dressed in "rags", but also the person who experiences moments of joy and happiness...

Andrea: Absolutely. And indeed Daniel, who is an extremely intelligent person, answered the question. At first, listening to him in his language, we understood that he mentioned Trieste. Only later, when Ismail told us the content, did we understand that it could be a crucial point of the documentary.

Stefano: The choice of the title went through many steps, as always happens when making a film. At the beginning it was more linked to the internal contradiction of the Italian state that we were talking about earlier, but also to the European dimension. Because here we are talking about the border with Slovenia, but these are facts that also occur on the border with France, Switzerland, and so on. Finally, we came back to that passage from Daniel. Because it is an important moment in a person's life: the moment in which he sees the lights of Trieste from above at night as soon as he arrives in Italy, as any twenty-year-old could see it, in a normal parenthesis of his life when he goes out for the night.

The central point of this work is pushback. The interviews uncover a strong trauma, which violently adds up to the many others experienced during the journey.

Stefano: Pushbacks are a real trauma for everyone, a more profound trauma than others. In the story it emerges as a hard moment. The protagonists tell of the terrible violence suffered at the hands of the Croatian police during the pushback, which is in itself a trauma. But what emerges above all, and they repeat it several times, is the inexplicability: "Why do they do it? How can a human being behave like this?". Pushback is defined in interviews with words like "the Apocalypse", "hell", "my life was over". Or, "I thought I'd go back… it was better to die", and these two are synonyms, because we are talking about people who fled their country in order not to die.

Here we find a very serious element: a less visible violence than the beatings of the paramilitaries in the Croatian mountains, but more profound because it severs the project, already difficult from the beginning, and in an inexplicable way. For example, one protagonist tells how in the group he was travelling with, some were rejected and some were not, for no explicable reason. For years you have followed a light, the only certainty you have is that once you arrive, rights await you that are guaranteed to you. Why would those who should guarantee you those rights and help you, send you back? Psychologically it's devastating, everything collapses for you.

Stefano: The most beautiful sentence in the film, in my opinion, is when the protagonist talks about the pushbacks and says "For me it was the Apocalypse" and then adds, in light of the arbitrariness of the application of rights, "You may just as well do away with the right of asylum". As if to say, it is better to know that it doesn't exist, at least they don't leave for the journey with the idea that it is possible. Be honest...

You already have an intense calendar of screenings and requests from all over Italy continue to arrive.

Andrea: Yes, and it's a very nice sign. Our wish is for everyone to invite also the protagonists of the documentary, especially Ismail but also the others, some of whom in the meantime have arrived in Italy from Bosnia. It's important to have those who experienced that journey come and talk about it.

Il documentario

The border between Italy and Slovenia is in the hills above Trieste. If you walk through it at night the city lights sparkle in the sea. It may seem like a dream come true. Or the beginning of a nightmare. "Trieste is beautiful at night" is the new film by Matteo Calore, Stefano Collizzolli, Andrea Segre which tells about the readmissions on the border between Italy and Slovenia presented in world premiere on January 22 at the Trieste Film Festival – Alpe Adria Cinema. There are already many dates for the screenings planned throughout Italy, see the continuously updated list on the Zalab website.

Produced by ZaLab Film and Vulcano with the support of Open Society Foundations, in collaboration with the ZaLab Cultural Association and Forum Per Cambiare L'Ordine delle Cose, in collaboration with ICS and Rivolti ai Balcani, with the patronage of Amnesty International and Doctors Without Borders. See the trailer .

Trieste è bella di Notte also supports the RiVolti ai Balcani network. Following the collaboration in the making of the documentary, Zalab decided to donate 30% of the proceeds from online subscriptions to their videos to the network.

To Top

To Top