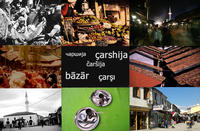

Gjakova/Đakovica - M.Rukaj

Destroyed during the war, the old commercial heart of the town Gjakova/Đakovica, in western Kosovo, was rebuilt in 2001, thanks to international financial contributions. But, suffocated by its traffic, it's struggling to get back to being a “market on a human scale”, typical of the Ottoman period

To get to the social-realist style centre of Gjakova/Đakovica, a town in western Kosovo, the road takes you through the ancient Ottoman market. This road is well kept with traditional paving, but empty of people and congested with traffic. The immediate impression is that the local authorities wanted at all costs to keep the ancient čaršija* alive, but without really knowing how to define it: market, tourist attraction or simply a part of the town keeping its original architecture but left to find its own identity as decided by its development?

Few shops have their shutters open. Some dressmakers, barbers and hairdressers, some carpenters making traditional cradles and coffins and finally a retired chemist, now taxidermist, who stuffs wild animals and walks with the aid of a stick, being a victim of the ever-growing traffic in the çarshija. The vehicles going to and fro towards the centre have taken the upper hand, making the čaršija a long way from a “human scale”, or the pedestrian heart of a town. The traffic even prevents the merchandise from being displayed on the outside window ledges which, according to tradition, should by day become actual stalls propped on the shop windows.

A Han and a Mosque

However, among the low buildings which characterize this part of town, reflecting the architectural principle which would make man the master in the çarshija, some stand out: splendid, on two floors, typical Ottoman structures with white facades, their top floors sticking out, made of carved wood which has both load-bearing and decorative functions.

They are the ancient caravanserai, the so-called Ottoman han. The two oldest, belonging to the Harraqija family, are cited in many historical texts and are the same age as the town. The history of Gjakova/Đakovica in fact began in 1600 with, as in many other Balkan settlements, a mosque and some han for the worshipers and the market. The han, rebuilt strictly in their original style, give a glimpse of what the Ottoman world was in these parts. After sunset when the whole čaršija is enveloped by darkness, the han and their rustic kitchens are the only pulsating place left there.

Reborn from the ashes

At the entrance to the çarshija a marble plaque describes how it was rebuilt in 2001 thanks to a USAID (agency of the United States government) initiative. “It was set on fire on March 24, 1999, leaving only a few crumbling walls, blackened buildings and ashes,” recalls Osman Gojani, an architect who lived through the whole conflict in Kosovo without seeking refuge in Macedonia or Albania.

Čaršijas have left their mark on Osman's life, from that splendid one in Sarajevo where he was born, to the one from which his family originated in Gjakova/Đakovica, now rebuilt, but in need of revitalizing. He has kept all the maps and plans showing the evolution of the çarshija and was involved in designing the latest reconstruction financed by USAID.

“During the war the most treasured things I had were those historical documents which testified to the evolution of the čaršija over time, and my savings. I put them in a plastic folder and buried them in my yard”, he relates. When the conflict was over he got down to work to give his çarshija back its identity. First he set up an association together with the owners of the han, the Harraqija family, then he drew up the plans and continued to monitor the rebuilding. The čaršija had to be rebuilt, not only for reasons of identity for the few citizens who still perceive it as the heart of their town, nor even for tourism, which is finding it hard to achieve lift off in a country like Kosovo, but also because before the war at least 30% of the inhabitants earned their living through activities related to it.

Thus the çarshija was born from its own ashes. Osman Gojani is now a member of a municipal commission which monitors and gives permits to those wishing to rebuild or set up businesses in the čaršija. The aim is to keep as close as possible to its original character. “But sometimes we have to turn a blind eye: there's a widow who's rebuilding her shop. She's poor and needs to work as soon as possible. We can't make her rebuild all over again because she made a mistake rebuilding the stairs or didn't follow the plans inside the building. We try to keep to the traditional form, at least in the facades and in the use of traditional materials in the reconstruction.”

New bureaucrats, old craftsmen

Reconstruction, however, is not enough to revitalize the çarshija. Nor is the association sufficient for its revitalization – some craftsmen criticize it for being passive and lacking strategies in its dialogue with the local authorities. “I'm not in touch with them; they haven't helped me in any way,” says one old craftsman, one of the only ones still making decorated brakes for horses.

Osman Gojani, while admitting to the passivity of the association he is part of, attributes everything to the inadequacy of those occupying important positions in the town: “These are people whose criteria for making decisions do not look to the needs of the town and the development strategies, but rather to pleasing friends, former army comrades and close or distant relatives in their clan.”

“Here's an example,” recounts Ali Haraqija, one of the founders of the association, as he walks down one of the main alleys in the çarshija, showing particular points along the way. “There were lamp posts here where you can still see the sawn-off stumps. They took them away and the čaršija was left in the dark. The local authorities decided to illuminate a nearby village, with those lamps...”

Very Albanian

In the çarshija only Albanian is spoken. Just speaking with an accent from Tirana is enough to set off nationalist solidarity, unrivalled hospitality and craving to talk about Albania, cheap summer holidays and natural beauties that “only Albanians have” and Tirana's unstoppable progress. Only the positive aspects are underlined, a-critically.

Gjakova/Đakovica is very close to the Albanian border and the inhabitants claim this to be the reason for the mono-ethnic composition of their town. “The Serbs were never here”, they always say when asked about non-Albanians who traditionally practised their crafts in the čaršija. “Even if there were some before the war, in reality they were Serbian and Montenegrin colonists brought here to assimilate us. But they didn't succeed ”, says a carpenter amid the cradles and coffins in his workshop. “We never learnt to speak Serbian properly as they did in Peja,” he adds.

But in the çarshija there's no trace even of Rom, Ashkali, Vlachs or others. “No, no, we are only Albanians”, states a passer-by as he tries to explain the Kosovan mono-ethnicity to me. “We are not the way they are in Albania where they distinguish between Tosk, Geg, Çam and a lot of other categories; we here are only Albanians.”

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.