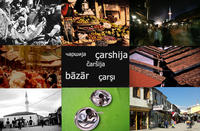

Skopje, the čaršija (Foto Panoramas, Flickr)

A real social and cultural barometer in the heart of Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, this is an ancient Ottoman market which, in the last 20 years, has changed from being a disreputable quarter to a trendy one. Another article in our dossier on Ottoman markets in the Balkans

Ancient Ottoman Capital

Skopje was the seat of a Balkan pasaluk (an Ottoman administrative unit). Its past is still visible in its 'Stara Čaršija', one of the best conserved in the Balkans. Wide streets and neoclassical facades intermingled with the Ottoman architecture are what remains of the old Ottoman capital, a point of contact between Eastern and Western worlds.

The 'Stara Čaršija' is still at the centre of the city, separated from the modern part by the river Vardar and an historical bridge known as the “Stone Bridge”. In the past the bridge connected and separated the mainly Muslim part of town, where the čaršija* is, and the Orthodox one, today dominated by Balkan versions of Mittel European boulevards.

Skopje's çarshija is not like all the others. To understand the state of mind of the Macedonians, Albanians, Turks and all the others who make up Macedonia's rich ethnic composition, you must dive into its narrow streets. It is literally a socio-political barometer, its transformations taking place in step with the changes in Macedonia at large.

The çarshija of the Albanians

Today the local people call it 'Stara Čaršija', the old market, but in the past it used also to be called the Turkish market, since most of the people working there were Muslim. Now experts in jargon call it the 'çarshija of the Albanians'. In fact many people belonging to this community live and work there. The red and black flags and Albanian symbols are to be seen everywhere, as well as the graffiti made by Uçk sympathisers and posters encouraging Albanians to support the struggle for the formation of an ethnic Albania which, according to the nationalists' ambitions, would also include Skopje.

The Albanian community living in the Bazaar is one of the poorest and most traditional in the Balkans. Here Islam is seen as the bulwark of their own identity – the inhabitants often declare themselves first and foremost Muslims. Their speech usually has an accent from the Tetovo mountains or the regions bordering Kosovo; an Albanian accent from Skopje is rare.

They say they have been in the čaršija for over 20 -25 years. In fact they are the leaders of the “albanisation” of the çarshija, following a repeated pattern of ethnicisation of urban spaces in the Balkans. This process began in the 80s while Yugoslavia was sinking into an economic crisis and the economic and social differences between ethnic groups became more and more pronounced, the divisions more visible. The Macedonians left their shops to the new arrivals, moving to the new part of town. The čaršija took on an ethnic character, its main language becoming Albanian and thus losing its multi-ethnic nature. Albanians and Macedonians set up parallel societies, one alongside the other, tolerating but avoiding each other.

In the 90s the Skopje çarshija reached the peak of its isolation. In this period political analysts were betting that Macedonia would end up like Bosnia Erzegovina. As the psychological distance between ethnic groups grew, so did their geographical separation. No Macedonian then passed through the streets of the čaršija which, despite being the cultural and architectural heritage of the city, decayed and was cut off, becoming the disreputable part of town. In the 90s the çarshija was an area to steer clear of, even frequent Albanian visitors from Albania returned from Macedonia with the worst possible impressions. Only some groups of alternative artists made it their meeting place.

From marginal to trendy

Now the situation is changing again, for the better. In the Stara Čaršija Macedonian is heard spoken more frequently. After the handful of alternative artists settled in the area, livening up the cafes with a stimulating atmosphere, the čaršija has become fashionable, moving from alternative to trendy, now quite an attraction in the Macedonian capital and once again patronized. The well known film director Milcho Manchevski shot some promotional films there with the intention of making Macedonia known to a Western public.

There are few craftsmen left, however, doing their own work in the Stara Čaršija: some cobblers, tailors and traditional eating houses. The other shops sell products imported from China or Turkey, not always the best in terms of quality or aesthetics, and most shops are no different from what can be found in any other Balkan capital. If it were not for the Ottoman architecture it would be hard to distinguish the Stara Čaršija from the modern part of town across the Vardar.

It is also difficult to understand how this part of town will fit in the new look Skopje will have in 2014. That is the year when an ambitious and costly project for the architectural and cultural redevelopment of the capital, proposed by the present Gruevski government, will reach completion. At the gates to the çarshija new buildings are already rising, in baroque and neoclassical styles.

The architectural plan conforms entirely to nationalist lines, difficult to reconcile with the heritage of the city both aesthetically and politically, since the urban area of Skopje almost always has a multicultural quality.

Looking for craftsmen

It must nevertheless be said that the čaršija is beginning to find its place in the identity of Skopje's citizens, whatever their nationality or religion. Many NGOs are involved in revitalizing it. In the centre a school for training new craftsmen has been created. The apprentices learning a trade there are all young, come from all the ethnic communities in Macedonia and are, on average, well educated.

In the coming years the potential for tourism in the Stara Čaršija will certainly be appreciated. And maybe, thanks to the new political climate spreading through the Balkans, the divisions between these communities, which have always shared this urban space, will decrease. Now the Albanians and Macedonians in the çarshija are beginning to talk of each other more frequently, remembering how good it was when the čaršija was the point of reference for the city, and when Christmas, Easter and Bajram were occasions for meeting and celebrating together without distinction of nationality or religion.

* To make reading easier the 'bchs' version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.